| Avocado Pests | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back

to Avocado Page  Fig. 1 Adults and nymphs of the avocado lace bug Fig. 4 Dorsal view of male Platypus flavicornis Fabricius  Fig. 8  Redbay ambrosia beetles (Xyleborus glabratus): a) comparison of beetle to a penny; b) top view and c) side view of a single adult.  Fig. 13 Mite damage to fruit  Fig. 17 Dictyospermum scale Chrysomphalus dictyospermi (Morgan)  Fig. 20 Adult of an avocado mirid, Dagbertus fasciatus  Fig. 21  Adult redbanded thrips, Selenothrips rubrocinctus (Giard)  Fig. 24 Gold-dust Weevil Hypomeces squamosus (Fabricius, 1792)  Fig. 25 Avocado trunks damaged by tree girdler larvae  Fig. 26 Lateral view of a worker of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren.

| Minor

and occasional pests include ambrosia beetles, aphids, mealybugs,

avocado leafroller, avocado looper, banded cucumber beetle,

caterpillars, grasshoppers, and slugs/snails. Banded Cucumber Beetle, Diabrotica balteata LeConte, University of Florida pdf Avocado Lace Bug (Fig. 1) Pseudacysta Perseae (Heidemann) Insecta: Hemiptera: Tingidae The avocado lace bug was historically regarded as having a limited distribution throughout the Florida peninsula, causing little economic damage. However, the number of complaints about leaf damage resulting from this insect has increased recently. 3 The avocado lace bug inhabits the undersurface of leaves and feeds by penetrating the tissue with its piercing-sucking mouthparts and removing plant sap. The bug lives in colonies, depositing eggs upright in irregular clusters in the same area that the bug inhabits. The life cycle of the avocado lace bug is about three weeks. 3

Fig. 2. Eggs of the avocado lace bug Fig. 3. Lace bug damage on avocado leaf Further Reading Avocado Lace Bug, Pseudacysta perseae (Heidemann), University of Florida pdf Avocado Lace Bug, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources pdf Lace Bugs, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources pdf Ambrosia Beetle (Fig. 4) Platypus spp. Insecta: Coleoptera: Platypodidae The family Platypodidae includes approximately 1,000 species, most of which are found in the tropics (Schedl 1972). Seven species of platypodids, all in the genus Platypus, are found in the United States, four of which occur in Florida. All species found in Florida are borers of trunks and large branches of recently killed trees and and may cause economic damage to unmilled logs or standing dead timber. 2

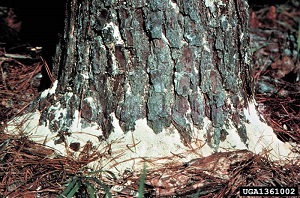

Fig. 5. Sawdust tube produced by an ambrosia beetle on a dead redbay. Multiple species of ambrosia beetles attack redbays killed by Xyleborus glabratus and its associated fungus. Fig. 6. Boring dust (stage 3) at base of tree resulting from feeding of the ambrosia beetle Platyus flavicornis Fabricius. Fig. 7. Redbay (Persea borbonia) trunk with ambrosia beetle sawdust (frass) tubes at points of entrance for adult beetles constructing galleries Further Reading Ambrosia Beetles, Platypus spp., University of Florida pdf A Guide to Florida's Common Bark and Ambrosia Beetles, University of Florida pdf Laurel Wilt (Fig. 8) Caused by the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle (Xyleborus glabratus) The redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus Eichhoff and its fungal symbiont, Raffaelea sp., are new introductions into the southeastern United States. Xyleborus glabratus was first detected in 2002 and is one of the 10 ambrosia beetle species in the US (Haack 2003, 2006). The beetle transmits the causal pathogen of laurel wilt disease among plants in the Laurel family (Lauraceae), which is caused by one of its fungal symbionts, Raffaelea lauricola (Mayfield and Thomas 2006, Fraedrich et al. 2009). The X. glabratus and R. lauricola complex is considered a "very high risk" invasive disease pest complex having potential equal to that of Dutch elm disease or chestnut blight (Global Invasive Species Database 2010). Laurel wilt is a relatively new disease and much is still unknown about how it will impact the flora of North America. 5

