The Date

"Honor your

maternal aunt, the

palm," said the prophet Muhammad to the Muslims; " for it was created

from the clay left over after the creation of Adam (on whom be peace

and the blessings of God!)." And again, "There is among the trees one

which is preeminently blessed, as is the Muslim among men; it is the

palm."

It is in this reverential aspect that the Semitic world

has always regarded the date palm; and with sound reason, for its

economic importance to the desert dweller as the source of both food

and shelter is even greater than that of the coconut palm to the

Polynesian. Only in recent years, however, have oriental methods of

date-culture been scientifically examined and tested by

horticulturists. By far the greater part of this work must be credited

to investigators in the United States.

The first modern

importation to this country was of palms rooted in tubs, shipped from

Egypt to California in 1890. Better methods of shipping offshoots were

gradually worked out, and introductions from all parts of the world

have been made in ever increasing numbers in the last quarter of a

century. Meanwhile, continued study has been given to methods of

culture, with the result that the problems of the rooting of offshoots

and the ripening of the fruit, which were at first serious sources of

loss, have been brilliantly solved, and many others adequately dealt

with. This work has been done by the United States Department of

Agriculture, the experiment stations of California and Arizona, and

many private growers; and any history of the progress of scientific

date-culture will certainly record the names of such pioneers as Bruce

Drummond, David Fairchild, R. H. Forbes, George E. Freeman, Bernard

Johnston, Fred N. Johnson, Thomas H. Kearney, Silas C. Mason, James H,

Northrop, F. O. Popenoe, Paul Popenoe, Walter T. Swingle, and A. E.

Vinson.

As a result of the work not only of the Americans but of

French horticulturists in North Africa and English in Egypt and India,

the culture of the date palm is to-day perhaps better understood than

that of any other fruit of which this volume treats. There is room,

however, for immense improvement in method in practically all of the

older date-growing regions, and the introduction of more scientific

culture will add greatly to the national wealth in many parts of the

Orient.

Such an important date-growing country as Egypt

does not now produce enough dates for its own consumption; for although

it is a moderate exporter it is still more of an importer of low-grade

dates from the Persian Gulf. The markets of North America and Europe

have scarcely been touched. Before the Great War the annual importation

into New York was thirty to forty million pounds, only five or six

ounces a head of the country's population. This is a ridiculously low

rate of consumption for a fruit possessing the food-value of the date,

and which can be produced so cheaply. There would seem to be no reason

why it should not become an integral part of the diet of American

families, being eaten not as a dessert or luxury only, but as a source

of nourishment. So regarded the market is almost unlimited, and

considering how few are the areas available for growing first-class

dates, over-production seems hardly possible.

The date palm

characteristically consists of a single stem with a cluster of

offshoots at the base and a stiff crown of pinnate leaves at the top.

It reaches a maximum height of about 100 feet. If the offshoots are

allowed to grow, the palm eventually becomes a large clump with a

single base.

The plant is dioecious in character, i.e.,

staminate and pistillate, or male and female, flowers are produced by

separate individuals. The inflorescence is of the same general

character in both sexes, a long stout spathe which bursts and discloses

many thickly crowded branchlets. Upon these are the small, waxy-white,

pollen-bearing male flowers, or the greenish female blossoms in

clusters of three. After pollination, two out of each three of the

latter usually drop, leaving only one to proceed to maturity. Chance

development of a blossom that has not been pollinated occasionally

gives rise to unfounded rumors of the discovery of seedless dates;

genuine seedless varieties have, however, been credibly reported.

The

fruit varies in shape from round to long and slender, and in length

from 1 to 3 inches. While immature it is hard and green; as it ripens

it turns yellow, or, in some varieties, red. The flesh of the ripe

fruit is soft and sirupy in some varieties, dry and hard in others. In

many kinds, including most of those that ripen early, the sugar-content

never attains sufficient concentration to prevent fermentation; the

fruit of such varieties must, therefore, be eaten while fresh.

In cultivation about 90 per cent of the male palms are usually

destroyed, since they can bear no fruit.

The presence of offshoots around the base is one of the simplest ways

to distinguish the date palm, botanically known as Phoenix dactylifera,

L., from the wild palm of India (Phoenix

sylvestris, Roxb.) and the Canary Island palm (P. canariensis,

Hort.); from the latter, which is often grown in the United States for

ornamental purposes, it may also be distinguished by its more slender

trunk, and by its leaves being glaucous instead of bright green.

Phoenix

dactylifera is commonly supposed, following

the study of O. Beccari,1

to be a native of western India or the Persian Gulf region. Evidently,

long before the dawn of history, it was at home in Arabia, where the

Semites seem to have accorded it religious honors because of its

important place in their food supply, its dioecious character, and the

intoxicating drink which was manufactured from its sap, and which in

the cuneiform inscriptions is called "the drink of life."

Traditions

indicate that when the Semites invaded Babylonia they found in that

country their old friend the date palm, particularly at Eridu, the Ur

of the Chaldees (Mughayr of modern maps) whence Abram set out on his

migration to Palestine. It is even suggested that the Semitic

immigrants settled at Eridu, which was then a seaport, on account of

the presence of the date palms, one of which was for many centuries a

famous oracle-tree. Several competent orientalists see in the date palm

of Eridu the origin of the Biblical legend of the Garden of Eden.

In

very early times the palm had become naturalized in northern India,

northern Africa, and southern Spain. From Spain it was brought to

America a few centuries ago.

In the last quarter of a century,

United States governmental and private investigators have visited most

of the date-growing regions of the Old World in search of varieties for

introduction into this country, where, in California and Arizona, may

now be found assembled all the finest ones that cultivation, ancient

and modern, has yet produced.

Orthodox Muslims consider that the

dates of al-Madinah, in Arabia, are the best in the world, partly for

the reason that this was the home of the prophet Muhammad, who was

himself a connoisseur of the fruit. Unbiased judgment, however,

commonly yields the palm to the district of Hasa, in eastern Arabia,

where the delicious variety Khalaseh grows, watered by hot springs. The

district of greatest commercial importance is that centering at Basrah,

on the conjoined Tigris and Euphrates rivers, a region which contains

not less than 8,000,000 palms and supplies most of the American market.

The region around Baghdad, while less important

commercially, contains a larger number of good varieties than any other

locality known. Date cultivation by Arabs is most scientifically

carried on in the Samail Valley of Oman (eastern Arabia), where alone

the Fardh dates of commerce are produced. Serious attempts to put the

date industry of northwestern India on a sound basis are being made,

and with good prospects of success. Western Persia and Baluchistan

produce some poor dates and incidentally a few good ones.

