From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Japanese Persimmon

Diospyros

kaki L.

EBENACEAE

In great contrast to the native American persimmon, Diospyros virginiana

L., which has never advanced beyond the status of a minor fruit, an

oriental member of the family Ebenaceae, D. kaki L. f ., is

prominent in horticulture. Perhaps best-known in America as the

Japanese, or Oriental, persimmon, it is also called kaki (in Spanish,

caqui), Chinese plum or, when dried, Chinese fig.

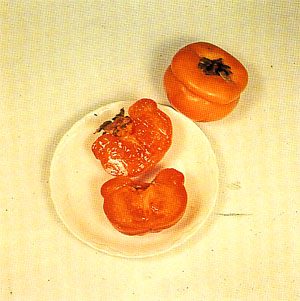

Plate LIX: JAPANESE PERSIMMON, Diospyros

kaki 'Tamopan'

Description

The tree, reaching 15 to 60 ft (4.5-18 m) is long-lived and typically

round-topped, fairly open, erect or semi-erect, sometimes crooked or

willowy; seldom with a spread of more than 15 to 20 ft (4.5-6 m). The

leaves are deciduous, alternate, with brown-hairy petioles 3/4 in (2

cm) long; are ovate-elliptic, oblong-ovate, or obovate, 3 to 10 in

(7.5-25 cm) long, 2 to 4 in (5-10 cm) wide, leathery, glossy on the

upper surface, brown-silky beneath; bluish-green, turning in the fall

to rich yellow, orange or red. Male and female flowers are usually

borne on separate trees; sometimes perfect or female flowers are found

on male trees, and occasionally male flowers on female trees. Male

flowers, in groups of 3 in the leaf axils, have 4-parted calyx and

corolla and 24 stamens in 2 rows. Female flowers, solitary, have a

large leaflike calyx, a 4-parted, pale-yellow corolla, 8 undeveloped

stamens and oblate or rounded ovary bearing the style and stigma.

Perfect flowers are intermediate between the two. The fruit, capped by

the persistent calyx, may be round, conical, oblate, or nearly square,

has thin, smooth, glossy, yellow, orange, red or brownish-red skin,

yellow, orange, or dark-brown, juicy, gelatinous flesh, seedless or

containing 4 to 8 flat, oblong, brown seeds 3/4 in (2 cm) long.

Generally, the flesh is bitter and astringent until fully ripe, when it

becomes soft, sweet and pleasant, but dark-fleshed types may be

non-astringent, crisp, sweet and edible even before full ripening.

Origin and Distribution

The tree is native to Japan, China, Burma and the Himalayas and Khasi

Hills of northern India. In China it is found wild at altitudes up to

6,000-8,000 ft (1,830-2,500 m) and it is cultivated from Manchuria

southward to Kwangtung. Early in the 14th Century, Marco Polo recorded

the Chinese trade in persimmons. Korea has long-established ceremonies

that feature the persimmon. Culture in India began in the Nilgiris. The

tree has been grown for a long time in North Vietnam, in the mountains

of Indonesia above 3,500 ft (1,000 m) and in the Philippines. It was

introduced into Queensland, Australia, about 1885.

It has been cultivated on the Mediterranean coast of France, Italy, and

other European countries, and in southern Russia and Algeria for more

than a century. The first trees were introduced into Palestine in 1912

and others were later brought in from Sicily and America.

Seeds first reached the United States in 1856 when they were sent from

Japan by Commodore Perry. Grafted trees were imported in 1870 by the

U.S. Department of Agriculture and distributed to California and the

southern states. Other importations were made by private interests

until 1919. Seeds, cuttings, budwood and live trees of numerous types

were brought into the United States at various times from 1911 to 1923

by government plant explorers and the tree has been found best adapted

to central and southern California, Arizona, Texas, Louisiana,

Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, southeastern Virginia, and northern

Florida. A few specimens have been grown in southern Maryland, eastern

Tennessee, Illinois, Indiana, Pennsylvania, New York, Michigan and

Oregon.

By 1930, California had over 98,000 bearing trees and nearly 97,000

non-bearing, on 3,000 acres (1,214 ha). California production in 1965

amounted to 2,100 tons. Real estate development reduced persimmon

groves to 540 acres by 1968. In 1970, California produced 1,600

tons–92% of the total U.S. crop.