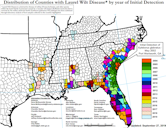

Fig. 9. Avocado trees infected with laurel wilt disease. Trees can die just 6 to 8 weeks after infection. Fig. 10. Redbay with partially wilted crown Fig. 11. Same tree eight months later Fig. 12. Distribution of laurel wilt disease in the United States as of 2019

Further Reading Laurel Wilt, Avocado Diseases Mites (Fig. 13) Oligonychus yothersi, O. punicae, Tegolophus perseaflotae Spider mites of the genus Oligonychus commonly infest avocados in Florida. Feeding is first confined to the upper leaf surface along the midrib and then spreads along secondary veins. the areas along the veins become reddish-brown. Damage by the spider mites is commonly observed from October through February, causing a reduction in photosynthesis of up to 30 percent. Infested leaves often abscise prematurely. Control measures are often started when mite pressures reach six or more mites per leaf. For spider mites in general, life cycles may range from 5 to 20 days. Lifespan of the spider mite may be as long as one month. The female lays several hundred eggs over a lifetime. The eggs are capable of overwintering within the grove. 3 Avocado bud mite (T. perseaflorae) populations start to increase from March to May. These mites are found on buds and on developing fruit. The feeding of the avocado bud mite causes necrotic spots and irregular openings in apical leaves and may cause fruit deformation and discoloration. 3

Fig. 14,15. Damage to avocado leaves Fig. 16. Damage on fruit

Scales (Fig. 17) Chrysomphalus dictyospermi, C. aonidum, Ceroplastes floridensis, Hemiberlesia lataniae, Protopulvinaria pyriformis Scale insects can be of two types, armored scales or soft scales. Armored scales are protected by a distinct, hard, separable shell. Soft scales have a delicate body not protected by a shell and often produce honeydew. Soft and armored scales are plant-feeding insects, often controlled by natural and released parasites, predators, and pathogens. In cases when the natural balance of predation has been disrupted, scale populations may increase to levels requiring chemical treatment. Since scale insects are relatively immobile, and at least one month is required for the scale-insect egg to reach the adult stage, an infestation builds up slowly (in comparison to mites or aphids) and may be hard to spot. It is important to verify that the scale insects attached to the plant are alive, as mummies accumulate on the plant over time. 3

Fig. 18. Florida wax Scale - C. floridensis Comstock Fig. 19. Florida red scale C. aonidum (Linnaeus) Mirids (Fig. 20) Daghbertus fasciatus, D. olivaceous, Rhinacloa sp. These sucking insects are small (3 mm) and vary in color from green to brown. They are prevalent during the avocado-flowering months, January through April. The flower and early fruit feeding by mirids may cause the fruit to drop. Wounds created by the mirids serve as entry points for decay organisms. The insects also lay eggs on opening buds, leaves, flowers, and small fruit. 3 Redbanded thrips (Fig. 21) Selenothrips rubrocinctus (Giard) Insects: Thysanoptera: Thripidae The redbanded thrips is ubiquitous throughout Florida, but the pest is generally found in damaging numbers from Orlando to Key West. Female redbanded thrips are slightly greater than 1 mm in length with a dark-brown to black body underlain by red pigment, chiefly in the first three abdominal segments. The larvae is light yellow to orange with the first three and last segments of the abdomen bright red. The life cycle of this thrips is about three weeks in Florida, and several generations are possible each year. Infestations of redbanded thrips may cause leaf drop, at times totally denuding trees. 3 The larvae and adults feed on the foliage and the fruit by piercing the epidermis with their mouthparts. Redbanded thrips prefer young foliage and their feeding causes distortion and drop. The thrips destroys the cells on which it feeds, causes injury to the fruit, and leaves unsightly dark colored droplets or blotches of excrement on the leaf surface. A more serious injury is leaf drop, which may denude trees. Honeydew excretory products from red-banded thrips and other insect infestations fall to leaves, fruits or objects beneath, giving rise to the objectionable, fruit-degrading black sooty mold. 4