In

Egypt there are nearly 10,000,000 palms, of which seventenths are

widely scattered over Upper Egypt. Most of them are seedlings and

practically all are of the "dry" varieties. On the whole, the Egyptian

sorts are inferior.

The Saharan oases of Tripoli, Tunisia, and

Algeria contain many varieties, of which one (Deglet Nur) is as good as

any in the world, and is largely exported not only to Europe but to the

United States, where it is marketed under the name of "Dattes

Muscades du Sahara." Morocco grows good dates in the Tafila let oases

only, whence the huge fruits of one variety (Majhul) are shipped to

Spain, England, and other countries. The date palms of southern Spain

are seedlings and bear inferior fruit. Elsewhere about the

Mediterranean the palm is grown mainly as an ornamental plant.

Intelligent

culture of the date palm is now being attempted in some of the dry

parts of Brazil, where it promises to attain commercial importance. It

is doubtful whether the date will succeed commercially in any moist

tropical region, although in isolated instances successful ripening of

fruit has been reported in southern India, Dominica (British West

Indies), Zanzibar, and southern Florida.

A large area in

northern Mexico, not yet developed, is undoubtedly adapted to this

culture; but experimental attempts with it on the Rio Grande in Texas

have been abandoned. Arizona and California offer the best fields for

date growing in the United States, and in the Coachella Valley of

California (a part of the Colorado River basin) conditions are

particularly favorable. Residents of this valley are not exceeding the

truth in asserting it to be the center of scientific date-growing at

the present time.

Dates consist mainly of sugar, cellulose, and

water. An average sample of fruits on the American market will show in

percentages:1 carbohydrates 70.6 per cent,

protein 1 .9 per

cent, fat 2.5 per cent, water 13.8 per cent, ash (mineral salts) 1.2

per cent, and refuse (fiber) 10.0 per cent. Cane-sugar is found in

dates; in a few varieties this is partly or wholly inverted by the time

the fruit is fully ripe.

A diet of dates is obviously rich

in carbohydrates but lacking in fats and proteins. It is, therefore, by

no accident that the Arabs have come to eat them habitually with some

form of milk. This combination makes an almost ideal diet, and some

tribes of Arabs subsist on nothing but dates and milk for months at a

time.

By Arabs, as well as by Europeans, the date is commonly

eaten uncooked. Unsalted butter, clotted cream, or sour milk is thought

to "bring out the flavor" and render the sugar less cloying. The

commonest way of cooking dates is by frying them, chopped, in butter.

For

native consumption around the Persian Gulf and in India, immature dates

are boiled and then fried in oil. Jellies and jams are made from dates,

and the fruit is also preserved whole. Again, they may be pounded into

a paste with locusts (grasshoppers) and various other foodstuffs. The

soft kinds are tightly packed into skins or tins, when they are easily

transported and will keep indefinitely.

Various beverages are

made by pouring milk or water over macerated dates and letting slight

fermentation take place. The sap of the plant provides a mild drink

resembling coconut milk, which when fermented becomes intoxicating.

From cull dates a strongly alcoholic liquor is distilled, which,

flavored with licorice or other aromatics, becomes the famous (or

rather perhaps, infamous) arrak, of which many subsequent travelers

have confirmed the verdict of the sixteenth-century voyager Pedro

Teixeira, himself probably no strict water-drinker, who said of it,

"This is the strongest and most dreadful drink that was ever invented,

for all of which it finds some notable drinkers."

Cultivation

While

the date palm grows luxuriantly in a wide range of warm climates, it

is, for commercial cultivation, adapted only to regions marked by high

temperature combined with low humidity. Properly speaking, it belongs

to the arid subtropical zone. A heavy freeze will kill back the leaves,

but the plant may nevertheless be as healthy as ever in a year or two.

Thus, date palms have withstood a temperature of only 5° above zero and

have borne satisfactory crops in subsequent years. Ellsworth Huntington

speaks of seeing the date palm in Persia where twenty inches of snow

lay on the ground; many generations of natural selection in such an

environment would doubtless produce a hardy race, but such a region

would scarcely be thought adapted to commercial date-growing.

At

the other climatic extreme, the date palm apparently finds no limit,

being at its best where the summer temperature stays about 100° for

days and nights together. The combination of warm days with cool nights

is unsatisfactory; unless there is a prolonged season during which high

temperatures prevail night and day, the best varieties of dates will

not ripen successfully.

Humidity is an important factor

with many varieties. Dates coming from the Sahara usually demand a dry

climate; yet the Coachella Valley in California has sometimes proved

too dry, and the fruit has shriveled on the tree unless irrigation was

given while it was ripening. Persian Gulf and Egyptian varieties will

endure more humidity, since they come from the seacoast or near it. Dew

at night or rain coming late in the season when the dates are softening

is almost ruinous to the crop, for which reason dates cannot be

produced satisfactorily in some parts of Arizona. In regions of India

where the summer rains begin in July, it has been possible to bring

dates to maturity before the rains arrive.

In general, the best

varieties require: (1) a long summer, hot at night as well as in the

daytime; (2) a mild winter, with no more than an occasional frost; (3)

absence of rain in spring when the fruit is setting; and (4) absence of

rain or dew in the fall when the fruit is ripening. In regions lacking

any of these characteristics, date-growing will be profitable

commercially only if special care is taken to secure suitable varieties

and to develop, by experiment, proper methods of handling them.

Date

palms grow well in the stiff clays of the Tigris-Euphrates delta, in

the adobe soils of Egypt, in the sand of Algeria, and in the sandy loam

of Oman and of California. No one type of soil can be asserted to be

necessary. Thorough drainage and aeration of the soil are desirable,

but even in these regards the palm will stand considerable abuse, and

is found to grow fairly well in places where the ground-water level is

comparatively near the surface. Naturally, however, the palm responds

to good treatment as do other plants. On the whole, it is probably best

suited on a well-drained sandy loam.

The palm's tolerance of

alkali has been noted from very early times, and has led Arab writers

to believe that it throve best in alkaline soil. This is unlikely.

Dates can indeed be grown successfully in ground the surface of which

is white with alkaline efflorescence, provided the lower soil reached

by the roots is less salty; but it is probable that the limit of

tolerance is somewhere about 3 per cent of alkalinity, and the grower

who looks for the best results should not plant on soil whose total

alkaline content exceeds one-half of 1 per cent. Naturally, old date

palms will stand more alkali than young ones. It should be noted that

the so-called black alkali, consisting of carbonates of sodium and

potassium, is more harmful than the more or less neutral chlorids,

sulfates, and nitrates of sodium, potassium, and magnesium which go by

the name of white alkali.

