From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Cape Gooseberry

Physalis peruviana L.

Physalis edulis Sims

ANACARDIACEAE

The genus Physalis, of the

family Solanaceae, includes annual and perennial herbs bearing globular

fruits, each enclosed in a bladderlike husk which becomes papery on

maturity. Of the more than 70 species, only a very few are of economic

value. One is the strawberry tomato, husk tomato or ground cherry, P. Pruinosa

L., grown for its small yellow fruits used for sauce, pies and

preserves in mild-temperate climates. Though more popular with former

generations than at present, it is still offered by seedsmen. Various

species of Physalis have been

subject to much confusion in literature and in the trade. A species

which bears a superior fruit and has become widely known is the cape

gooseberry, P. peruviana L. (P. edulis

Sims). It has many colloquial names in Latin America: capuli,

aguaymanto, tomate sylvestre, or uchuba, in Peru; capuli or motojobobo

embolsado in Bolivia; uvilla in Ecuador; uvilla, uchuva, vejigón or

guchavo in Colombia; topotopo, or chuchuva in Venezuela; capuli, amor

en bolsa, or bolsa de amor, in Chile; cereza del Peru in Mexico. It is

called cape gooseberry, golden berry, pompelmoes or apelliefie in South

Africa; alkekengi or coqueret in Gabon; lobolobohan in the Philippines;

teparee, tiparee, makowi, etc., in India; cape gooseberry or poha in

Hawaii.

Description

This

herbaceous or soft-wooded, perennial plant usually reaches 2 to 3 ft

(1.6-0.9 m) in height but occasionally may attain 6 ft (1.8) m. It has

ribbed, often purplish, spreading branches, and nearly opposite,

velvety, heart-shaped, pointed, randomly-toothed leaves 2 3/8 to 6 in

(6-15 cm) long and 1 1/2 to 4 in (4-10 cm) wide, and, in the leaf

axils, bell-shaped, nodding flowers to 3/4 in (2 cm) wide, yellow with

5 dark purple-brown spots in the throat, and cupped by a

purplish-green, hairy, 5-pointed calyx. After the flower falls, the

calyx expands, ultimately forming a straw-colored husk much larger than

the fruit it encloses. The berry is globose, 1/2 to 3/4 in (1.25-2 cm)

wide, with smooth, glossy, orange-yellow skin and juicy pulp containing

numerous very small yellowish seeds. When fully ripe, the fruit is

sweet but with a pleasing grape-like tang. The husk is bitter and

inedible.

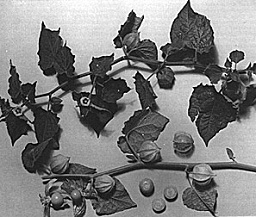

| | Fig.

114: The golden cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana) keeps well and

makes excellent preserves. The canned fruits have been exported from

South Africa and the jam from England. |

Origin and

Distribution

Reportedly

native to Peru and Chile, where the fruits are casually eaten and

occasionally sold in markets but the plant is still not an important

crop, it has been widely introduced into cultivation in other tropical,

subtropical and even temperate areas. It is said to succeed wherever

tomatoes can be grown. The plant was grown by early settlers at the

Cape of Good Hope before 1807. In South Africa it is commercially

cultivated and common as an escape and the jam and canned whole fruits

are staple commodities, often exported. It is cultivated and

naturalized on a small scale in Gabon and other parts of Central Africa.

| | Fig. 115: The cape gooseberry is a useful small fruit crop for the home garden; is labor-intensive in commercial plantings. |

Soon

after its adoption in the Cape of Good Hope it was carried to Australia

and there acquired its common English name. It was one of the few fresh

fruits of the early settlers in New South Wales. There it has long been

grown on a large scale and is abundantly naturalized, as it is also in

Queensland, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and Northern

Tasmania. It was welcomed in New Zealand where it is said that "the

housewife is sometimes embarrassed by the quantity of berries [cape

gooseberries] in the garden," and government agencies actively promote

increased culinary use.

In China, India and Malaya, the cape

gooseberry is commonly grown but on a lesser scale. In India, it is

often interplanted with vegetables. It is naturalized on the island of

Luzon in the Philippines. Seeds were taken to Hawaii before 1825 and

the plant is naturalized on all the islands at medium and somewhat

higher elevations. It was at one time extensively cultivated in Hawaii.

By 1966, commercial culture had nearly disappeared and processors had

to buy the fruit from backyard growers at high prices. It is widespread

as an exotic weed in the South Sea Islands but not seriously

cultivated. The first seeds were planted in Israel in 1933. The plants

grew and bore very well in cultivation and soon spread as escapes, but

the fruit did not appeal to consumers, either fresh or preserved, and

promotional efforts ceased.

In England, the cape gooseberry was

first reported in 1774. Since that time, it has been grown there in a

small way in home gardens, and after World War II was canned

commercially to a limited extent. Despite this background, early in

1952, the Stanford Nursery, of Sussex, announced the "Cape Gooseberry,

the wonderful new fruit, especially developed in Britain by Richard I.

Cahn." Concurrently, jars of cape goosebery jam from England appeared

in South Florida markets and the product was found to be attractive and

delicious. It is surprising that this useful little fruit has received

so little attention in the United States in view of its having been

reported on with enthusiasm by the late Dr. David Fairchild in his

well-loved book, The World Was My Garden. He there tells of its

fruiting "enormously" in the garden of his home, "In The Woods", in

Maryland, and of the cook's putting up over a hundred jars of what he

called "Inca Conserve" which "met with universal favor." It is also

remarkable that it is so little known in the Caribbean islands, though

naturalized plants were growing profusely along roadsides in the Blue

Mountains of Jamaica before 1913.

