Article from the

West Australian Nut and Tree Crop Association

by Russ Stephenson

Macadamia: Domestication and Commercialisation

The macadamia is

considered one of the world's finest gourmet nuts because of its

unique, delicate flavour, its fine crunchy texture, and rich creamy

colour. Nuts from wild macadamia trees provided a source of food for

the aboriginals in the Australian subcontinent, but Australian farmers

were slow to appreciate the commercial potential of this fine nut.

OriginThe

macadamia nut is the only commercial food crop indigenous to Australia,

originating along the fringes of rainforests in coastal southeast

Queensland and northeast New South Wales (25 to 32°S latitude). The

tree has several features suggesting adaptation to harsh environments,

including sclerophyllous leaves and dense clusters of fine, proteoid

roots that develop to enhance nutrient uptake from poor soils,

particularly those low in phosphorus. Of the four southern species of

macadamia, only two are edible, the smooth-shelled Macadamia integrifolia and the rough-shelled M. tetraphylla.

Only the former has been developed commercially. The latter, grown on

moderate scale in California and New Zealand, produces a raw kernel of

excellent eating quality but contains a higher percentage of sugar that

may caramelise on roasting, thus detracting from its appearance and

reducing its effective shelf life. The wild M. ternifolia produces a

small, unpalatable, bitter kernel. M. jansenii was first discovered in

1982 and there are less than 100 known individuals surviving in the

wild. It has small inedible fruit.

The evergreen macadamia tree is medium to large, attaining a height of up to 20 m and a spread of up to 15 m. In M. integrifolia,

the leaves are arranged in whorls of three and often have spiny,

dentate margins, and short (5-15 mm) petioles. Multiple branches (or

inflorescences) may be produced from each node. The pendulous racemes,

up to 15 cm long and bearing approximately 200 creamy, white flowers,

are borne on hardened wood. Less than 5% of flowers set fruit and the

nuts take 6 months to mature, after which they abscise naturally. The

fruit is a globose follicle in which two ovules develop. As the husk

dries, it splits along a single suture to release the nut, consisting

of a hard, thick, stony, light-tan shell (the seed coat) that encloses

the kernel.

The leaves of M. tetraphylla are

sessile and are arranged in whorls of four. The margins are more

serrated, with up to 40 spines on each each side and, whereas new leaf

growth of M. integrifolia is pale green in colour, young M. tetraphylla leaves are an attractive pink to red colour. Racemes are longer (up to 30 cm) and bear up 500 reddish-pink flowers.

History

A

German explorer, Ludwig Leichhardt, was the first person to collect

macadamia. Some time later, in 1857, Ferdinand von Mueller, the

Director of the Royal Botanical Gardens in Melbourne, and Walter Hill,

the superintendent of the Brisbane Botanical Gardens, discovered a

macadamia tree on the banks of the Pine River, 30 km north of Brisbane.

Von Mueller described the specimen and named it after his good friend,

Dr John Macadam.

One of the earliest macadamia orchards in

Australia was established at Rous Mill, near Lismore, in the early

1880s and it is still producing nuts today. Other small blocks were

planted throughout New South Wales and Southeast Queensland, but the

total area prior to 1960 was less than 100 ha with annual production of

less than 50 tonnes (t) of nut-in-shell.

Although the macadamia

is native to Australia, large-scale commercial development first

occurred in Hawaii after trees were imported by William Purvis, also in

the early 1880s. It was not, however, until the early 1920s that the

first developmental macadamia orchards were established in Hawaii. A

major breakthrough to commercialisation was the development of

efficient cracking machines. The first truly commercial orchards were

established by Castle and Cooke at Keauhou on the island of Hawaii in

1948.

Small nuts of Macadamia ternifolia compared with the

larger commercial nuts of M. integrifolia

The

development of the macadamia industry was supported by research at the

Hawaii Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of Hawaii. An

early achievement was the discovery of the importance of starch

accumulation above girdled branches for successful grafting, resulting

in true-to-type trees that commenced bearing earlier, and produced much

higher yields than seedling trees. J H Beaumont and R H Moltzau

initiated a cultivar selection program in 1936 and William Storey

released the first 5 cultivars from 20,00 bearing trees in 1948, two of

which ('Keauhou'=HAES 246 and 'Kakea'=HAES 501) were the basis for

early commercial orchards in Hawaii, and later in Australia and other

parts of the world. Cultivar trials using grafted trees were

established on all the major islands of Hawaii.