In parts of Central America, Japanese persimmons have been planted from

sea-level to 5,000 ft (1,524 m). The tree was first grown in Brazil by

Japanese immigrants. By 1961, the total crop was 2,271,046,000 fruits,

mainly in the State of Ceará, followed by Pernambuco and

Piaui, with Bahia far behind. At present, the largest orchards are

mainly in the States of Sao Paulo, Parana and Rio Grande do Sul, with

lesser groves in Minais Gerais and Espirtu Santo. Of 111,412 acres

(45,088 ha) all told, 60,336 acres (24,418 ha) are in Ceará.

Israel and Italy have developed commercial plantings, and cultivar

trials began in 1976 with a view to establishing persimmon-growing for

export in southeastern Queensland.

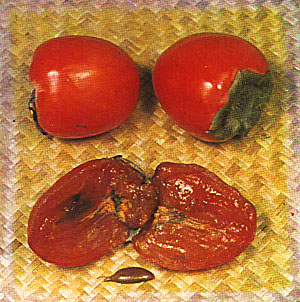

Plate LX: JAPANESE PERSIMMON, Diospyros

kaki 'Tanenashi'

Cultivars

Of the 2,000 cultivars known in China, cuttings of 52, from the

provinces of Honan, Shensi and Shansi, were brought into the United

States in 1914. J. Russell Smith, an esteemed economic-geographer,

collected a number of types near the Great Wall of China in 1925 and

some of the trees still survive in his derelict orchard in the Blue

Ridge Mountains of southern Virginia.

Over 800 kinds are grown in Japan but less than 100 are considered

important. Among prominent cultivars are the non-astringent 'Fuyu',

'Jiro', 'Gosho' and 'Suruga'; the astringent 'Hiratanenashi',

'Hachiya', 'Aizumishirazu', 'Yotsumizo' and 'Yokono'. It was formerly

believed that the flesh color and astringency can vary considerably

depending on whether or not the flowers were effectively pollinated,

and cultivars were classed as: 1) Pollination Constants; and 2)

Pollination Variants.

It has been recently discovered that there are two different mechanisms

affecting astringency; one is degree of pollination, the other is the

amount of ethanol produced in the seeds and accumulated in the flesh.

Pollination Variant fruits with naturally high levels of ethanol lose

astringency on the tree. So does Pollination Constant 'Fuyu' but other

non-astringent Pollination Constant cultivars have been found to have

low levels of ethanol. Pomologists at Kyoto University, Japan, have

classified 40 cultivars into 4 types depending upon the ways or degrees

their fruits lose astringency on the tree and upon flesh color

–Pollination Constant Non-astringent (PCNA), Pollination

Variant Non-astringent (PVNA), Pollination Variant Astringent (PVA) and

Pollination Constant Astringent (PCA). They evidently have not studied

seedless cultivars.

Dr. H.H. Hume, of the University of Florida, separated 13 seeded and

seedless (or nearly seedless) cultivars according to the earlier

pollination classification, and Drs. Camp and Mowry added 'Fuyu'. The

following 8 comprise Group 1:

'Costata'–conical,

pointed, somewhat 4-sided, 2 5/8 in (6.5

cm) long, 2 1/8 in (5.4 cm) wide, with salmon-yellow skin, light-yellow

flesh, with no seeds; or dark flesh and a few seeds. Astringent until

fully ripe, then sweet; late (Oct.-Nov. in Florida). Keeps very well.

'Fuyu' (or 'Fuyugaki')–oblate,

faintly 4-sided, 2 in (5 cm)

long; 2 3/4 in (7 cm) wide; skin deep-orange; flesh light-orange; firm

when ripe; non-astringent even when unripe; with few seeds or none.

Keeps well; excellent packer and shipper. It is the most popular

non-astringent persimmon in Florida. 'Matsumoto Early Fuyu' ripens

three weeks earlier.

