Black Mulberry Tree (Morus nigra)

My favorite berry is black mulberry, because it is so delicious,

and such a rare treat to eat in Seattle. I have requested that a black

mulberry tree be planted on my grave.

Most people in Seattle

have never eaten a black mulberry, simply because extremely few black

mulberry trees exist in the city. Some of us have eaten mulberries that

were black — but which came from other species of Morus.

For example, the common white mulberry tree, Morus alba,

has berries that vary at maturity from white, pink, red, purple or

black, and vary in size, too. Moreover, the “Illinois Everbearing”

hybrid of Morus alba and Morus rubra ripens black mulberries (I wrote an article about it in 1990; read it here).

The original, pure black mulberry tree, Morus nigra, is unusual compared to most — if not all — other Morus

species. Its chromosome count is astonishingly high (2n = 308)! It is

almost certainly an ancient hybrid cultivar whose ancestral species are

extinct. It has been cultivated for millennia and its original native

locale is unknown — but likely central Asia.

Its English names,

beside black mulberry, are Persian, Spanish, or common mulberry. It was

introduced to the British Isles by 1548 if not earlier. It was being

offered in North American nurseries by 1771, but is still rare here. In

most parts of this continent it is ill-suited. Much of the interior is

too cold; much of the Southeast too hot and humid. On the Pacific Coast

from B.C. through California it thrives. But few specimens exist.

As an ornamental species its role is modest. It utterly lacks

floral beauty. Its fall color is a late, ordinary yellow. The summer

foliage is darkest green, dense and inelegant. When the ripening fruit

is red it is pretty; when the fruit turns black and drops, staining the

ground most messily, there is no joy. And, as usually seen these days,

when black mulberry is grafted up on a trunk of a white mulberry, the

result is a crude-looking unnatural freak.

But! To eat the fully ripe berries is a sensual foretaste of the delights of heaven.

The

black mulberry’s fruit is the connoisseur’s choice. All mulberries are

eaten mostly by birds and children. They ripen a few at a time, must be

picked daily, and are so plump with juice and so soft and tender that

conveying any to markets is awkward.

Therefore, if you desire to

eat mulberries you must either grow your own or know of a tree nearby.

And if you can grow enough to take weekly to local markets, they will

fetch premium prices.

A Seattle back-yard Black Mulberry dating from the

early 1950s (2008)

I here quote from John Loudon‘s 1883 Trees and Shrubs, an English book:

“The

tree will grow in almost any soil or situation that is tolerably dry,

and in any climate not much colder than that of London. It is very

easily propagated by truncheons or pieces of branches, 8 or 9 feet in

length, and of any thickness, being planted half their depth in

tolerably good soil; when they will bear fruit in the following year.

Every

part of the root, trunk, boughs, and branches may be turned into plants

by separation: the small shoots, or spray, and the small roots, being

made into cuttings; the large shoots into stakes; the arms into

truncheons; and the trunk, stool, and roots being cut into fragments,

leaving a portion of the bark on each.” (page 707).

If

this ease of own-root propagation holds true, then why are virtually

all the trees currently sold in Washington grafted on white mulberry

trunks? I suspect it is because the propagator gets a faster turnover;

it is easier to do. My concern is that the grafted trees look ugly, and

there may well be delayed graft incompatibility. All the very old Morus nigra trees I have seen on the Pacific Coast are own-root.

You

can grow an isolated black mulberry tree and get ripe berries. It has

both male and female flowers, is wind-pollinated and self-fertile. It

tends to be slow growing, putting much energy into fruit. I bought a

small grafted specimen in 2000 and it finally bore fruit this year

(2009).

John Gerard described the berries in his 1593 Herbal:

“The

fruit is long, made up of a number of little graines, like unto a

black-Berrie, but thicker, longer, and much greater, at the first

greene, and when it is ripe blacke, yet is the juyce (whereof it is

full) red.”

Though mulberries look like blackberries, the nearest plant genus to Morus is Ficus.

The

fruit is only to be eaten when fully ripe: dark, very plump, soft and

juicy, readily falling off the tree. In Seattle that means late June at

earliest, more likely mid-July into October. Unripe berries can be

harmful. The berries are rich in vitamin C, potassium, iron, and

antioxidant anthocyanins.

Some cultivars that are thought to be

Morus nigra are: Black Beauty, Chelsea, Jerusalem, Kaester, King James

the 1st, Noir of Spain. Various other named entities ascribed to this

species are really from other species or hybrids — as far as I can

determine.

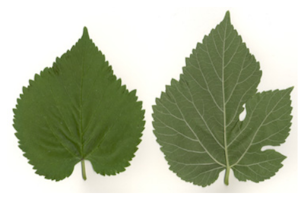

Black Mulberry Leaves

Black

Mulberry leaves — as my scan shows — are roundish overall, heart-shaped

at their bases, on short stalks. They are lobed rarely. They are dark

and semi-glossy above, paler and fuzzy beneath. They measure mostly 3

to 5 inches, up to at most 9 inches.

Authentic black mulberry

trees have been measured over 50 feet tall, in London, but the vast

majority are low, broad, and often the size of a small apple tree.

Based on photographs I have seen, and its size, the so-called “National

Champion” black mulberry tree, in Westminster, Carroll County,

Maryland, is a White Mulberry tree (Morus alba L.).

Since 1955 it has been misidentified thus. As of 1999 it was said to be

60 feet tall and 80 feet wide. In my own travels on the Pacific Coast,

the largest black mulberry trees are around 30 feet tall and are often

wider than tall.

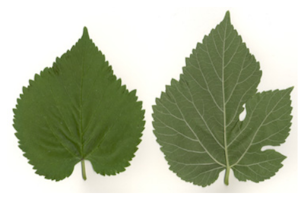

White Mulberry Leaves

White Mulberry is exceedingly variable, from India, China, Korea, Japan, and so on. Its foliage is the silkworm’s food. Morus alba synonyms include: M. acidosa Griff; M. australis Poir; M. bombycis Koidz; M. Kagayamæ Koidz.

Some

botanists split these into separate species, but despite minute

technical differences, their overall appearance and behavior is like

that of white mulberry.

The black mulberry, compared to the

white mulberry: is later to flush in spring, holds its leaves later in

fall, has thicker leaves on shorter stalks, is bisexual, is notably

hairy, has more milky sap, is only a small tree, invariably has black

berries, is less cold-hardy, and its berries taste better to most

people.

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra L). is native in the eastern half of the United States, and requires a continental climate to thrive, so is a flop in Seattle.

Paper Mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L’Her. ex Vent. is east Asian and does poorly in Seattle’s climate.

About Arthur Lee Jacobson

A

lifelong Seattle resident, Arthur developed a passion for plants at 17

and has made his living growing, photographing, and writing about

plants. He is a rare expert who can speak about wild plants, garden

plants, and house plants.

Arthur has a special interest in edible plants, and, in his field guide Wild Plants of Greater Seattle, he includes comments on the edibility, taste, and uses of plants found in the city.

|