Other important

cultivars released were 'Ilaika' (HAES 333) , 'Kau' (HAES 344), 'Keaau'

(HAES 660), Mauka' (HAES 741) and 'Makai (HAES 800). In 1960, Storey

visited Australia and collected additional new germplasm for evaluation

in Hawaii. Richard Hamilton enthusiastically promoted the development

of the macadamia industry and continued the variety selection work, as

did his student, Phil Ito.

The importance of maintaining high

quality standards in the developing Hawaiian industry was acknowledged

by J C Ripperton, R H Maltzau and D W Edwards, who developed effective

quality assessment procedures for factories. Their simple and

convenient flotation test for maturity was widely adopted. Kernels that

float on tap water have at least 72% oil and are considered mature.

They

also developed the concept of kernel recovery (the percentage of kernel

within the nut), an important quality feature, particularly in those

early days when many orchards were based on variable seedling trees

that produced nuts with thick shells. More recently, Cathy Cavaletto's

postharvest research at the University of Hawaii has underpinned the

high quality of macadamias in the marketplace.

From the early

1950s to the 1970s, research was carried out by B J Cooil, G T

Shigeura, R M Warner, R L Fox and coworkers to overcome nutritional

constraints to productivity in Hawaiian macadamia orchards and to

develop leaf analysis standards for optimum production and quality.

Flowers of Macadamia integrifolia (left) and M. tetraphylla (right)

Yields

were enhanced by applying phosphorus fertilizer to lava and

phosphorus-fixing soils. Excess phosphorus (leaf P greater than 0.1 %),

however, resulted in the formation of insoluble iron phosphates in the

soil, and consequently, leaf chlorosis. This work provided the basis

for the development of macadamia orchards not only in Hawaii, but also

in Australia and other parts of the world.

Macadamias in Australia

It

was not until the early 1960s, when the Hawaiian macadamia industry was

already well established, that efforts were made to develop the

indigenous macadamia as a commercial crop in Australia.

An Australian macadamia orchard in northern New

South Wales bounded by tall windbreak trees

Colonial

Sugar Refiners (CSR) imported superior selections and technical

expertise from Hawaii. Other large commercial operations were soon

established, with income-tax incentives for investment in the industry.

Although CSR imported the best varieties from Hawaii, it became obvious

their performance was often disappointing and they were not necessarily

well adapted to Australian conditions. It was widely acknowledged that

local research was needed to select varieties better adapted to

Australian conditions, and to similarly modify the Hawaiian cultural

technology.

As in Hawaii, the Australian macadamia industry was

fortunate in having a large number of enthusiasts and innovators who

contributed to the improvement of the industry. The most prominent of

these was Norm Greber, widely regarded as the founding father of the

Australian macadamia industry. He was the first Australian to

successfully graft macadamia and was engaged by CSR to help develop

their macadamia nursery. Norm also propagated many trees in his back

yard and selected superior cultivars, including 'Own Choice, 'Own

Venture', 'Renown', 'Ebony' and 'Greber Hybrid'. He received life

membership of both the Australian and the Californian Macadamia

Societies for his contribution to the development of the macadamia

industry and became patron of the Australian Macadamia Society.

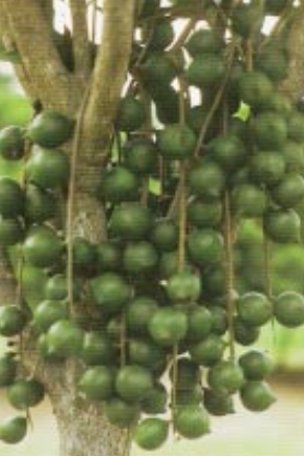

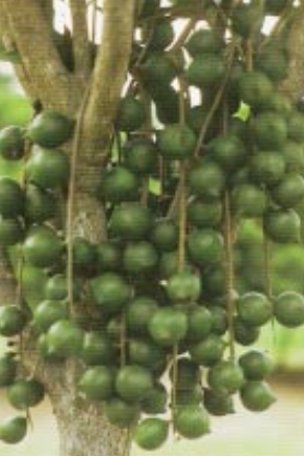

Bunches of macadamia nuts

Stan

Henry, the CSR nursery manager, subsequently developed a novel punch

budding technique using a modified, spent 0.303 brass bullet shell to

remove an oval patch of bark from the rootstock that was replaced with

a patch containing a single bud from the commercial scion.