'Hachiya'–oblong-conical,

3 3/4 in (9.5 cm) long, 3 1/4 in

(8.25 cm) wide; skin glossy, deep orange-red; flesh dark-yellow with

occasional black streaks; astringent until fully ripe and soft, then

sweet and rich. Seedless or with a few seeds. Midseason to late. Much

used in Japan for drying. Tree vigorous, well-formed and prolific in

Kulu Valley, India. Scanty bearer in southeastern United States; does

well on D. virginiana in Florida, but tends to growth-ring cracking;

often prolific in California.

'Ormond'–oblong-conical,

2 5/8 in (6.5 cm) long, 1 7/8 in

(4.7 cm) thick. Skin reddish-yellow with thin bloom; flesh orange-red,

moderately juicy; seeds large. Very late (Nov. and Dec. in Florida).

Keeps well.

'Tamopan'–Introduced

from China in 1905, again in 1916

(S.P.I. Nos. 16912, 16921, 26773). Broad oblate, somewhat 4-sided;

indented around the middle or closer to the base; 3 to 5 in (7.5-12.5

cm) wide; skin thick, orange-red; flesh light-orange, usually

astringent until fully ripe, then sweet and rich. In some parts of

China and Japan said to be non-astringent. Seedless or nearly so. Of

medium quality; late (Nov.) in Florida; midseason in California. Was

being grown commercially in North Carolina and at Glen St. Mary,

Florida, in 1916.

'Tanenashi'–round-conical,

3 1/3 in (8.3 cm) long, 3 3/8 in

(8.5 cm) wide; skin light-yellow or orange, turning orange-red; thick;

flesh yellow, astringent until soft, then sweet; seedless. Early;

prolific. Much esteemed. Much used for drying in Japan. Leading

cultivar in southeastern United States without pollination. In

California tends to bear in alternate years.

'Triumph'–oblate,

faintly 4-sided; of small to medium size;

skin yellowish to dark orange-red. Flesh yellowish-red, translucent,

soft, juicy; seedless or with 5 to 8 seeds; astringent until fully

ripe, then sweet. Of high quality. Medium-late. In Florida begins in

September and lasts until mid-November.

'Tsuru'–long-conical,

pointed; 3 3/8 in (8.5 cm) long, 2 3/8

in (6 cm) wide; skin bright orange-red, turning red with purple bloom

when mature; flesh orange-yellow or dark-yellow, granular; astringent

until fully ripe; with few or no seeds. Very late.

Group 2:

'Gailey'–roundish

to conical with rounded apex; small; skin

dull-red, pebbled; flesh dark, firm, juicy, of good flavor. Bears many

male flowers regularly and is planted for cross-pollination.

'Hyakume'–round-oblong

to round-oblate, somewhat 4-angled and

flat at both ends; 2 3/4 in (7 cm) long, 3 1/8 in (8 cm) wide; skin

pale dull-yellow to light-orange, with brown russeting when ripe; flesh

dark-brown, crisp, sweet, non-astringent whether hard or ripe.

Midseason. Fairly good quality; somewhat unattractive externally.

Stores and ships well.

'Okame'–round-oblate,

2 3/8 in (6 cm) long, 3 1/8 in (8 cm)

wide; skin orange-yellow turning to bright-red with waxy bloom; flesh

light but brownish around the seeds; sometimes seedless; sweet, of

excellent quality. Fairly early, beginning about Sept. 1 in Florida.

Productive.

'Yeddo-ichi'–oblate,

2 1/2 in (6.25 cm) long, 3 in (7.5 cm)

wide; skin dark orange-red with a bloom; flesh dark-brown with purplish

tint; sweet, rich, non-astringent whether hard or ripe. Of high quality.

'Yemon'–oblate,

4-sided; 2 1/4 in (5.7 cm) long, 3 1/4 in

(8.25 cm) wide; skin light-yellow becoming reddish with orange-yellow

mottling; flesh red-brown or light-colored, astringent at first, sweet

after softening; seedless or with few seeds and then dark around the

seeds. Of high quality, but becomes too soft for shipping.

'Zengi'

('Zengimaru')–round or round-oblate, 1 3/4 in (4.5

cm) long, 2 1/4 in (5.6 cm) wide. Skin dark orange-red or yellow-red;

flesh dark with black streaks; sweet even when hard; with some seeds.

Early, prolific; of medium quality.