If the irrigating water is free from

alkalinity, it will, of course, help to counteract any alkali present

in the soil; whereas the grower who needs to irrigate with brackish

water must plant his palms in fairly alkali-free soil. Desert

landowners sometimes calculate that soil which is too salty for

anything else is good enough for a date plantation. This is

short-sighted reasoning. Date-growing is, when rightly conducted, so

profitable that it is worth giving the best conditions available, and

the wise grower will plant his palms in his best soil. The ground

should be tested to a depth of six or eight feet to determine its

alkali-content, particularly if there is salt evident on the surface.

Unless at least one stratum of alkali-free soil is found not far from

the surface, the ground should not be used for date palms.

It is

the custom in the United States to plant date palms 50 to the acre. The

grower with plenty of land may find that 40 to the acre (33 feet apart

each way) is more convenient. Arabs plant them much closer but do not

cultivate their plantations frequently. The question of spacing is

affected both by the nature of the soil and by the variety planted;

according to Bruce Drummond, such kinds as Saidi and Thuri give the

best results if spaced 35 or 38 feet apart.

Drummond gives the following advice about planting:

"The

rooted offshoot when ready for transplanting should be pruned from

three to five days before removing from the frame. The new growth

should be cut back to one-half the original height, leaving from three

to five leaf stubs to support the expanded crown of leaves. The holes

in the field should be 3 ft. in diameter and 3 ft. deep, with from 12

to 16 in. of stable manure placed in the bottom of each, with 6 in. of

soil on top, then irrigate thoroughly. The rooted palm when removed

from the nursery should carry a ball of earth large enough to protect

the small fibrous roots from exposure to the sun or dry winds. The

average depth for planting should be 16 in., but this may be varied

somewhat with the size of the shoot. In any case, the depth should be

as great as can be without danger of covering the bud."

"It is not

advisable to transplant rooted offshoots later than June. April and May

are considered the best months of the entire year for the transplanting

of either young or old date palms."

"In southern California, where

the dry winds occur from March to June, the transplanted palms should

be irrigated thoroughly every week; in sandy soil two irrigations a

week should be given until new strong growth is established."

Arabs

usually follow the basin method of irrigation, and it has been

satisfactory in many other parts of the world. The most skillful

American growers who irrigate in basins make them 15 feet square and a

foot deep, filling them with a loose mulch of straw or stable manure.

Most

American growers, however, prefer to irrigate in furrows, and use no

mulch. The function of the mulch in reducing evaporation is covered by

giving a thorough cultivation with a surface cultivator or

spring-toothed harrow as soon as the ground has dried out enough to be

workable. This involves cultivation of the ground every week or two.

Adequate

fertilization of the soil is absolutely necessary in order to make date

palms produce fruit as heavily as commercial growers desire and at the

same time yield well in offshoots. Nitrogen-gathering cover-crops are

much in favor, sesbania or alfalfa being preferred in California. The

long roots of the latter are useful to break up any hardpan or layer of

hard silt which may be present. Many growers plant garden-truck between

the rows of palms, especially while the latter are young and making no

financial return.

The soil in which date palms are usually grown

is of a kind that benefits by the incorporation of rough material, and

stable manure is, therefore, the fertilizer of first choice.

Wheat-straw or similar loose stuff is frequently added with advantage.

An annual application of fertilizer is required in most localities, and

if the soil is sandy the grower must be more liberal. For palms

producing offshoots, half a cubic yard a year is advised; for older

palms a full yard is desirable: both in addition to such cover-crop as

the grower may select.

In regard to irrigation, it is to

be borne in mind that the soil must be kept moist during the entire

year, and that the roots of the palm go deep. The character of the soil

must be carefully and experimentally studied before the grower can be

certain that he has arrived at the correct method for irrigation. The

amount of water that the palm can stand in well-drained land is

strikingly illustrated in the great plantings around Basrah, where

fresh water is backed into the gardens by tidal flow, so that there are

two automatic irrigations each day throughout the year.

In the Coachella Valley, with furrow irrigation, a twentyfour-hour flow

each twelve days from April to November has generally been

satisfactory, although in many soils weekly irrigation is required.

During the winter the rainfall usually suffices. Each application of

fertilizer must be followed promptly by several irrigations.

Pruning

is not so important with date palms as with many fruit-trees. Dead

leaves should be removed from young palms, and if the top growth is

heavy the two lower rows of leaves may be removed when the palm is four

years old. Regular pruning should begin about the sixth year, after

which one row of leaves is usually removed at each midwinter. Drummond

advises that "the leaves should not be pruned higher than the

fruit stems of the former crop, which will leave about four

rows

of leaves below the new fruit stems, or approximately 30 to 36 expanded

leaves."

Propagation

The

date palm can be propagated in only two ways: by seed, and by the

offshoots or suckers which spring up around the base or sometimes on

the stem of the palm until it attains an age of ten to twenty years.

Seedlings

are easily grown, but offer little promise to the commercial grower.

Half of the plants will be males, and among the females there will be

such a wide variation that no uniformity of pack or quality can be

secured. In regions with a large proportion of seedling palms, such as

Spain and parts of Egypt, there is practically no commercial

date-culture. Most growers in California plant a few seedlings for

windbreak or ornamental purposes. These yield a supply of males, but

males can be secured better by growing offshoots from male palms of

known value.

The multiplication of the date palm, therefore, is

reduced in practice to the propagation of offshoots, and skill or lack

thereof in this regard will determine largely the grower's success or

failure at the outset.

In California at the present time the

yield of offshoots is almost as valuable as that of fruit, and growers,

therefore, desire to secure as many offshoots of their best varieties

as possible. For this purpose ample fertilization and irrigation must

be supplied. After the fourth or fifth year of a palm's life, the owner

can usually take at least two offshoots a year from it for a period of

ten years. The best size for offshoots at removal is when they weigh

from ten to fifteen pounds (say 5 to 6 inches, is greatest diameter).

The best season for the purpose is during February, March, or April.