This

rapid, effective technique gave CSR a considerable advantage over

nurseries employing conventional grafting techniques. The success of

punch budding was largely due to careful selection of budwood with bark

that lifted readily. The CSR nursery supplied all the trees for the

first large-scale commercial orchards at Baffle Creek, north of

Bundaberg, Maleny, Peachester, Mt Bauple, and Rockhampton, totalling

over 1,000 ha. In the 1970s, the first commercial processing plant was

established by CSR. Soon after, other factories were established by

Suncoast Gold Macadamias and by the Macadamia Processing Co and

Macadamia Plantations of Australia. Today, there are about 10 factories

operating in Australia.

The Australian Macadamia Society

The

macadamia industry in Australia is particularly fortunate in having

forged a strong and effective organisation, the Australian Macadamia

Society Limited (AMS). It was established in 1974 by a small group of

enthusiasts eager to share the benefits of their experience and their

innovative ideas. Ever since, it has responded to needs and

opportunities across the whole industry. It fosters the dissemination

of information through its bimonthly News Bulletin, website, MacGroup

meetings, field days, and annual conferences. These very effective and

powerful extension functions complement services provided by State

Departments of Agriculture.

Perhaps the most significant

initiative of AMS was the active encouragement of research into

production, processing and promotion of the crop. Initially, research

was funded from a voluntary levy. In 1993, a production levy,

attracting a subsidy from the Commonwealth Government, was introduced.

This intensified research activity and flow-on benefits to the

industry. The industry levy is currently 25.21 cents/kg total kernel of

which 17.4 c/kg is for product promotion and marketing, amounting to an

annual budget of about A$2 million. A further A$2 million is invested

in research each year, half of which comes from the Commonwealth

Government as a matching dollar for dollar subsidy. Part of the levy is

also used for regular chemical residue testing to maintain Australia's

reputation for producing high quality, quality-assured kernel.

Premium macadamia kernels

Research in Australia

One

of the great challenges was the selection of genetic material better

adapted to Australian environments. In Hawaii, over 100,000 trees were

screened to select the commercial cultivars that are widely used today,

whereas in Australia, fewer than 20,000 seedlings have been screened.

Two of Henry Bell's Hidden Valley cultivars (A4 and A16) are registered

under Plant Breeders Rights legislation and widely grown commercially,

together with subsequent releases.

The AMS currently funds a

major plant breeding program to develop superior cultivars for

Australia. To assist in the search for, and development of, better

adapted cultivars, the AMS has also provided funds to conserve a wide

range of germplasm from native rainforests before they are lost forever

by land clearing.

A macadamia fingerwheel harvester significantly reduces

harvesting cost

Early

macadamia yields in Australia were generally quite low compared with

those reported from Hawaii, although some trees approached the Hawaiian

yield standard of 45 kg nut-in-shell. Yields of 30 kg are more common

and productivity continues to improve steadily with better technology.

It seems that one of the factors contributing to lower yields in

Australia, and many other countries, is harsher environments with

larger diurnal and seasonal variations in temperature than in the mild,

equable climate of Hawaii.

Understanding the influence of

environment on macadamia growth and production was an essential

objective of early macadamia research (and management). The mature

macadamia is capable of withstanding mild frosts to as low as -6 °C for

short periods, but extended periods or lower temperatures may severely

damage or kill mature trees.

Even where trees survive, frosts

may burn off inflorescences and thus seriously reduce cropping. Optimum

temperature for tree growth and photosynthesis is about 26 °C.

Temperature is a major factor influencing vegetative flushing, which,

in turn, influences floral initiation, nut growth, yield and quality.

Most

genera of Proteaceae grow only in climates where there is a long dry

season. Drought, however, limits yield and results in small nuts with

undeveloped kernels. Research at the Maroochy Research Station in a

through-draining lysimeter showed that even mild stress during nut

development, particularly the oil accumulation stage, adversely

affected both yield and quality.

Fortunately, the macadamia has

few serious ease problems and when these occur they tend to be

localised. An example is a husk spot fungus (Pseudocercospora), which induces nuts drop early in the harvest season before they fully mature.