Cultivars that are especially hardy in Maryland, Pennsylvania and

Virginia include: 'Atome', 'Benigaki', 'Delicious', 'Eureka', 'Great

Wall', 'Manerh', 'Okame', 'Peiping', 'Pen', 'Shaumopan', 'Sheng,'

'Tsurushigaki', 'Yokono', etc.

'Delicious'

is oblate, medium to large; skin is smooth, light-red;

flesh light-yellow, non-astringent when hard, but more flavorful when

soft; contains a few seeds; tree is vigorous and a regular bearer.

'Eureka'

(from Texas) is oblate, medium to large, puckered at calyx,

bright orange-red, astringent; of good quality; drought and

frost-resistant; late (Nov. in Florida). One of the most satisfactory

in Florida.

'Great Wall'

is small, flat, 4-sided with fine black stripes extending

from the calyx; astringent, dry-fleshed; tree is vigorous, a biennial

bearer; does well in Florida.

'Hanafuyu'

is oblate, non-astringent and usually seedless;

late-midseason; tree is small, bears regularly but yield is low; prone

to premature shedding of fruit; fairly common in northern Florida.

'Ichikikeijiro'

is medium-large, orange, non-astringent;

early-ripening; tree is not vigorous but still this cultivar is among

the best of the non-astringent class in Florida.

'Jumbu'

resembles 'Fuyu' but is somewhat more conical and larger;

non-astringent; edible either firm or soft. Ripens a little later than

'Tuyu'; of good quality.

'Ogasha' is

oblate, non-astringent and usually seedless; prone to

immature shedding of fruit; fairly common in northern Florida.

'Sheng' is

large, ribbed, puckered at calyx, astringent; popular in

Florida; bears annually when pollinated.

'Shogatsu'

is flattened, non-astringent, of fair quality; bears an

abundance of male flowers. Does well in Florida.

'Siajo' is

small, astringent, of good quality and flavor; performs well

in Florida.

'Taber No. 23'

is round to oblate with flat apex; fairly small; skin is

dark-red, stippled. Begins to ripen in September in Florida.

'Yamato Hyakume'

is large, with red skin; has little tannin when seed

content is low; tends to growth-ring cracking; is a heavy bearer in

Florida.

'Yokono' is

large, orange-red, astringent, of good quality; bears well

but tends to shed fruit; keeps well.

Maru is a group name for several roundish types of Japanese persimmon

with brilliant orange-red skin, cinnamon-colored flesh; medium to small

in size; flesh is juicy, sweet, richly flavored; they have excellent

keeping quality after ripening, store and ship well and are very

decorative.

At the Pomological Station, Coonor, India, an unnamed type and a named

cultivar, 'Dai Dai Maru' have performed well. The unnamed cultivar is

broad at the base, large, attractive, deep-red, astringent until fully

ripe, then very sweet; bears well regularly. The tree is semi-erect.

'Dai Dai Maru'

has a broadly rounded apex, is of medium size;

orange-red, glossy, with a slight bloom; has dark flesh, is not edible

until fully cured; seedless unless cross-pollinated; bears good crops

regularly. The tree is of semi-erect habit.

In Brazil, cultivars are sorted into 3 groups. Group 1, 'Sibugaki',

includes those that are yellow-fleshed, always astringent whether

seedless or not ('Taubaté', 'Hachiya', 'Trakoukaki',

'Hatemya', etc.).

'Taubatá',

the most popular of this group, is round,

slightly flattened, large, yellow-fleshed, very astringent; highly

perishable, lasting only 3 to 4 days after ripening.

Group 2, 'Amagaki', includes those that are yellow-fleshed, never

astringent whether seedless or not ('Jiro', 'Tuyu', 'Hannagosho').

'Hannagosho'

is of excellent quality but in Florida is slow in losing

astringency and the tree is deficient in male flowers.

'Jiro' is

second to 'Fuyu' in importance in Japan; is of high quality

and ships well. The fruit is colorful and the tree vigorous in Florida.

Group 3, 'Variavel', or 'Variaveis', includes those that are astringent

when they have several seeds, and partially or totally non-astringent

when they have only one or a few seeds. The flesh is yellow when there

are no seeds and dark when seeds are present ('Rama Forte', 'Guiombo',

'Luiz de Queiroz', 'Hyakume', 'Chocolate', etc.).