Four

or five days before the offshoots are to be removed from the

mother-palm, their inner leaves should be cut back one-half and the

outer leaves two-thirds of their length. It will be well worth while to

have a special chisel made for removing offshoots. It should have a

cutting bit of the best tool steel, 5 inches wide by 7 inches long, one

side flat, the reverse beveled for 2 inches on the sides as well as on

the cutting edge. The chisel should have a handle of soft iron 3 feet

long and 1-j inches in diameter, such as can be hammered with a

sledgehammer. The delicate operation of cutting is described by Bruce

Drummond, who is the best American authority on the culture of the

palm, as follows:

"To cut the offshoots from the tree the flat

side of the chisel should always be facing the offshoot to be cut. Set

the chisel well to the side of the base of the offshoot close to the

main trunk. Drive it in with a sledge until below the point of union

with the parent trunk; then by manipulating the handle the chisel is

easily loosened and cuts its way out. Next reverse and cut from the

opposite side of the shoot until the two cuts come together. This

operation will in most cases sever the offshoot from the trunk. No

attempt to pry the offshoot from the tree should be made, as the

tissues are so brittle that the terminal bud may be ruined by checking

or cracking. In cutting offshoots directly at the base of the palm the

soil should be dug away until the base of the offshoot is located and

enough exposed to show the point of union with the mother plant. Then

the chisel can be set without danger of cutting the roots of the parent

tree so much as to injure or retard its growth. The connection of the

offshoot on such varieties as Deglet Nur is very small, and there is no

necessity of cutting deeply into the trunk to sever the offshoot from

the tree."

Once separated from its parent, the moist offshoot

requires a period of seasoning before it is dry enough to be planted

without danger of fermentation. Offshoots from the base of a palm are

usually softer and sappier than those growing some distance above

ground. The evaporation should amount to 12 or 15 per cent of the total

weight, which will require at least ten to fifteen days to effect.

Offshoots are usually left where cut, on the ground beneath the palm,

to season.

The Arabs plant offshoots at once in their permanent

locations in the orchard, but the best results will be obtained by

first rooting the young plants in a shed or frame where the two

necessary conditions of high temperature and high humidity can be

maintained. In California this is often done cooperatively.

A

common type of shed for an individual grower is 12 by 20 feet in size

with side walls 6 and 7 feet high respectively, presenting a roof-slope

to the sun. The sides are usually of boards covered with tarred paper

and the roof of 8- or 10-ounce canvas. In such a shed on an ordinary

California summer day, the temperature will be about 115° and the

humidity should be about 75.

The soil inside the shed should be

a light sandy loam, well drained. Ten inches of the top soil should be

removed and replaced with fresh stable manure, well packed, on which 2

inches of soil should be replaced. After a thorough flooding, the bed

should be allowed to steam for a week, and then be flooded again,

whereupon it is ready for the offshoots. These should be planted about

8 inches deep; in any case the bud must be above danger of flooding.

During the summer the bed must be flooded at least twice a week, to

keep the humidity at as high a point as possible. The offshoots must be

kept in it until they are thoroughly rooted and have half a dozen new

leaves. This may require one year or may need several years.

The causes that may lead to failure with offshoots are summarized by

Drummond as:

"(1)

improper selection of the location for the nursery bed; (2) failure to

construct the frame so nearly air-tight as to insure the necessary

humidity and high temperature; (3) improper methods of cutting and

pruning, and the neglect of seasoning before planting in the

nursery-bed; and (4) the neglect of irrigation when necessary and

failure to apply water properly. The points above mentioned are all

essential to success, and to neglect one and observe the others may

lead to as great a failure as to neglect them all." On the other hand,

by using the proper care growers frequently succeed in making 90 to 95

per cent of their offshoots take root.

After they are removed to

the open field, the young palms should be protected by wrapping during

the following winter from the possibility of freezing, as they are

tender at first. Newspaper is as good as anything for the purpose;

canvas, burlap, and palm-leaves are also used.

For security, the

orchardist should allow one or two male date palms for each acre of

fruit bearing trees. Care should be taken to secure males that flower

early in the season and yield abundant fertile pollen; sterility is

common.

|

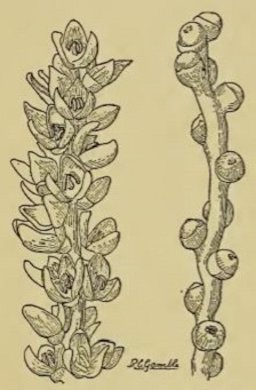

Fig. 28.

On the left, a sprig of staminate or pollen-bearing flowers of the date

palm; on the right, pistillate flowers which will, if properly

pollinated, develop into fruits. |

The

female palm ordinarily blossoms between February and June (in

California usually during March and April). Flowers appearing later

than May 1 are not worth pollinating, so far as commercial production

is concerned. Artificial pollination has been practiced since the dawn

of history, and offers no difficulties.

The flowers of the two

sexes can be distinguished readily (Fig. 28). The branchlets of the

male inflorescence are only about 6 inches long, and are densely

clustered at the end of the axis, while those of the female are several

times as long and less densely clustered. The male blossoms are waxy

white in color, the female more yellowish; while also the latter are

much the less closely crowded together on the branchlets.

The presence of pollen in the male flower is in most cases easily to be

detected by shaking a cluster of the blossoms.

As

soon as the spathe containing the pollen-bearing flowers opens, it

should be cut and put into a large paper bag to dry, the bag being

stored, open, in a dry room. Thoroughly dry pollen will retain its

vitality for many years, and a small quantity should be kept in a

bottle from year to year, as a precaution. In case of need it can be

used with a wad of cotton.

The pistillate flowers should be

pollinated as soon as the spathes crack open, the plantation being

inspected every day or two with this in view. The operation is

preferably carried out about midday. The split female spathe is held

open, and a sprig from the male flower gently shaken over it and then

tied, open flowers downward, at the top of the female cluster. A single

pollination with one sprig is enough for each cluster unless rain

follows within twenty-four hours, in which case the operation should be

repeated. The grower should keep the situation well in hand.

The

grower must not let his young palms bear too many dates, particularly

if he wants them to produce offshoots at the same time. Part of the

female spadices (flower-stalks) should, therefore, be cut off. In most

cases a palm may be allowed to bear its first two bunches of fruit in

its fourth year, and three or four bunches in each of the next two

years. If even a fullgrown palm is allowed to bear to its limit in any

year, it is likely to bear less the following season.

In case

the grower should find himself absolutely without date pollen at a time

when his pistillate trees are flowering, he may have recourse to the

pollen of some other Phoenix,

or even of a different genus of palms, Chamserops, Washingtonia, or

whatever it may be. This will often enable him to save part, if not

all, of the crop.

Yield and

Season

Most

varieties of date palm, if properly cared for, will begin to bear in

the fourth year, and should yield a considerable return in the fifth

and succeeding years. Under Arab treatment they usually take longer.

References in the Code of Hammurabi (about 2000 B.C.) indicate that the

Babylonians at that time could secure a paying crop in the fourth year;

if so, they were better cultivators than their modern descendants.