Fig. 22. Adults and larvae Fig. 23. Pupa(e) Further Reading Redbanded Thrips, Selenothrips rubrocinctus (Giard), University of Florida pdf Tree Girdler (Fig. 24, 25) Heilipus squamosus Insect: Coleoptera: Curculionidae This weevil is one of the most potentially damaging pests of avocado. The adult weevil is about 1.2 cm in length, predominantly black in color with irregular white areas and spots on the wing covers. Eggs are deposited in the inner bark, near ground level. As the larvae feed, they burrow in the inner bark or in the wood of small trees. Reddish-brown frass extruding from burrowing holes is a sign of infestation. Young trees 2 – 4 years old may be girdled so completely that the trees die. Adult weevils feed on avocado buds, twigs, and blossoms, as well as on young fruit after it has emerged. 3 Red Imported Fire Ants (Fig. 26) Solenopsis invicta Buren Insect: Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae Two species of fire ants are found in Florida. Most notorious is Solenopsis invicta Buren, the red imported fire ant (RIFA), followed by the much less common S. geminata (Fabricius), the tropical or native fire ant. Other more common U.S. members of this genus include S. xyloni McCook, the southern fire ant; S. aurea Wheeler, found in western states; and S. richteri Forel, the black imported fire ant, confined to northeastern Mississippi and northwestern Alabama. 6

