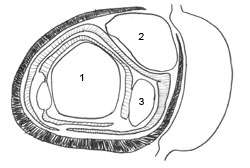

Fig. 1

A cross section of a dormant bud. The three buds within the compound bud can be seen.

BudsA bud contains growing points that develop in the leaf axil, the area

just above the point of connection between the petiole and shoot. The

single bud that develops in this area is described in botanical terms

as an axillary bud. It is important to understand that a bud develops

in every leaf axil on grapevines, including the inconspicuous basal

bracts (scale-like leaves). In viticulture terminology, we describe the

two buds associated with a leaf – the lateral bud and the dormant bud

(or latent bud). The lateral bud is the true axillary bud of the

foliage leaf, and the dormant bud forms in the bract axil of the

lateral bud. Because of their developmental association, the two buds

are situated side-by-side in the main leaf axil.

Although the

dormant bud (sometimes called an “eye”) looks like a simple structure,

it is actually a compound bud consisting of three growing points,

sometimes referred to as the primary, secondary, and tertiary buds

within one bud. The distinction between secondary and tertiary buds is

sometimes difficult to make when observing the bud visually and is

often of little importance, so it is common to refer to both of the

smaller buds as secondary buds. These three buds are packaged together

within a group of external protective bud scales within the compound

bud. As the bud develops, it follows the pattern of nomenclature as the

buds on the shoot: the primary growing point is the axillary bud of the

lateral bud; the secondary and tertiary growing points are the axillary

buds of the first two bracts of the primary growing point.

The

dormant bud is the focal point during dormant pruning, since it

contains cluster primordia (the fruit-producing potential for the next

season). It is called dormant to reflect the fact that it does not

normally grow out in the same season in which it develops.

The

dormant bud initiates the year prior to its growthGrapeExtOrg3.jpg as a shoot. During

that prior season, it undergoes considerable development. The three

growing points of the compound bud each produce a rudimentary shoot

that ultimately will contain primordia (organs in their earliest stages

of development) of the same basic components that comprise the current

season’s fully grown shoot: leaves, tendrils, and in some cases flower

clusters. The primary bud develops first; therefore it is the largest

and most fully developed by the time the bud goes dormant. If it is

produced under favorable environmental and growing conditions, it will

contain flower cluster primordia before the end of the growing season.

The flower cluster primordia thus represent the fruiting potential of

the bud in the following season. Reflecting the sequence of

development, the secondary and tertiary buds are progressively smaller

and less developed. They generally will be less fruitful (have fewer

and smaller clusters) than the primary bud. Bud fruitfulness (potential

to produce fruit) is a function of the variety, environmental

conditions, and vineyard production practices. Dormant buds that

develop under unfavorable conditions (shade of a dense canopy, poor

nutrition, etc.) produce fewer flower cluster primordia for the

following season.

In most cases, only the primary bud grows, producing the primary

shoot in the following season. The secondary bud can be thought of as a

“backup system” for the vine; normally, it grows only when the primary

bud or young shoot has been damaged, oftentimes from freeze or frost in

spring. However, under some conditions such as severe pruning,

destruction of part of the vine, or boron deficiency, it is possible

for two or all three of the buds to produce shoots in spring (Winkler

et al., 1974). Tertiary buds provide additional backup if both the

primary and secondary buds are damaged, but they usually have no flower

clusters and thus no fruit. If only the primary shoot grows, the

secondary and tertiary buds remain alive, but dormant at the base of

the shoot.

The lateral bud will grow in the current season, but

growth may either cease soon after formation of the basal bract or it

can continue, producing a lateral shoot (summer lateral) of variable

length. Regardless of the extent of lateral bud development, a compound

bud develops in the basal bract, forming the dormant bud. Long lateral

shoots sometimes produce flower clusters and fruit, which is known as

"second crop." However, because these develop later in the season than

fruit on the primary shoot, “second crop” fruit does not fully mature

in many areas of the country. If a lateral bud does not grow in the

current season, it will die.

Flowers and FruitA

fruitful shoot will usually produce one to three flower clusters

(inflorescences) depending on variety. Flower clusters develop opposite

the leaves typically at the third to sixth nodes from the base of the

shoot, depending on the variety. If three flower clusters develop, two

develop on adjacent nodes, the next node has none, and the following

node has the third flower cluster. The number of flower clusters on a

shoot is dependent upon the grape variety and the conditions of the

previous season under which the dormant bud (that produced the primary

shoot) developed. A cluster may contain several to many hundreds of

individual flowers, depending on variety.

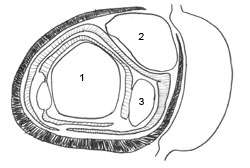

Fig. 2

Grape

buds and flowers.

A compound bud with primary, secondary, and tertiary

buds (T),

and flowers from formation to cap fall to pre-fertilization.

The

grape flower does not have conspicuous petals, instead, the petals are

fused into a green structure termed the calyptra, but commonly referred

to as the cap. The cap encloses the reproductive organs and other

tissues within the flower. A flower consists of a single pistil (female

organ) and five stamens, each tipped with an anther (male organ). The

pistil is roughly conical in shape, with the base disproportionately

larger than the top, and the tip (called the stigma) slightly flared.

The broad base of the pistil is the ovary, and it consists of two

internal compartments, each having two ovules containing an embryo sac

with a single egg. The anthers produce many yellow pollen grains, which

contain the sperm. Wild grapevines, rootstocks (and a few cultivated

varieties such as St. Pepin) have either pistillate (female) or

staminate male flowers -- that is, the entire vine is either male or

female. Vines with female, pistillate flowers need nearby vines with

staminate or perfect flowers to produce fruit. The majority of

commercial grapevine varieties have perfect flowers, that is, both male

and female components.

Fig. 3

An individual grape flower is shown with floral parts labeled

Stages of BloomWhen

the individual flowers on a grape inflorescence open, it looks

different than the bloom of most flowers. The cap separates from the

base of the flower, becomes dislodged and usually falls off, exposing

the pistil and anthers. The anthers may release their pollen either

before or after cap fall. Pollen grains randomly land upon the stigma

of the pistil, allowing pollination. Multiple pollen grains can

germinate, each growing a pollen tube down the pistil to the ovary and

entering an ovule, where a sperm unites with an egg to form an embryo.

The successful union is termed fertilization, and the subsequent growth

of berries is called "fruit set." The berry develops from the tissues

of the pistil, primarily the ovary. The ovule together with its

enclosed embryo develops into the seed.

Fig. 4

A grape inflorescence with nearly 100% cap fall

Because

there are four ovules per flower, there is a maximum potential of four

seeds per berry. Unfavorable environmental conditions during bloom such

as cool, rainy weather can reduce fruit set (number of berries) and

seeds per berry, thereby affecting berry size. Berry size is related to

the number of seeds within the berry, and very few seeds leads to

smaller berries. However, berry size can also be influenced by

environmental conditions, management practices, and water management.

Some immature berries may be retained by a cluster without completing

their normal growth and development, a phenomenon known as “ coulure”

or “hens and chicks” (Mullins et al., 1992).

Reviewed by Tim Martinson, Cornell University and Patty Skinkis, Oregon State University

References:Mullins, M. G., A. Bouquet, and L. E. Williams. 1992. Biology of the Grapevine. Cambridge University Press.