'Guiombo'

(perhaps the same as 'Korean') is one of the best in Florida,

with thin skin; but it is a biennial bearer when young.

'Rama Forte',

the most popular of this group is oblate, medium to

large, with dark-yellow flesh, or dark-brown when there are many seeds;

keeps well–8 to 10 days at room temperature after ripening;

yields 30% more than 'Taubaté' and its branches are less apt

to break under a heavy crop.

The Instituto Agronomico do Estado de Sao Paulo has developed various

promising hybrids.

In 1922, seeds of 'Kai Sam T'sz' (chicken-heart persimmon) from Canton,

China, were sent to the United States Department of Agriculture as a

subtropical cultivar which might be appropriate for southern Florida

and the West Indies in contrast to the hardier types brought in from

Japan and northern and central China, but it seems to have soon dropped

out of sight.

Among commercial cultivars in Japan not already mentioned are:

'Suruga'

(distributed in 1959); orange-red, non-astringent, very sweet,

keeps well.

'Gosho',

orange-red, non-astringent, sweet, of high quality but giving

a low yield because of excessive shedding of immature fruits.

'Hiratanenashi',

oblate, somewhat 4-sided, astringent, thick-skinned;

seedless; of high quality, but keeps only a short time after curing;

mostly used for drying.

'Aizumishirazu',

rounded, astringent, black-spotted around seeds; of

fair quality; bears well.

'Yotsumizo',

small, astringent, usually seedless, sweet after curing;

bears well; often dried.

Of six cultivars tested in Queensland ('Tanenashi', 'Hyakume', 'Dai Dai

Maru', 'Tsuru Magri', 'Flat Seedless', and 'Nightingale'), all grafted

on D. lotus, only 'Nightingale' proved satisfactory in fruit quality

and yield in an assessment made after 3 years of fruiting.

'Nightingale'

is classed as PCA (pollination constant, astringent); is

conical, 3 1/2 in (9 cm) long; red; of distinctive flavor; with an

average of 2 1/2 seeds per fruit. The tree is semi-dwarf and fairly

precocious.

Pollination

Some cultivars in certain locations and under some conditions, will

fruit abundantly without cross-pollination, but this trait is not

dependable. In commercial groves, the cultivar known as 'Gailey', which

regularly produces many male flowers, is interplanted to insure

adequate pollination. The formula is one male for every 8 female trees,

uniformly dispersed throughout the grove; or 12 to 24 pollinating trees

per acre (30-60 per ha). Japanese farmers sometimes plant the

pollinating trees as a hedge around the grove. If hand-pollination of

early cultivars is necessary, unopened male buds are collected, dried,

opened and the pollen separated and stored. When needed, it is mixed

with skimmed milk or club moss (Lycopodium) and applied at 1/7 to 2/7

oz per acre (10-20 g per ha).

If the flowers are not effectively pollinated, the entire crop of fruit

may fall prematurely. This is a fault of the cultivar 'Isu' in Japan.

Losses can be reduced by girdling the tree after flowering but the

practice has the effect of retarding growth. If the weather is hot and

dry at blooming time, pollination will be inadequate and very few

fruits will be set. The maintenance of bee colonies (1 or 2 hives for

every 2 1/2 acres, or per ha) in persimmon orchards will enhance

pollination, especially in cultivar 'Fuyu'.

Climate

The Japanese persimmon needs a subtropical to mild-temperate climate.

It will not fruit in tropical lowlands. In Brazil, the tree is

considered suitable for all zones favorable to Citrus, but those zones

with the coldest winters induce the highest yields. The atmosphere may

range from semi-arid to one of high humidity.

Trees in the Middle Atlantic States have been known to have withstood

temperatures as low as 20° F (-6.67° C) and to have

remained in excellent condition and fruitful after 40 years.

Soil

The tree is not particular as to soil, and does well on any moderately

fertile land with deep friable subsoil. In Florida, a sandy loam with

clay subsoil promotes good growth. While the young tree needs plentiful

watering, good drainage is essential.

Propagation

Indonesians propagate the tree by means of root suckers. In the Orient,

selected cultivars are raised from seed or grafted onto wild rootstocks

of the same species, or onto the close relative, D. lotus L. In the

eastern United States, the trees are grafted onto the native American

persimmon, D. virginiana.