Beginning

with two small bunches, the grower may allow his palms to bear an

increasing amount each year until maximum is reached. After the fifth,

sixth, or seventh year, 100 pounds or thereabouts to a tree can be

maintained steadily without difficulty by most varieties, and one or

two offshoots a year will still be produced, given proper fertilization

and irrigation. In many cases even larger yields can be obtained. If,

however, the growing palm is not given proper culture, for instance is

allowed to carry a full load of offshoots, and, simultaneously, to bear

all the fruit that it can, it tends to become an intermittent bearer,

bringing in a large crop one year and little or nothing the next. This

should be avoided by eliminating the conditions named.

The

season of ripening is from May to December, depending on variety and

location. Fresh dates as early as May can be secured in favored

locations in Arabia, where certain early kinds are grown. They have not

yet been produced so early in the United States, where the first dates

do not ripen until July. In many regions very late varieties will carry

fruit into mid winter. In California and at Basrah the height of the

season is September; in Egypt, August; in western Arabia, July; in

Algeria, September or early October. As a general rule, the dates of

best quality are late in ripening and the early dates are soft

varieties which must be consumed fresh as they lack the necessary

amount of sugar to keep without fermenting.

American growers

will find an advantage in fairly early varieties (other considerations

agreeing), as the crop can thus be disposed of without competition, say

before November 1, at about which time dates from Persian Gulf or North

African sources can be put on the market, possibly at lower prices.

Picking and

Packing

The

picking process offers no particular problems, although the methods are

not the same with all varieties. Usually two persons can pick together

conveniently, one holding the basket and the other gathering the dates

and placing them in it. Under favorable conditions, some varieties will

mature a whole bunch so evenly that it can be removed entire without

loss, but in many cases it is necessary to pick out the different

"threads" carrying dates, and cut them separately, leaving those whose

fruit is not yet mature for another day. It is advisable, with kinds

that permit of it, to leave the calyx on the fruit, since if this is

pulled off it opens an avenue for the entrance of insects and dirt.

Bunches left to ripen on the tree frequently need to be protected by a

bag of cheese-cloth or similar material, to keep off birds and insects.

Dates

grown for home use need no treatment after picking unless it be a

washing to remove the dust. If they are to be kept for some time, they

may well be pasteurized to free them of insect eggs and the bacteria of

fermentation and decay. Small quantities of fruit can be treated

successfully in the oven of a cookstove, pains being taken by

regulating the aperture of the door, to keep the temperature between

180° and 190° for three hours. This may slightly alter the taste;

sterilization by exposure overnight to the fumes of carbon bisulfide is

easy and causes no change of flavor.

There are many advantages

in ripening dates artificially rather than leaving them to mature on

the tree; hence some method of artificial ripening has been

practiced in most date growing countries since the time of the earliest

written records. Much careful experimentation has been done in this

country, first by the Arizona Experiment Station and later by the

United States Department of Agriculture. As a result, such simple,

satisfactory, and inexpensive methods of maturing dates have been

worked out that the commercial grower will do well to rely on them. The

exact process differs with the variety and with the conditions under

which the dates have to ripen; for the precise technique advisable in

his case the grower must either refer to those who have had the

experience he needs, or experiment on a few dates for himself, after he

has grasped the general principles.

As W. T. Swingle points out,

a date is botanically mature, or "tree ripe" as horticulturists say, as

soon as it reaches full size and the seed is fully developed. At this

stage, however, the date is still astringent and not eatable. Following

this comes a process that may be called "ripening for eating,"

consisting of complex chemical transformations by which the sugars are

altered and the tannin deposited in insoluble form in "giant cells."

This final ripening is brought about by the combination of heat and a

certain degree of humidity.

The principle underlying modern

methods of artificial ripening is, therefore, to expose the dates to a

constant high temperature, while holding them in the humid atmosphere

which is created by the moisture they naturally give off as they dry

and wrinkle.

For this purpose the dates are picked when they

first begin to soften. Most varieties at this stage show translucent

spots while the remainder of the berry is still hard and remains bright

red or yellow in color. Dates taken from the tree in this condition

will ripen successfully in three or four days if they are packed

loosely, stems and all, into a tightly closed box and left at ordinary

room temperature, the room being closed at night to keep out cold air.

Commercial growers provide a special house, or a room built

in

the packing-shed for this purpose. This is so constructed as to be

air-tight when closed, so that the temperature can be maintained at an

even figure, without variation of more than a degree or two, by means

of an electric light or a lamp with thermostat attachment such as is

used in the incubators of poultrymen. Under such conditions, dates will

be brought to a beautiful even maturity and practically without loss by

keeping them from twenty-four to seventy-two hours at a temperature of

110° to 120°.

The skillful grower will control further the

ripening of his dates by irrigation. In some climates, like that of

Upper Egypt and of the Coachella Valley in some seasons, a typically

"soft" date like Deglet Nur will mummify on the palm, as it matures,

until it becomes a "dry" date. This can be avoided by keeping the palms

well irrigated while the dates are ripening. On the other hand, "soft"

varieties sometimes "go to pieces" and ferment on the tree, because of

too much moisture; in this case the soil must be kept dry during the

ripening season.

The packing of dates is a matter for the

grower's own taste, or for standardization by the cooperative

association to which he may belong. Good dates of standard varieties

are usually packed in layers in one-pound cardboard boxes, like

sweetmeats. In California, where home-grown dates bring fancy prices,

great pains are taken with this finest quality of fruit, which is

easily retailed at $1 a pound.

Most dates worth marketing in the

United States are worth packing in cartons. In Arizona, berry-boxes

have been used. The American standard for bulk shipment is the lug-box

of 30 to 40 pounds' capacity. It is important, in any case, that the

pack be uniform, both in size and variety; otherwise the grower can

expect to receive only "cull" prices.

Many varieties, such as

Zahidi, ripen well in the bunch and adhere indefinitely. It is probable

that a profitable trade can be developed in marketing entire bunches of

these, which the retail dealer can display in his store as he does a

bunch of bananas. Dates of inferior quality can be worked up into

various by-products, such as "date butter," or sweetmeats, or may be

sold to bakers and confectioners. Culls are used in the Orient for the

distillation of arrak, or as feed for live-stock. Soft early dates,

which in many cases are of a beautiful color as well as delicious

flavor but which lack keeping quality, probably could be sold in crates

as are berries and be similarly handled as perishable fruits. Marketing

should be carried on through a growers' cooperative association, which

can guard the interests of all by insisting on proper

standards.

For a bearing plantation with fifty

palms to the acre, 100 pounds of fruit to a tree each year is a

conservative estimate of the yield. This means 5000 pounds of fruit an

acre each year, the retail value ranging from 2 cents a pound in the

Orient to $1 a pound in the United States. Growers in the Coachella

Valley have been able for some years to sell practically all the good

dates they produce at 25 cents to 75 cents a pound at the plantation.

