From AgAlert, California Farm Bureau Federation

by Ching Lee

Macadamia nuts: Not just a product of Hawaii

The exotic reputation of the macadamia nut can be misleading.

Like pineapples and coconuts, the macadamia has long been synonymous

with Hawaii, where it was first grown as a commercial crop.

And

while the Aloha State went on to dominate world production of the

lavish nut—and did so for decades—that dominance is now being

challenged as other countries are planting their own macadamias.

There's even some competition from across the Pacific—namely, from the

Golden State, where farmers have been known to grow just about anything.

To

be fair, competition from California, in terms of volume, is not much

of a threat to Hawaii—at least not yet. Compared to the millions of

tons of almonds, walnuts and pistachios that come from California farms

each year, the state's production of macadamia nuts is a mere blip on

the radar.

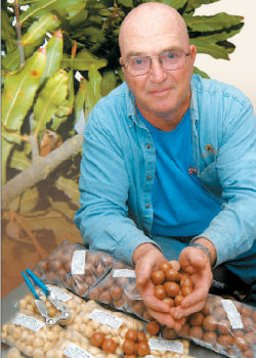

San Diego County farmer Jim Russell has

established a base of customers willing to pay

a premium price for his organic macadamia

nuts, which he sells at farmers markets, to

restaurants and through his mail order business.

But

humble beginnings didn't stop San Diego County farmer Jim Russell from

pursuing the rare and unusual. For Russell, the motivating factor was

simple: He was a big fan of the nut, so much so that he wanted trees of

his own.

"I like the taste of macadamia nuts," he said. "I figured I could sell those little suckers."

Located

in Fallbrook, Russell's 4 1/2 acres of macadamia trees, which he

planted in the 1970s, produce about 16,000 pounds of nuts a year. The

trees are tucked among a hodgepodge of other specialty crops, including

gourds, avocados, lemons, limes, kumquats, pummelos, banana trees,

chestnuts and hachiya persimmons.

Most macadamia farms in

California are small like Russell's, and they're mostly concentrated in

Southern California, especially along coastal regions such as San Diego

and Santa Barbara counties where the climate is frost-free. In the

north, some are found in the Berkeley area and Butte County.

Russell,

who is also president of the California Macadamia Society, a nonprofit

group that teaches farmers about the nut, estimates there are some

3,000 acres of macadamias in the state, a mere fraction of Hawaii's

15,000 acres. Together with Florida, which also grows macadamias on a

small scale, the United States is the world's No. 2 producer of

macadamias, topped by Australia, where the nut originated. Other key

producers include South Africa, Guatemala, Costa Rica and Kenya.

Born

and raised on a Pennsylvania farm that raised chickens and beef cattle,

Russell first latched on to the idea of farming macadamias while he was

working on his master's degree at San Diego State University. As part

of a research project, he did an analysis of the many different crops

that California farmers could grow and discovered that macadamias were

one of them.

"So I did research to see if I thought it was cost effective to do that," he said. "My research said it was, so I did.

"I figured that if I liked (the nuts), so will other people, and they're going to buy them," he added.

Indeed,

people have been buying them. Although macadamias are among the most

expensive nuts on the market, Americans in particular have been

developing an appetite for the rich, buttery kernels and now consume

more than half of the world's production, according to the U.S.

Department of Agriculture. Demand for macadamias is expected to grow as

U.S. consumer income and spending continue to rise.

Good news

about the health benefits of macadamias and other nuts are also helping

to boost worldwide demand. The nuts provide a good source of protein,

calcium, potassium and fiber, but more importantly, they are high in

monounsaturated fats—that's the "good" fat—which means a diet that

incorporates macadamia nuts may help to lower cholesterol and reduce

the risk of heart disease.

And that's good news for growers like

Russell, who sells his nuts at farmers markets, to restaurants and

through his mail order business, where he has established customers who

are willing to pay a premium price for his organic product. He charges

$9.50 a pound for the ready-to-eat kernels and $3.50 a pound for the

in-shell nuts.

California macadamia farmers also sell their

products through Gold Crown Macadamia Association, a growers'

cooperative that's been around since 1971 and handles all the drying,

processing, packaging and shipping for its member-farmers

(www.macnuts.org).

Interestingly, the co-op's No. 1 customer

happens to be owners of exotic birds, primarily macaws, which need the

macadamia's tough shells to chew on to prevent their beaks from getting

soft, said Russell, who doesn't have any bird customers.

"They

eat palm nuts out in the wild," he said of the birds. "Now that they

sit in a cage, they don't have that. So yes, their owners will pay a

premium for those macadamia nuts."

The trees themselves are

large and bushy evergreens. Once mature, the trees are rather hardy,

tolerating temperatures as low as 24 degrees, a blessing for those

farmers who endured last January's freeze that devastated the state's

citrus and other crops. Like farming other tree fruit and nuts,

macadamias require at least four to five years of investment before the

trees begin to produce nuts and six years before the trees are in full

production.

The nuts fall to the ground when they're ripe and

ready to be harvested, which generally happens during the late fall to

early winter but will continue through June, Russell said. Once he

collects the nuts from the ground, he processes them on his farm and

home, where he first removes the exterior husks, then dries them in

trays for a minimum of two weeks, after which the nuts are run through

an additional dryer at 95 degrees for about four days. That takes the

nuts down to about 1 percent moisture.

"At 1 percent moisture, they're almost indestructible and will last almost forever if you keep them dry," Russell said.

Because

the macadamia shells are one of the hardest to crack, Russell uses a

special cracking machine that is strong enough to get through the tough

shell but gentle enough not to crush the kernel inside. Separating the

unblemished kernels from the cracked shell bits is tedious and labor

intensive, hence customers pay a hefty price for shelled macadamias.

|

|