This rootstock significantly contributes to

cold-resistance.

California growers have found D.

kaki the most satisfactory rootstock,

D. lotus

rootstock resulting in much lower yields.

Seeds for the production of rootstocks need no pretreatment. They are

planted in seedbeds or directly in the nursery row 8 to 12 in (20-30

cm) apart with 3 to 3 1/2 ft (0.9-1.06 m) between the rows. After a

season of growth, they may be whip-grafted close to the surface of the

soil, using freshly cut scions or scions from dormant trees kept moist

in sphagnum moss.

Cleft-grafting is preferred on larger stock and for top-working old

trees. In India, cleft-grafting on stem has been 88.9% successful;

while cleft-grafting on crown and tongue-grafting on stem have been

73.4% successful when the grafted plants were left for 2 weeks at about

77° F (25° C) and relative humidity of 75% for 2

weeks before planting.

In the Kulu Valley, India, scions are grafted onto 2-year-old D. lotus

seedlings which are mounded with earth to

cover the graft until it

begins to sprout. At the Fruit Research Station, Kandaghat, 2-year-old

D. lotus seedlings were used as rootstock for veneer and

tongue grafts

from cv 'Hachiya' between late June and the third week of August.

Success rates ranged from 80 to 100%.

In Palestine, trees grafted on D.

lotus and grown on light soil are

dwarfish, fruit heavily at first, but are weak and short-lived. Those

grafted on D.

virginiana are larger and vigorous and bear heavily

consistently. The only disadvantage is that the shallow root system

fans out to 65 ft (20 m) from the base of the tree and wherever the

roots are injured by cultivation, suckers spring up and become a

nuisance.

Culture

The soil should be well prepared–deeply plowed and enriched

with organic matter. Trees should be set out at spacings ranging from

15 x 5 ft (4.5 x l.5 m) to 20 x 20 ft (6 x 6 m), depending on the habit

of the cultivar. In Japan, 404.7 plants per acre (1,000 per ha) may be

installed at the outset, to be thinned down to 85 trees per acre (200

per ha) in 10-15 years.

Good results have been obtained with a fertilizer mixture of 4 to 6% N,

8 to 10% P and 3 to 6% K at the rate of 1 lb (.45 kg) per tree per year

of age. Generally the application is made in spring, but some growers

apply half in the spring, half in July. Over-fertilization or excessive

amounts of nitrogen fertilizers will cause shedding of fruits.

Young trees are pruned back to 2 1/2 ft to 3 ft (.74-.91 m) when

planted and later the new shoots are thinned with a view to forming a

well-shaped tree. Some cultivars tend to develop a willowy growth and

require cutting back occasionally to avoid the development of weak

branches which break when heavy with fruit. Annual pruning during the

first 4 to 5 winters is desirable in some cultivars. If a tree tends to

overbear and shows signs of decline, it should be drastically cut back

to give it a fresh start.

After flowering, the trees should be irrigated every 3 weeks on light

soil, every month on heavier soil, until time for harvest. One

California grower, with trees on deep river loam, has provided furrow

irrigation every 2 weeks from April through September. Branches are

fragile and must be propped when heavily laden with fruits.

Cropping and Yield

Many cultivars begin to bear 3-4 years after planting out; others after

5-6 years. Shedding of many blossoms, immature and nearly mature fruits

is characteristic of the Japanese persimmon as well as the tendency

toward alternate bearing. The annual yield of a young tree ranges from

50 to 96 lbs (22.6-40.8 kg); of a full-grown tree, 330 to 550 lbs

(150-250 kg). Estimated yield in Brazil is 6.5 tons per acre (15 tons

per ha), but yields will vary with the cultivar and cultural practices.

Harvesting takes place in fall and early winter. Late ripening

cultivars may be picked after hard frosts or light-snowfall. Japan

produces about 300,000 tons per year.

Japanese growers use color charts to determine when each cultivar is

ready for harvest. Astringent cultivars are picked when fully mature

but hard and are cured before marketing.

Curing

In the Orient, much of the crop is left in piles covered by bamboo mats

to cure (near-freeze) naturally and is marketed throughout the winter.