Such a price is not likely to be maintained, since dates of many

varieties can be grown, picked, and packed at a total cost of not more

than 5 cents a pound; but there are no present indications of an early

decrease in price. If it should fall to an average of 20 cents a pound,

this would still allow the satisfactory gross income of $1000 an acre

from fruit alone, while the offshoots of good varieties at present

prices ($5 to $15 each) are a valuable factor and may be worth almost

as much to the orchardist as the fruit. Offshoots, in fact, should more

than pay the whole cost of running a young plantation, leaving the

entire proceeds from the fruit as clear profit.

Pests and

Diseases

There are two scale insects, found wherever dates grow, that are

troublesome to the orchardist. The Parlatoria scale (Parlatoria blanchardii

Targ, Tozz.) remains dormant during the winter but is active in summer,

sucking the plant juices from the leaves at the time when growth is

most vigorous. The following description of the insect is condensed

from T. D. A. Cockerell: To the naked eye the scales appear as small

dark gray or black specks, edged with white. If the scale is lifted by

means of a pin or the point of a knife, the soft, plump and juicy

female, of a rose-pink color, is found underneath. The male scales,

which are rarely seen, are much smaller and narrower than those of the

female. About the middle of March the female lays eggs; the larvae

hatch a fortnight later, crawl about restlessly for a time, and then

settle down for the remainder of their lives.

The treatment is

by dipping the offshoots in a solution of 1 gallon of Cresolin, 4

gallons of distillate, and 95 gallons of water. Mature palms may be

sprayed with the same mixture. By these methods this scale is

eventually eliminated.

The more dangerous Marlatt scale (Phoenicococcus

marlatti

Ckll.) is wine-colored, and secretes a white waxy substance. It usually

lives at the base of the leaves, "inside" the palm, where it is almost

inaccessible, coming out at intervals to molt. It can be destroyed by

dipping the offshoots and following this by periodic spraying.

Date

palms in moist regions are often attacked by parasitic fungi, which,

however, yield to bordeaux mixture or other standard fungicides.

In some regions the palm is attacked by a borer (Rhyncophorus)

which, if not destroyed, is fatal to the tree. The only successful

treatment seems to be to watch for the intruder and kill it before it

has penetrated too far. Locusts, grasshoppers, rats, gophers, ants,

bees, wasps, birds, and the like give trouble in various localities.

The treatment resorted to against these pests in connection with other

cultures will also serve for the date palm orchard.

Stored dates are likely to become infested with such common enemies of

stored foods as the fig-moth (Ephestia

cautella Walker) and the Indian meal-moth (Plodia interpundella

Hiibner) , The best protection against these is a packing-house that is

reasonably insect-proof and is fumigated at the beginning of each

season. The modern methods of preparing dates for the market usually

include some system of disinfection which kills insect eggs. It is

reported that in Egypt dates for export are dipped in dilute alcohol,

or in alcohol and glycerine. "Dry" dates can be scalded; "soft" dates

are, in America, frequently pasteurized by dry heat or by fumigation.

Varieties and

Classification

Several

thousand varieties of dates have been recognized, but those which have

any commercial importance are limited to a few score, while those that

are of real merit number only a few dozen, since many kinds owe their

reputation not to excellence of flavor but, as do the Elberta peach and

the Ben Davis apple, to good shipping and keeping qualities.

Varieties

are usually classified as "soft" (or "wet") and "dry," Orientals

classify them by color (yellow or red, before they are cured); by

keeping quality; and as "hot" and "cold," according to whether a

long-continued diet of them "burns" the stomach or not.

The

classification of "soft" and "dry" (which sometimes has been

complicated and confused by the insertion of an inter mediate class of

"semi-dry") is commercially convenient, but not absolute; for

practically any soft date may become a dry date under certain

atmospheric conditions, and most dry dates can be made soft by proper

management and artificial maturation.

The dry dates

predominate in most parts of North Africa, including Egypt, being

preferred by the nomads because they are easily packed and

not

likely to spoil. On the other hand, practically all of the dates which

the world recognizes as valuable are soft varieties. In the following

list, which includes the most important kinds from throughout the

world, there is only one unmistakably dry date (Thuri), which, though

recognized as good in its Algerian home, is given a place in this list

mainly because it has succeeded particularly well in Calirfornia. There

are three others (Asharasi, Kasbeh, and Zahidi) that would probably be

considered dry, but cannot be unequivocably placed in that class.

Asharasi and Kasbeh are much softer than the typical dry date, while

Zahidi at one stage of its maturity is typically soft, and is widely

sold in that condition, although if left long enough on the palm it

becomes actually a dry date. All the other varieties in the list are

typically soft, but most, if not all, of them will be converted into

dry dates if left to ripen on the trees in a sufficiently hot and dry

climate.

The American and European markets are accustomed only

to soft dates, and as most of the good varieties are soft, growers will

naturally give attention to soft kinds by preference. A market for dry

dates, in America at least, will have to be created before any large

quantity can be sold. Nevertheless, Americans who have eaten good dry

dates usually like them, and frequently consider them preferable to

those soft dates, such as Halawi and Khadhrawi, which (often under the

trade name of Golden Dates) have until recently been almost the only

varieties on the American market.

Amri.

— Form oblong, broadest slightly above the center and bluntly pointed

at the apex; size very large, length 2 to 2½ inches, breadth 1 to 1¼

inches; surface deep reddish brown in color, coarsely wrinkled; skin

thick, not adhering to the flesh throughout; flesh about I inch thick,

coarse, fibrous, somewhat sticky, and with much rag close to the seed;

flavor sweet, but not delicate; seed oblong, I¼ to 1½ inches long,

rough, with the ventral channel broad and shallow, and the germ-pore

nearer base than apex. Season late.

More extensively exported from

Egypt than any other variety. It is not, however, a first-class date.

It is large and attractive in appearance, but inferior in flavor. The

keeping and shipping qualities are unusually good. Named probably from

Amr, a common personal name.

Asharasi.

— Form ovate to oblong-ovate, broadest near the base and pointed at the

apex; size medium, length 11/8 to 13/8

inches, breadth 1/8

to I¼ inches; surface hard, rough, straw-colored around the base,

translucent brownish amber toward the apex; skin dry, thin, coarsely

wrinkled; flesh ¼ inch thick, at basal end of fruit hard, opaque,

creamy white in color, toward tip becoming translucent amber, firm;

flavor rich, sweet, and nutty; seed oblong-elliptic, pointed at apex,

5/8 to ¾ inch long, smooth, the ventral channel almost closed, and the

germ-pore nearer base than apex. Ripens midseason.

