Article from

VSCNews, Vegetable and Specialty Crop News

by Tripti Vashisth and Mercy Olmstead

Hydrogen Cyanamide for

Low-Chill Peaches

in Florida

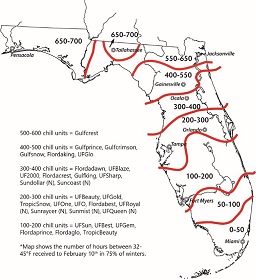

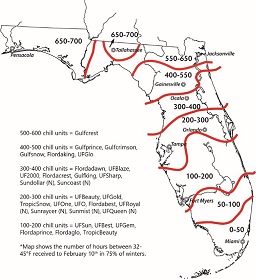

Fig. 1

Chill-unit accumulation in Florida (below 45 F through Feb. 10) with low-chill peach/nectarine (N) cultivar options.

Interest

in Florida peach production remains steady, with approximately 2,000

acres in the state. Florida peach growers have a number of advantages:

1)

Early flowering and fruit set result in the ability to harvest fruit

earlier in the domestic market window, yielding higher economic returns.

2)

Recent surveys show that consumers prefer local produce, making early

Florida peaches desirable in comparison to peaches imported from Latin

America.

3) Peach breeding programs led by University of Florida and

Texas A&M have resulted in a number of low-chill peach

varieties

which are suitable to be grown in the southeastern United States.

CHILL-UNIT

ACCUMULATION

Peach

trees are deciduous and enter dormancy. This means the trees shed their

leaves during the late fall and early winter. During this dormant

stage, a certain amount of cold weather (measured by accumulation of

chill units) is needed to resume normal growth in the spring.

Low-chill

peach varieties require fewer chill units compared to varieties grown

in more northern states, making them suitable for mild winter regions

of the Southeast. Therefore, selecting the right peach cultivar is very

important. Peach varieties that do not accumulate the required

chill-unit accumulation can result in poor or uneven budbreak, sporadic

flowering, delayed leaf emergence and poor fruit set. Figure 1 shows

the chill accumulation range in Florida and potential peach variety

options for those regions. Fawn.ifas.ufl.edu and Agroclimate.org are

the most common websites to monitor chill-unit accumulation in Florida.

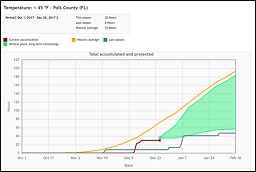

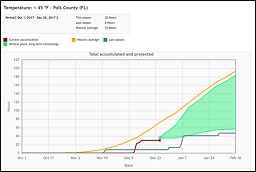

Fig. 2

Chill-unit accumulation for the current season, last season and the

historic average in Polk County, Florida. In 2016 (shown by turquoise

line), accumulated chill hours were less than 50 for the entire season.

The figure is directly adapted from

https://agroclimate.org/tools/Chill-Hours-Calculator.

There

are several models used to calculate the accumulated chill units. The

most common model, Weinberger (1950), adds the total number of hours

below 45 F during the fall and winter months. The range of time used

for chill-unit accumulation calculation takes into account the time

period from defoliation to first bud swell, which for Florida is

typically Oct. 1 to Feb. 10.

Even with several low-chill

varieties available to Florida growers, mild winter temperatures and

climate variability challenge Florida peach production. In 2016,

Central Florida accumulated less than 50 chill units by the end of

January (Figure 2), which is less than half of the historic average at

any given time. Mild winters interrupt the onset of dormancy and

chill-unit accumulation, causing extended bloom periods, non-uniform

flowering and leaf budbreak. Both extended bloom and non-uniform

budbreak can cause loss of marketable fruit and non-uniform ripening,

creating labor and economic challenges.

In growing areas with

low chill-unit accumulation, hydrogen cyanamide (HCN) has been used to

aid in the process of overcoming chill-unit requirements. Several

reports on grape, blueberry, kiwi, apple and peach indicate that when

inadequate chilling is received during the dormant season, the use of

HCN is effective in releasing dormancy and enhancing uniform budbreak.

HCN works best when a significant amount of chill units have already

accumulated. However, if applied after bud swell, phytotoxicity can

occur, damaging the flower buds.

TRIAL SEES

SUCCESS

In

order to ensure that HCN works well for low-chill peach cultivars under

Florida conditions, we set up a trial at the University of Florida

Plant Science Research and Education Unit in Citra (Marion County) with

the peach cultivar TropicBeauty. We applied HCN at a rate of 1.2

percent active ingredient and monitored the trees for floral and

vegetative growth.

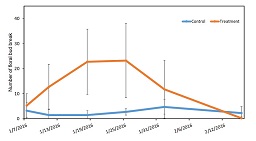

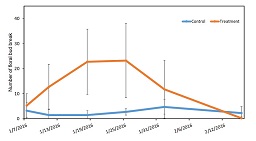

Trees treated with HCN broke bud

approximately one-month earlier than the control, and floral budbreak

was uniform and compressed (Figure 3). The fruit from HCN-treated trees

ripened uniformly and were of marketable quality. The overall yield was

higher from untreated (control) trees as there was a prolonged bloom

with fruit set throughout the spring; however, these fruits were of low

quality and unmarketable. Overall, this trial suggests that HCN can be

successfully used in Florida for uniform budbreak and to compensate for

insufficient chill units.

Fig. 3

Floral budbreak in hydrogen cyanamide- treated and untreated control

trees over 40 days after hydrogen cyanamide application in TropicBeauty

peach.

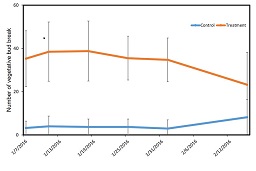

GETTING

APPLICATION TIMING RIGHT

When

using HCN as a management tool, it is critical to apply it at the right

time, as some amount of chill units are required for good efficacy.

Late application may result in phytotoxicity and can cause flower and

vegetative bud damage.

Pollen grain color has been initially

suggested as an indicator of when to apply HCN

(aces.edu/dept/peaches/chillcom20jan.html). Therefore, in our trial, we

monitored flower bud pollen grain color. We found pollen grains ranging

in color from translucent white to bright opaque yellow on the tree at

any given time in late December.

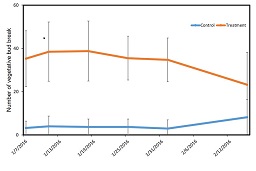

Fig. 4

Vegetative budbreak in hydrogen cyanamide-treated and untreated control

trees over 40 days after hydrogen cyanamide application in TropicBeauty

peach.

The

application was made when the majority of flower buds contained

translucent pollen grains. When pollen grains are translucent and not

opaque, HCN has been successfully applied with positive effects on

budbreak and uniform blooming. However, as the pollen grain color

changes to yellow, the application of HCN should be avoided as buds may

be too advanced in maturity.

HCN is highly toxic with severe

side effects if proper protection and caution is not exercised. Read

and follow the label carefully.

Tripti

Vashisth is an assistant professor at the University of Florida

Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Citrus Research and

Education Center in Lake Alfred. Mercy Olmstead is a former University

of Florida associate professor and Extension specialist.

|

|