In some parts of China, the fruit is cured in covered pits by

introducing the smoke from burning dung. There are several other

methods of curing: soaking in vinegar or immersing in boiling water and

letting stand for 12 hours. 'Hachiya' fruits kept in warm water

–104° F (40° C)–for 24 hours will

be firm and non-astringent 2 days after treatment. One practice is to

leave the astringent fruits in lime water for 2 days but tests have

shown no advantage of a lime solution over pure water except that lime

disinfects and can prevent the rotting that might follow soaking.

In Japan, the fruits may be sprayed with ethanol, or stored for 10 days

to 2 weeks in kegs which previously contained sake; or they may be

stored in air-tight containers with ethylene gas for 3 days. Carbon

dioxide is widely employed and the treatment consists of storing in a

95% CO2 atmosphere for 24 hours at 68° to 77° F

(20°-25° C), but the fruit softens very quickly

thereafter. In Brazil, successful curing has been achieved by immersing

'Taubate' persimmons in 1,000 ppm solution of ethephon (an ethylene

generator) for 1 hour and then storing at room temperature for 4 days.

Large quantities are cured by exposure to the fumes of alcohol

(aguardiente), acetylene gas from combustion of calcium carbonate, or

gas from burning sawdust, in hermetically sealed chambers at

temperatures between 68° and 82.4° F (20°

and 28° C) at relative humidity of 80%. Various other chemical

processes and gamma radiation have been successfully employed in other

countries.

A simple method was discovered in California some years ago. The newly

picked fruits were merely pierced once at the apex with a needle dipped

in alcohol, then the fruits were layered with straw in a tightly closed

box for 10 days. The homeowner may merely keep the fruits at room

temperature in a closed vessel or plastic bag for 2-4 days with

bananas, pears, tomatoes, apples, or other fruits which give off

ethylene gas. In India, the persimmons are individually paper-wrapped

and placed in alternate rows with 'Kieffer' pears in a closed container

and are edible in 3 days. Non-astringent cultivars need no curing.

Packing, Keeping Quality and Storage

In California, persimmons are graded by size, then tissue-wrapped and

packed in peach boxes for rail shipment in refrigerated cars. Packing

in other areas is similar. Astringent types soften in 2 or 3 days after

treatment and quickly become overripe. Non-astringent types are usually

harder than astringent types when picked, and they therefore ship and

keep better. Persimmons have been kept for 2 months at 30° F

(-1.11° C) and 85-90% relative humidity. 'Triumph' is

frequently stored in Israel for as long as 4 months at 30° F

(-1.11°C). Persimmons have been kept in good condition for

several months in sealed 0.06 mm polyethylene bags at 32° F

(0° C).

Spraying the bearing branches with gibberellic acid 3 days before

harvest has retarded maturity on the tree; has doubled the storage life

of astringent types after curing.

Pests and Diseases

In Brazil, premature fall of 'Fuyu' is partly linked to heavy

infestation by the mite, Aceria

diospyri. Spraying with Sevin 85 ppm 3

times at 30-day intervals right after petal fall controls the mite and

increases yield. Retithrips

syriacus feeds on and blemishes the leaves

and fruit skin in Palestine but has been controlled by spraying with

nicotine sulfate. The greenhouse thrips (Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis)

blemishes fruits in Queensland. San José scale is combatted

by a dormant application of Bordeaux in diesel emulsion in India. In

Florida, white peach scale, Pseudaulacaspis

pentagona, has required

control and a twig girdler, Onsideres

cingulatus, has been troublesome.

Also, a flat-headed borer drills into the bark and the wood causing

oozing of gum and decline in vigor. The main enemies in the eastern

United States are mealybugs which distort young shoots and kill all new

growth unless controlled. They do not seriously affect mature trees.

In Brazil and Queensland, fruit flies may attack the fruits, especially

in dry years. Tree-ripe persimmons are sought by all kinds of birds,

especially by parrots and crows in India, where flying foxes are a

nocturnal menace. The less astringent types seem to be preferred by all

of these predators. Bird-repellent sprays have given good control in

Queensland. There, sunburn affects marketability especially of

'Tanenashi' and 'Tsuru magri'.

