Brief Summary from

the Encyclopedia of Life

by Leo Shapiro

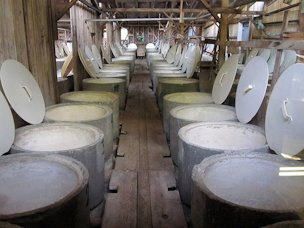

Traditional fermentation and curing of Olives

An olive vat room used for curing at Graber Olive House

Raw or fresh olives are naturally very bitter; to make them

palatable, olives must be cured and fermented, thereby removing

oleuropein, a bitter phenolic compound that can reach levels of 14% of

dry matter in young olives. In addition to oleuropein, other phenolic

compounds render freshly picked olives unpalatable and must also be

removed or lowered in quantity through curing and fermentation.

Generally speaking, phenolics reach their peak in young fruit and are

converted as the fruit matures. Once ripening occurs, the levels of

phenolics sharply decline through their conversion to other organic

products which render some cultivars edible immediately. One example of

an edible olive native to the island of Thasos is the throubes black olive, which when allowed to ripen in sun, shrivel, and fall from the tree, is edible.

The

curing process may take from a few days, with lye, to a few months with

brine or salt packing. With the exception of California style and

salt-cured olives, all methods of curing involve a major fermentation

involving bacteria and yeast that is of equal importance to the final

table olive product. Traditional cures, using the natural microflora on

the fruit to induce fermentation, lead to two important outcomes: the

leaching out and breakdown of oleuropein and other unpalatable phenolic

compounds, and the generation of favourable metabolites from bacteria

and yeast, such as organic acids, probiotics, glycerol, and esters,

which affect the sensory properties of the final table olives. Mixed

bacterial/yeast olive fermentations may have probiotic qualities.

Lactic acid is the most important metabolite, as it lowers the pH,

acting as a natural preservative against the growth of unwanted

pathogenic species. The result is table olives which can be stored

without refrigeration. Fermentations dominated by lactic acid bacteria

are, therefore, the most suitable method of curing olives.

Yeast-dominated fermentations produce a different suite of metabolites

which provide poorer preservation, so they are corrected with an acid

such as citric acid in the final processing stage to provide microbial

stability.

The many types of preparations for table olives

depend on local tastes and traditions. The most important commercial

examples are:

Spanish or Sevillian type

(olives with fermentation): Most commonly applied to green olive

preparation, around 60% of all the world's table olives are produced

with this method. Olives are soaked in lye (dilute NaOH, 2–4%) for 8–10

hours to hydrolyse the oleuropein. They are usually considered

"treated" when the lye has penetrated two-thirds of the way into the

fruit. They are then washed once or several times in water to remove

the caustic solution and transferred to fermenting vessels full of

brine at typical concentrations of 8–12% NaCl. The brine is changed on

a regular basis to help remove the phenolic compounds. Fermentation is

carried out by the natural microbiota present on the olives that

survive the lye treatment process. Many organisms are involved, usually

reflecting the local conditions or "Terroir" of the olives. During a

typical fermentation gram-negative enterobacteria flourish in small

numbers at first, but are rapidly outgrown by lactic acid bacteria

species such as Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus brevis and Pediococcus damnosus.

These bacteria produce lactic acid to help lower the pH of the brine

and therefore stabilize the product against unwanted pathogenic

species. A diversity of yeasts then accumulate in sufficient numbers to

help complete the fermentation alongside the lactic acid bacteria.

Yeasts commonly mentioned include the teleomorphs Pichia anomala, Pichia membranifaciens, Debaryomyces hansenii and Kluyveromyces marxianus. Once fermented, the olives are placed in fresh brine and acid corrected, to be ready for market.

Sicilian or Greek type

(olives with fermentation): Applied to green, semiripe and ripe olives,

they are almost identical to the Spanish type fermentation process, but

the lye treatment process is skipped and the olives are placed directly

in fermentation vessels full of brine (8–12% NaCl). The brine is

changed on a regular basis to help remove the phenolic compounds. As

the caustic treatment is avoided, lactic acid bacteria are only present

in similar numbers to yeast and appear to be outcompeted by the

abundant yeasts found on untreated olives. As very little acid is

produced by the yeast fermentation, lactic, acetic, or citric acid is

often added to the fermentation stage to stabilize the process.

Picholine or directly-brined type

(olives with fermentation): Applied to green, semiripe, or ripe olives,

they are soaked in lye typically for longer periods than Spanish style

(e.g. 10–72 hours) until the solution has penetrated three-quarters of

the way into the fruit. They are then washed and immediately brined and

acid corrected with citric acid to achieve microbial stability.

Fermentation still occurs carried out by acidogenic yeast and bacteria,

but is more subdued than other methods. The brine is changed on a

regular basis to help remove the phenolic compounds and a series of

progressively stronger concentrations of salt are added until the

product is fully stabilized and ready to be eaten.

Water-cured type

(olives with fermentation): Applied to green, semiripe, or ripe olives,

these are soaked in water or weak brine and this solution is changed on

a daily basis for 10–14 days. The oleuropein is naturally dissolved and

leached into the water and removed during a continual soak-wash cycle.

Fermentation takes place during the water treatment stage and involves

a mixed yeast/bacteria ecosystem. Sometimes, the olives are lightly

cracked with a hammer or a stone to trigger fermentation and speed up

the fermentation process. Once debittered, the olives are brined to

concentrations of 8–12% NaCl and acid corrected, and are then ready to

eat.

Salt-cured type

(olives with minor fermentation): Applied only to ripe olives, they are

usually produced in Morocco, Turkey, and other eastern Mediterranean

countries. Once picked, the olives are vigorously washed and packed in

alternating layers with salt. The high concentrations of salt draw the

moisture out of olives, dehydrating and shriveling them until they look

somewhat analogous to a raisin. Once packed in salt, fermentation is

minimal and only initiated by the most halophilic yeast species such as

Debaryomyces hansenii. Once cured, they are sold in their natural state

without any additives. So-called Oil-cured olives are cured in salt,

and then soaked in oil.

California or "artificial ripening" type

(olives without fermentation): Applied to green and semiripe olives,

they are placed in lye and soaked. Upon their removal, they are washed

in water injected with compressed air. This process is repeated several

times until both oxygen and lye have soaked through to the pit. The

repeated, saturated exposure to air oxidises the skin and flesh of the

fruit, turning it black in an artificial process that mimics natural

ripening. Once fully oxidised or "blackened", they are brined and acid

corrected and are then ready for eating.

|

© Leo Shapiro

|