Syn.

Ascherasi. The best dry date of Mesopotamia, if not of the world. It

can be used as a soft date; having always some translucent flesh at the

apical end of the fruit, it has by some writers been classed as

semi-dry. Grown principally in the vicinity of Baghdad; now also in the

United States, where it succeeds well. The name means Tall-growing.

Deglet Nur.

— Form slender oblong to oblong-elliptic, widest near the center and

rounded at the apex; size large, length 1½ to I¼ inches, breadth ¾ to 7/8

inch; surface smooth or slightly wrinkled, maroon in color; skin thin,

often separating from the flesh in loose folds; flesh ¼ inch

thick, deep golden-brown in color, soft and melting, conspicuously

translucent ; flavor delicate, mild, very sweet; seed

oblong-elliptie, pointed at both ends, about 1 inch long, with

the

ventral channel shallow and partly closed, the germ-pore at center.

Season late.

Syns. Deglet Noor, Deglet en-Nour. This variety is

considered the finest grown in Algeria and Tunisia, where its

commercial cultivation is extensive, and it is highly esteemed in

California, where it holds at present first rank among dates planted

commercially. Its defects are a tendency to ferment if kept for several

months, and the immense amount of heat required to mature it properly.

The name is properly transliterated Daqlet al-Nur, meaning Date of the

Light, an allusion to its translucency.

Fardh.

— Form oblong, widest near the middle and rounded at the apex; size

small to medium, length about I¼ inches, breadth about ¾ inch; surface

shining, deep dark brown in color, almost smooth; skin rather thin,

tender; flesh 1/8 to ¼ inch thick, firm,

russet brown; flavor sweet with a rather strong after-taste; seed

small, length 5/8 inch. Ripens midseason.

Syn.

Fard. This is the great commercial date of Oman, in eastern Arabia. It

has recently been planted in California; American markets are

thoroughly familiar with the fruit through the large

importations which are annually made from Oman. While inferior

in

quality to many other varieties, Fardh holds its shape well when packed

and keeps well. For these reasons it is a valuable commercial variety.

According to modern Omani etymologists, the name means The Separated,

because of the way the dates are arranged in the bunch; but the

ancients, who are entitled to more credit, spell it in a way that means

The Apportioned.

Ghars.

— Form oblong to obovate, narrowest near the rounded apex; size large

to very large, length 1½ to 2 inches, breadth about 7/8

inch; surface somewhat shining, bay colored; skin soft and tender;

flesh 3/8

inch thick, soft, sirupy, slightly translucent; flavor sweet and rich;

seed oblong, ¾ to 1 inch long, with the ventral channel deep and

sometimes closed near the middle, and the germ-pore at center. Season

early.

Syns. Rhars, R'ars. One of the commonest soft dates in

North Africa, esteemed for its earliness in ripening, its

productiveness, and the ability of the plant to resist large amounts of

alkali and much neglect. In California it has proved to be a strong

grower, but the fruit is not so good as that of several other

varieties, and also ferments easily. The name means Vigorous Grower.

Halawi.

— Form slender-oblong to oblong-ovate, broadly pointed or blunt at the

apex; size large, length 1¼ to I¾ inches, breadth about I inch; surface

slightly rough, translucent bright golden-brown in color; skin thin but

rather tough; flesh 1/8 to 3/16

inch thick, firm, goldenamber in color, tender; flavor sweet and

honey-like, but not rich; seed slender oblong, 7/8

inch long, with the ventral channel broadly open. Ripens midseason.

This

is the great commercial date of Mesopotamia, and probably the most

important variety in the world, as regards quantity sold. It is grown

chiefly around Basrah, at the head of the Persian Gulf. It has good

keeping and shipping qualities, but is not esteemed by the Arabs for

eating; in American markets, however, it is preferred to several other

varieties because of its attractive color. Both in California and in

Arizona Halawi has succeeded remarkably well. The name means The Sweet.

Hayani.

— Form oblong-elliptic, broadest slightly below the center and rounded

at the apex; size very large, length 2 to 2½ inches, breadth 1 to 1¾

inches; surface dark brown in color, smooth; skin thick, separating

readily from the flesh; flesh about ¼ inch thick, light brown

in

color, soft; flavor sweet, lacking richness; seed oblong, sometimes

narrowed toward the apex, 1¼ to 13/8 inches

long, with the ventral channel broad and deep, and the germ-pore

usually 3/8 inch from the base. Ripens

midseason.

Syns.

Hayany, Birket al Hajji, Birket el Haggi, Birket el Hadji, and Birkawi.

One of the most satisfactory Egyptian dates in California and Arizona.

It is precocious and prolific, and has proved to be more

frost-resistant than many other varieties. The plant is unusually

ornamental in appearance. The variety is named after the village of

Hayan.

Kasbeh.

— Form

oblong-ovate, widest near the base and broadly pointed at the apex;

size large, about I¾ inches long, ¾ inch broad; surface golden-brown

to chestnut in color; skin thin but fairly tough; flesh 3/16

inch thick, firm, but never hard, tender; flavor sweet, slightly heavy

but not cloying; seed oblong-elliptic, almost an inch long, the

ventral channel open and deep, the germ-pore nearer base than apex.

Season late.

Syns. Kesba, Kessebi, El Kseba. A variety of

ancient origin, extensively cultivated in Algeria and Tunisia. Before

Deglet Nur came into the field it was considered the finest date in

North Africa. It is valued in California, where it has been found to

have excellent keeping and shipping qualities as well as good flavor.

The name means The Profitable.

Khadhrawi.

— Form oblong to oblong-elliptic, widest near the center and broadly

pointed at the apex; size medium to large, length 1¼ to 1¾ inches,

breadth ¾ to 7/8 inch; surface translucent

orange-brown in color, overspread with a thin blue-gray blue; skin

firm, rather tough; flesh, 3/16

to ¼ inch thick, firm, translucent, amber-brown in color; flavor rich,

never cloying; seed oblong-obovate to oblongelliptic, I inch long, the

ventral channel narrow or almost closed. Ripens midseason.

Syns.

Khadrawi, Khudrawee. One of the most important commercial varieties of

Mesopotamia, ranking second only to Halawi. It is a better date than

the latter, but not so highly esteemed on the American market because

of its slightly darker color. In California it has been grown with

great success. The name means The Verdant.

Khalaseh.