In India, low germination rates of planted seeds has been traced to dry

rot caused by Penicillium

sp. It can be controlled by pretreatment with

an appropriate fungicide.

D. lotus

rootstock is subject to root rot and crown gall in Florida but

resistant to wilt caused by Cephalosporium

diospyri which induces

severe defoliation and has killed trees on D. virginiana

rootstock. In

Brazil, Cercospora

may spot the leaves, and a virus causes

"mosaic"–mottling of leaves and premature leaf fall, shedding

of flowers, and necrotic spots on fruits; also a different necrosis on

the tree and the bark of shoots, twigs and branches that causes

die-back. Anthracnose occurs on fruits that have slightly cracked or

have been pierced by insects. In Florida, leaf spot, algal leaf spot,

twig blight, twig dieback, root rot, thread blight and other fungal

diseases may occur.

Food Uses

Fully ripe Japanese persimmons are usually eaten out-of-hand or cut in

half and served with a spoon, preferably after chilling. Some people

prefer to add lemon juice or cream and a little sugar. The flesh may be

added to salads, blended with ice cream mix or yogurt, used in

pancakess, cakes, gingerbread, cookies, gelatin desserts, puddings,

mousse, or made into jam or marmalade. The pureed pulp can be blended

with cream cheese, orange juice, honey and a pinch of salt to make an

unusual dressing.

Ripe fruits can be frozen whole or pulped and frozen in the home

freezer. Large quantities of 'Tamopan' are preserved by drying. Drying

is commonly practiced in Brazil and the dried fruit is popular

throughout the country. Some California growers dry the 'Hachiya' by a

Chinese method. The fruits are picked when mature but firm, are peeled

and hung up by their stems for 30-50 days to dry in the sun. Kneading

every 4-5 days is necessary to give uniform texture and improve flavor.

Then they are taken down and sweated for 10 days in heaps under mats.

Sugar crystals form on the surface. Lastly, they are hung up again to

dry in the wind. In the Orient, the peelings are dried separately and

are mixed in with fruits when packed for sale. An inferior product is

made by slitting the skin with a knife, then spreading the fruits out

on mats to dry for several weeks, then sweating them in piles, and the

product is sold at a very low price.

In Indonesia, ripe fruits are stewed until soft, then pressed flat and

dried in the sun. Early travelers called such fruits "red figs".

Intestinal compaction from consumption of persimmons in Israel has been

eliminated by drying the fruits before marketing, and some dried fruits

are now being exported to Europe. Surplus persimmons may be converted

into molasses, cider, beer and wine. Roasted seeds have served as a

coffee substitute.

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion* |

| Calories |

77 |

| Moisture |

78.6 g |

| Protein |

0.7 g |

| Fat |

0.4 g |

| Carbohydrates |

19.6 g |

| Calcium |

6 mg |

| Phosphorus |

26 mg |

| Iron |

0.3 mg |

| Sodium |

6 mg |

| Potassium |

174 mg |

| Magnesium |

8 mg |

| Carotene |

2,710 I.U. |

| Thiamine |

0.03 mg |

| Riboflavin |

0.02 mg |

| Niacin |

0.1 mg |

| Ascorbic Acid |

11 mg |

| *Average values. |

|

The astringent substance in the persimmon, generally called "tannin",

has been much studied and variously defined as knowledge of tannins and

other phenols has unfolded. To put it simply, it is classed as a

condensed tannin (proanthocyanidin) of complex structure.

One would be wise to eat only fully ripe persimmons from which the

tannin has been almost entirely eliminated. The skin, which retains

some tannin, should not be eaten.

Other Uses

Tannin from unripe Japanese persimmons has

been employed in brewing

sake, also in dyeing and as a wood preservative. Juice of small,

inedible wild persimmons, crushed whole, calyx, seeds and all, is

diluted with water and painted on paper or cloth as an insect- and

moisture-repellent.

The wood of the tree is fairly hard and heavy, black with streaks of

orange-yellow, salmon, brown or gray; close-grained; takes a smooth

finish and is prized in Japan for fancy inlays, though it has an

unpleasant odor.

Medicinal Uses: A decoction of the calyx and fruit stem is sometimes

taken to relieve hiccups, coughs and labored respiration.

|

|