In

Australia, its place of origin, the macadamia is attacked by more than

150 pest species, although parasites and predators usually provide

considerable control. Insects that commonly reduce yields include macadamia flower caterpillar (Homoeosoma vagella), fruit spotting bug (Amblypelta nitida), banana spotting bug (AmbIypeIta lutescens), macadamia nutborer (Crytophlebia ombrodelta) and macadamia felted coccid (Eriococcus ironsidei).

Any of these has the capacity, during severe infestations, to destroy

the crop. An integrated pest management system for insect pest control

has been adopted.

Pest population levels are monitored in the

orchard by pest scouts and chemical sprays are only applied when

threshold pest population levels are reached. This approach maximizes

the contribution of natural enemies in suppressing pest populations

below economic threshold levels. PM has contributed to the

profitability of macadamia growing.

Early nutrition work in

Australia refined the Hawaiian standards to suit Australian conditions.

It was found that small, frequent applications of nitrogen, for

example, effectively restricted tree growth but actually increased

yield and quality of nuts. Many of the soils on which macadamias are

grown in Australia are low in boron, and foliar boron sprays improve

both yield and quality (kernel recovery). As in Hawaii, phosphorus

deficiency limited yields on phosphorus-fixing ferrosol soils.

Mechanical pruning of a high density macadamia orchard

Because

of the long break-even period (10-12 years) for a net return on money

invested in macadamias, the Australian industry moved towards

high-density plantings to increase early cash flow. Mechanical pruning

is used to maintain hedgerows and allow normal orchard operations such

as spraying and harvesting.

The AMS responded to indifferent

quality by adopting stringent quality standards and financial

incentives to encourage growers to sort poor quality nuts from their

consignments. This significant step has enhanced Australia's reputation

on world markets as a supplier of consistently high quality kernel. The

industry places a lot of importance on maintaining this reputation. It

has developed a 'Code of Sound Orchard Practices' to help achieve this.

Commercialisation

World

consumption of macadamias accounts for only about 2-3% of all tree

nuts. For example, only 23,000 t of macadamia kernels is consumed

compared with 650,000 t of almonds, 370,000 t of walnuts, 330,000 t of

hazelnuts, 250,000 t of cashews, 200,000 t of pistachios and 110,000 t

of pecans. There is, therefore, considerable scope for expanding world

markets.

Figure 1. World macadamia consumption (t) (2003).

Source: Australian Macadamia Society (www.macadamias.org);

US Embassy, Canberra; Hargreaves (2004).

The

USA is still the largest market for macadamias, which are particularly

popular in cookies (Fig. 1). Bakery products account for about 40% of

world production. Another 35% is used as snacks, 22% is coated in

chocolate, mainly for the Japanese market, and about 3% used in ice

cream. The Australian industry is actively investing in promotion of

macadamias to diversify its markets, particularly into Japan, Europe

and Asia.

Although Australia's production of macadamias was only

about 25% of that of Hawaii's in 1987, Table 1 shows that it is now

greater, particularly the production of kernel. Australia has a

considerable advantage due to a higher kernel recovery. Nearly half the

world's macadamia exports come from Australia. Massive expansion of

plantings continues, particularly in Australia and South Africa. There

are now over 5 million trees planted on 15,000 ha in Australia, with

production valued at around A$150 M, at the farm gate.

| Table

1. World macadamia production and exports. Sources: Australian

Macadamia Society (www.macadamias.org); Australian Bureau of

Statistics; US Embassy, Canberra; Hawaii Agricultural Statistics

Service, July 12 2004; World round-up reports (Proceedings of the

Second International Macadamia Symposium, Tweed Heads, Australia, 2003). | | Country or region | Area

(ha) | Trees

(000) | 2003 production (t) | % Kernel recovery exports (t) | Kernel recovery exports (t) | | NIS+ | Kernel | | Australia | 15,000 | 5,000 | 30,000 | 9,100 | 32 | 7,460§ | | Central America | 8,700 | - | 17,000 | 3,100 | 18 | 3,100 | | USA (Hawaii) | 7,284 | 1,350 | 27,240 | 4,500 | 25 | 200 | | South Africa | 7,000 | 3,073 | 12,500 | 3,400 | 28 | 2,975 | | Kenya | 6,500 | 1,000* | 8,800 | 1,000 | 16 | 1,000 | | Brazil | 6,000 | - | 3,000 | 600 | 17 | ca 540 | | Malawi | 5,112 | 1,022 | 4,000 | 1,000 | 25 | 1,000 | | Zimbabwe | - | - | 900 | 120 | - | 120 | | * Estimate +Nut-in-shell § 6,400 t of Australia's production was exported as nut-in-shell in 2002-2003. |

Health Benefits

Macadamias,

like other nut crops, have a high oil content (>72%) and for a long

time were considered by nutritionists to be less desirable in healthy

diets. Research, dietary trials and population studies, however,

demonstrate that macadamias contain a range of nutritious and health

promoting constituents. These include monounsaturated fats, proteins,

dietary fibre, minerals, vitamins, and phytochemicals.