— Form oblong to oblong-ovate, broadest near the center and rounded to

broadly pointed at the apex; size medium, length 13/8

to 15/8 inches, breadth ¾ to 7/8

inch; surface smooth, orange-brown to reddish amber in color, with a

satiny sheen; skin firm, but tender; flesh ¼ inch thick, firm, tender,

reddish amber in color, free from fiber; fiavor delicate, with the

characteristic date taste in a desirable degree; seed oblong-elliptic,

pointed at both ends, ¾ to 7/8 inch

long, the ventral channel almost closed. Ripens midseason.

Syns.

Khalasa, Khalasi, Khalas. The most famous date of the Persian Gulf

region, and unquestionably one of the finest in the world. It is grown

principally at Hofhuf in the district of Hasa; a few palms have been

planted in the United States, and have produced fruit of superior

quality. Khalaseh likes a dry situation and sandy soil. It is not a

heavy bearer, but is precocious. The name means Quintessence.

Khustawi.

— Form oblong-oval, broadest near center and rounded at apex; size

small to medium, length 1 to 1½ inches, breadth ¾ to 7/8

inch; surface smooth, glossy, translucent orange-brown in color; skin

thin and delicate; flesh ¼ inch thick, soft and delicate in texture,

translucent golden-brown in color; flavor unusually rich yet not

cloying, with the characteristic date taste in a desirable degree; seed

oblong-obovate, ¾ inch long, pointed at both ends, with the ventral

channel open. Ripens midseason.

Syns. Khastawi, Kustawi,

originally Khastawani (Persian). A delicious dessert date from Baghdad.

It has proved well adapted to conditions in the date-growing regions of

America. It is not a heavy bearer, but the fruit possesses good keeping

qualities. The name means The Date of the Grandees.

Majhul.

— Form broadly oblong to oblong-ovate, broadest at center to slightly

nearer base and broadly pointed at apex; size very large, length 2

inches, breadth 1¼ inches; surface wrinkled, deep reddish brown in

color; skin thin and tender; flesh 3/8 inch

thick,

firm, meaty, brownish amber in color, translucent, with no fiber around

seed; flavor rich and delicious; seed elliptic, 1¼ inches

long,

with the germpore nearest the base and the ventral channel almost

closed. Season late.

Syns. Medjool, Medjeheul. A variety of

large size and good keeping qualities, from the Tafilalet oases in the

Moroccan Sahara, whence the fruit is exported to Europe. Probably

suited only to the hottest and driest regions in the United States. The

name means Unknown.

Maktum.

— Form broadly oblong to oblong-obovate, usually broadest near center

and rounded at the apex; size medium, length 1½ to 1¼

inches,

breadth 7/8 to 1 inch; surface

somewhat glossy, translucent golden-brown in color; skin firm,

wrinkled, rather thin; flesh 3/8 to 5/8

inch thick, soft, almost melting, light golden-brown in color; flavor

mild, sweet, similar to that of Deglet Nur. Season late.

Syn.

Maktoom, originally Makdum. A rare variety from Mesopotamia which has

proved admirably adapted to conditions in California, although not

resistant to frost. It is large and of fine quality. The palm is a

vigorous grower. The name means The Bitten.

Manakhir.

— Form oblong, rounded at the apex; size very large, length 2 to 2¼

inches, breadth slightly more than 1 inch; surface smooth, brownish

maroon in color, with a purplish bloom; skin thin and tender;

flesh ¼ inch thick, soft and melting, with fiber around the

seed;

flavor delicate, resembling that of Deglet Nur; seed oblong, 1 inch

long, with the germ-pore nearer the base and the ventral channel

frequently closed. Season late.

Syns. Menakher, Monakhir. A rare

and large-fruited variety from Tunis, of which only a few palms exist

in the United States. In this country it is not a date of the best

quality. The name means The Nose Date.

Saidi.

— Form oblong-ovate, broadest near the base and blunt at the apex;

size large, length 1½ inches, breadth about 1 inch; surface

almost smooth, brownish maroon in color, overspread with a bluish

bloom; skin thin, tender; flesh 3/16 inch

thick, red-brown in color, firm; flavor very sweet, almost cloying;

seed oblong-elliptic, 7/8 inch long, the

germ-pore slightly nearer the base and the ventral channel almost

closed. Ripens in midseason.

Syns.

Saidy, Wahi. One of the most important varieties of Upper Egypt. It is

not considered so good in quality as some of the Algerian and

Mesopotamian varieties, but it is a heavy bearer, though it requires a

hot climate to ripen perfectly. The name indicates that it comes from

Said or Upper Egypt.

Tabirzal.

— Form broadly oblong-obovate, broadest below center and broadly

pointed at the apex; size medium, length 11/8

to 1½ inches, breadth 7/8

to 11/8

inches; surface translucent deep orange-brown in color, with a

blue-gray bloom; skin thin and tender, coarsely wrinkled ;

flesh ¼

inch thick, soft and tender, translucent orange-brown in color; flavor

distinctive, mild and pleasant, sweet but not cloying; seed broadly

oblong, 5/8 to ¾ inch long, with the

ventral channel narrow. Season late.

One

of the best dates grown at Baghdad. In the United States it is little

known as yet. Originally Tabirzad (Persian) meaning Sugar Candy.

Thuri.

— Form oblong, broadest near center and bluntly pointed at apex; size

large, length I¾ inches, breadth ¾ inch; surface reddish chestnut

color, overspread with a bluish bloom; skin thin; flesh 3/16

inch thick, firm and nearly dry but not hard or brittle, golden-brown

in color; flavor sweet, nutty and delicate; seed oblong, 1 inch long,

the ventral channel deep and partly closed, the germ-pore nearer the

base. A midseason date.

Syns. Thoory, Tsuri. One of the best

Algerian dry dates. It is large, not too hard, and of excellent flavor

; the palm bears heavily and the clusters are of exceptional size. In

California it has proved very satisfactory. The name means The Bull's

Date.

Zahidi.

— Form oblong-obovate, broadest near the rounded apex ; size medium,

length 1¼ inches, breadth 7/8

inch; surface smooth, glossy, translucent golden-yellow in color,

sometimes golden-brown; skin rather thick and tough; flesh ¼

inch

thick, translucent golden-yellow close to the skin, whitish near the

seed, soft, meaty, and full of sirup; flavor sweet, sugary, and not at

all cloying; seed oblong, ¾ inch long, the ventral channel

open.

Season early.

Syns. Zehedi, Zadie, originally Azadi (Persian). A

remarkable date, the principal commercial variety of Baghdad. It can be

used as a soft date (as described above) or as a dry date, depending on

the length of time it is allowed to remain on the palm. The tree is

vigorous, hardy, resistant to drought, and prolific in fruiting. The

name means

Nobility.

1

Malesia, iii

1 S. Dept. Agr., Bull. 28.

Back to

Date Palm

Page

|