Fig. 27. Typical colony of the red imported fire ant, S. invicta Buren. Fig. 28. Mound of the red imported fire ant, S. invicta Buren, in St. Augustinegrass. Further Reading Red Imported Fire Ant Solenopsis invicta Buren, University of Florida pdf Managing Imported Fire Ants in Urban Areas, University of Florida pdf Further Reading Florida Integrated Pest Management, University of Florida ext. link List of Avocado Pests, University of Florida TREC ext. link | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bibliography 1 Mead, F. W. and J. E. Pena. "Avocado Lace Bug, Pseudacysta Perseae (Heidemann), (Insecta Hemiptera: Tingidae)." Entomology and Nematology Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, Original Pub. July 1998, Revised Apr. 2016, Reviewed Feb. 2019, EENY-039,UF/IFAS Extension edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in166. Accessed 14 Apr. 2017, 17 Sept. 2019. 2 Atkinson, T. H. "Ambrosia Beetle Platypus spp. (Insecta: Coleoptera: Platypodidae)."Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida, IFAS Extension, Original Pub. Nov. 2000, Revised July 2014 and Mar. 2021, EENY174, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in331. Accessed 18 Nov. 2013, 17 Sept. 2019, 5 Jan. 2024. 3 Mossler, Mark A., and Jonathan H. Crane. "Florida Crop/Pest Management Profile: Avocado." Pesticide Information Office, Horticultural Sciences Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, Sept. 2001, Reviewed Mar. 2012, Archived, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 7 Mar. 2015, 17 Sept. 2019. 4 Denmark, H. A., and D. O. Wolfenbarge. "Redbanded thrips Selenothrips rubrocinctus (Giard)." Entomology and Nematology Dept., University of Florida, IFAS Extension, EENY-099, Original Pub. June 1999, Revised Feb. 2019 and June 2022, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu./in256. Accessed 26 Apr. 2017, 17 Sept. 2019, 5 Jan. 2024. 5 Crane, Jonathan H., et al. "Recommendations for the Detection and Mitigation of Laurel Wilt Disease in Avocado and Related Tree Species in the Home Landscape." Horticultural Sciences Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, HS1358, Original pub. Feb. 2020, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs1358. Accessed 1 May 2020. 6 Collins, Laura, and Rudolf H. Scheffrahn."Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae)." Entomology and Nematology Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, IN352, Original Pub. Jan. 2001, Revises Aug. 2008 and Nov. 2013, Reviewed May 2020, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN352. Accessed 26 Apr. 2017. Video v1 "Laurel Wilt in Florida, Slowing the Spread." Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, www.fdacs.gov/Agriculture-Industry/Pests-and-Diseases/Plant-Pests-and-Diseases/Laurel-Wilt-Disease. Accessed 1 May 2020. v2 Crane, Johathan H. and Ian Maguire. "Cultural practices for the avocado." University of Florida, IFAS/TREC. Photographs Fig. 1,3 Castner, James. "Adults and nymphs of the avocado lace bug, Pseudacysta Perseae (Heidemann) and Leaf damage caused by the lace bug, Pseudacysta Perseae (Heidemann)." University of Florida, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 16 Nov. 2013. Fig. 2 Hunsberger, Adrian. "Eggs of the avocado lace bug, Pseudacysta Perseae (Heidemann)." University of Florida, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 16 Nov. 2013. Fig. 4 Almquist, David T. "Dorsal view of male Platypus flavicornis Fabricius." University of Florida, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 17 Nov. 2013. Fig. 5 Mayfield, Albert. "Small strings of compacted sawdust protrude from small bore holes along the trunk of a tree." Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Service, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 19 Nov. 2013. Fig. 6 Billings, Ronald F. "Boring dust (stage 3) at base of tree resulting from feeding of the ambrosia beetle Platyus flavicornis Fabricius." Texas Forest Service, 2005, Bugwood.org, bugwood.org. Accessed 18 Nov. 2013. Fig. 7 Billings, Ronald, F. "Redbay (Persea borbonia) trunk with ambrosia beetle sawdust (frass) tubes at points of entrance for adult beetles constructing galleries." Texas Forest Service, College Station, TX, 2010, Bugwood.org, bugwood.org. Accessed 6 Feb. 2014. Fig. 8 Thomas, Michael C. "Redbay ambrosia beetles (Xyleborus glabratus): a) comparison of beetle to a penny; b) top view and c) side view of a single adult." Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, edis.ifas.ufl.edu.Accessed 19 Nov. 2013. Fig. 9 Kendra, Paul. "Avocado trees infected with laurel wilt disease. Trees can die just 6 to 8 weeks after infection." USDA Agricultural Research Service, Tropical Plant Genetic Resources and Disease Research (TPGRDR) unit at the Pacific Basin Agricultural Research Center (PBARC), Hilo, HI. no. D3703-1, USDA/ARS, www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/nov16/d3703-1/ Accessed 1 May 2020. Fig. 10,11 Mayfield III, Albert E. Wilt symptoms of redbay attacked by Xyleborus glabratus and infected with Raffaelea lauricola. 2006. freshfromflorida.com. Florida Division of Forestry and M. C. Thomas, FDACS/DPI. Accessed 9 Feb. 2014. Fig. 12 "Distribution of laurel wilt disease in the United States as of 2019." US Forest Service, 11 Dec. 2019, USDA, www.fs.usda.gov/main/r8/forest-grasslandhealth. Accessed 1 May 2020. Fig. 13 Nelson, Scot. "Mite Damage to Avocado Fruit." N.d. hawaiiplantdiseases.net. Accessed 9 Feb. 2014. Fig. 14,15 Nelson, Scot. "Mite Damage to Avocado Leaves." N.d. hawaiiplantdiseases.net. Accessed 9 Feb. 2014. Fig. 17 Olsen, Charles. "Dictyospermum scale Chrysomphalus dictyospermi (Morgan)." USDA APHIS PPQ, 2012, Bugwood.org, bugwood.org. Accessed 7 Mar. 2015. Fig. 18 "Florida Wax Scale - Ceroplastes floridensis Comstock." United States National Collection of Scale Insects Photographs Archive, USDA ARS, 2006, Bugwood.org, bugwood.org. Accessed 7 Mar. 2015. Fig. 19 Graney, Lorraine. "Florida red scale Chrysomphalus aonidum (Linnaeus)." Bartlett Tree Experts, 2010, Bugwood.org, bugwood.org. Accessed 7 Mar. 2015. Fig. 20 Peña, Jorge E. "Adult of an avocado mirid, Dagbertus fasciatus." UF/IFAS - Tropical Research & Education Center, trec.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 18 Nov. 2013. Fig. 21,22,23 Buss, Lyle. "Adult redbanded thrips, Selenothrips rubrocinctus (Giard)." University of Florida 2010, Bugwood.org, bugwood.org. Accessed 19 Nov. 2013. Fig. 24 Dell, Johnny N. "Avocado Weevil, Heilipus apiatus (Olivier 1807)." University of Georgia, 2010, Bugwood.org, bugwood.org. Accessed 10 Feb. 2014. Fig. 25 Peña, Jorge E. "Avocado trunks damaged by tree girdler larvae." UF/IFAS - Tropical Research & Education Center, trec.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 18 Nov. 2013. Fig. 26 Almquist, David. "Lateral view of a worker of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren." University of Florida, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 10 Feb. 2014. Fig. 27 Porter, Sanford D. "Typical colony of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren." USDA, Gainesville, FL, ars.usda.gov. Accessed 10 Feb. 2014. Fig. 28 Scheffrahn, Rudolf. "Mound of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren, in St. Augustinegrass." University of Florida, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 10 Feb. 2014. Published 16 Nov. 2013 LR. Last update 5 Jan. 2024 LR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||