The composition of both raw, dried and roasted macadamias typically contain:

• Natural oils: 75%;

• Moisture: 1.5%;

• Protein: 9.4%;

• Dietary fibre: 7.7%;

• Carbohydrates: 4.7%;

• Mineral matter: 1.6% including Potassium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Calcium, Selenium, Zinc, Copper and Iron;

• Vitamins: Vit. B1, 82, B5, B6, Vit, E, plus niacin and folate;

• Phytochemicals: Antioxidants including polyphenols, amino acids, selenium and flavanols plus plant sterols;

• Energy value: 3000 kilojoules per 100 g (727 calories)

Macadamias

contain no cholesterol or trans-fatty acids. They do contain a higher

percentage of monounsaturated oils than any other natural product.

Macadamia oil is similar to olive oil in composition and use.

Macadamias are low in damaging saturated fats and in polyunsaturated

fats that oxidize readily. Diets containing moderate fat levels promote

satiety and have been shown to be sustainable and enjoyable in the long

term. The desirable Mediterranean Health Pyramid diet has 40% of the

food energy from fat.

Separate dietary trials with macadamias in

Australia and Hawaii have demonstrated a significant reduction in total

cholesterol, total triglycerides and the undesirable low-density

cholesterol, but little or no effect on the desirable high-density

cholesterol. They, like many tree nuts, have been shown to lower blood

pressure in hypertensive people and reduce the risk of heart disease,

Current research includes a full biochemical analysis and nutritional

profiling of macadamias and, in the USA, a phytochemical analysis is

close to completion.

The Future

Macadamia

plantations require a large capital investment and take several years

to commence bearing. There is also the risk of declining prices with

increasing world production, although this has not occurred yet. The

industry's investment in promotion and marketing will secure a sound

future, despite competition from countries like Brazil with low

production costs. The Australian industry has developed advantages in

cultural technology through its investment in research. This investment

will continue to help overcome remaining constraints to productivity

and profitability. The future success of the Australian macadamia

industry is assured by the enthusiasm, cohesion and innovative spirit

of all those who are involved in this young, dynamic industry.

Further reading

Gallagher,

E C, O'Hare, P J, Stephenson, R. A, Waite, G, and Vock, N. 2003.

Macadamia problem solver and bug identifier. Field Guide. Queensland

Department of Primary Industries, Brisbane.

Hargreaves, G. 2004. Growth of the macadamia industry: From bush tucker to the king of nuts. Australian Nutgrower, 18: 26-29.

Ironside, D A. 1981. Insect pests of macadamia in Queensland, Queensland Department of Primary Industries, Brisbane.

Nagao, M A and Hirae, H H. 1992. Macadamia: Cultivation and Physiology. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 10:441- 470.

O'Hare,

P J, Quinlan, K, Stephenson, R A, Vock, N et al. 2004. Macadamia

grower's handbook. Growing Guide, Queensland Department of Primary

Industries and Fisheries, Brisbane, 2l4 p.

Power, J. 1982. Macadamia power. Tudor Press, Brisbane p. 6-44.

Shigeura,

G T and Ooka, H. 1984. Macadamia nuts in Hawaii: History and

production. Univ. Hawaii, College of Tropical Agr. & Human

Resources, Res. Ext. Ser. 039.

Stephenson, R A. 1990. The macadamia: From novelty crop to new industry. Agri. Sc. NS 3: 38-43.

Dr

Russ Stephenson is a Senior Principal Horticulturist with the

Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries at the

Maroochy Research Station, where he has carried out research on

macadamia, horticultural agronomy and physiology over the past 24

years. Russ is Secretary of the Australian Society of Horticultural

Science and a member of the ISHS Council.

Back to

Macadamia Smooth Shell Page

Macadamia Rough Shell Page

|

|