With a view to encouraging

cape gooseberry culture in Florida, the Bahamas, and the West Indies,

seeds have been repeatedly purchased from the Stanford Nursery and

distributed for trial. Good crops have been obtained. Nevertheless

there was no incentive to make further plantings.

Pollination

In

England, growers shake the flowers gently in summer to improve

distribution of the pollen, or they will give the plants a very light

spraying with water.

Climate

The

cape gooseberry is an annual in temperate regions and a perennial in

the tropics. In Venezuela, it grows wild in the Andes and the coastal

range between 2,500 and 10,000 ft (800-3,000 m). It grows wild in

Hawaii at 1,000 to 8,000 ft (300-2,400 m). In northern India, it is not

possible to cultivate it above 4,000 ft (1,200 m), but in South India

it thrives up to 6,000 ft (1,800 m).

In England, the plants have

been undamaged by 3 degrees of frost. In South Africa, plants have been

killed to the ground and failed to recover after a temperature drop to

30.5º F (-0.75º C).

The plant needs full sun but protection from

strong winds; plenty of rain throughout its growing season, very little

when the fruits are maturing.

Soil

The

cape gooseberry will grow in any well-drained soil but does best on

sandy to gravelly loam. On highly fertile alluvial soil, there is much

vegetative growth and the fruits fail to color properly. Very good

crops are obtained on rather poor sandy ground. Where drainage is a

problem, the plantings should be on gentle slopes or the rows should be

mounded. The plants become dormant in drought.

Propagation

The

plant is widely grown from seed. There are 5,000 to 8,000 seeds to the

ounce (28 g) and, since germination rate is low, this amount is needed

to raise enough plants for an acre–2 1/2 oz (70 g) for a hectare. In

India, the seeds are mixed with wood ash or pulverized soil for uniform

sowing.

Sometimes propagation is done by means of 1-year-old

stem cuttings treated with hormones to promote rooting, and 37.7%

success has been achieved. The plants thus grown flower early and yield

well but are less vigorous than seedlings. Air-layering is also

successful but not often practiced.

Culture

It

is necessary to determine the time of planting for each area. In India,

seeds are broadcast from March through May. In Hong Kong, planting in

seedbeds is done in September/October and again in March/April. In the

Bahamas the first seeds planted in late summer of 1952 produced healthy

plants and a continuous crop of fruits for 3 months during the

following winter. Additional seeds procured from England were planted

in April of 1953. The plants started to blossom in mid-July and from

September on continued to flower and set fruit, although no fruits

remained on the plants to maturity until the cooler months of winter

when a good yield was obtained. Seeds were again planted the following

November. Thirteen weeks later, the first fruits were ripening, and by

mid-May of the following year a heavy crop was harvested. In late June,

the plants were still growing and flowering profusely but only a few

fruits were being set and these failed to develop to maturity. This

condition continued into September, by which time some of the more

robust plants had reached 6 ft (1.8 in) in height with much lateral

growth.

In Jamaica, the initial planting of cape gooseberries in

late January of 1954 made slow growth until June when development

accelerated. By mid-August the plants had reached 15 in (37.5 cm) in

height with much lateral growth, and were flowering and setting fruit.

It would appear that the heat of summer is unfavorable for fruit

development and, therefore, the best time to plant the cape gooseberry

is in the fall so that fruit can be set during the cooler weather and

harvested in late spring or early summer. In California, the plants do

not fruit heavily until the second year unless started early in

greenhouses.

Some growers have kept plants in production for as

long as 4 years by cutting back after each harvest, but these plants

have been found more susceptible to pests and diseases.

In

India, plants 6 to 8 in (15-20 cm) high are set out 18 in (45 cm) apart

in rows 3 ft (0.9 m) apart. Farmers in South Africa space the plants 2

to 3 ft (0.6-0.9 m) apart in rows 4 to 6 ft (1.2-1.8 m) or even 8 ft

(2.4 m) apart in very rich soil. They apply 200 to 400 lbs (90-180 kg)

of complete fertilizer per acre (approx. = kg/ha) on sandy loam. Foliar

spraying of 1% potassium chloride solution before and just after

blooming enhances fruit quality.

In dry seasons, irrigation is necessary to keep the cape gooseberry plant in production.

Season

In

parts of India, the fruits ripen in February, but, in the South, the

main crop extends from January to May. In Central and southern Africa,

the crop extends from the beginning of April to the end of June. In

England, plants from seeds sown in spring begin to fruit in August and

continue until there is a strong frost.

Harvesting and Yield

In

rainy or dewy weather, the fruit is not picked until the plants are

dry. Berries that are already wet need to be lightly dried in the sun.

The fruits are usually picked from the plants by hand every 2 to 3

weeks, although some growers prefer to shake the plants and gather the

fallen fruits from the ground in order to obtain those of more uniform

maturity. At the peak of the season, a worker can pick 2 1/2 bushels

(90 liters) a day, but at the beginning and end of the season, when the

crop is light, only 1/2 bushel (18 liters).

A single plant may

yield 300 fruits. Seedlings set 1,800 to 2,150 to the acre (228-900/ha)

yield approximately 3,000 lbs of fruit per acre (approx. = kg/ha). The

fruits are usually dehusked before delivery to markets or processors.

Manual workers can produce only 10 to 12 lbs. (4.5-5.5 kg) of husked

fruits per hour. Therefore, a mechanical husker, 4 to 5 times more

efficient, has been designed at the University of Hawaii.

Keeping Quality

Cape

gooseberries are long-lasting. The fresh fruits can be stored in a

scaled container and kept in a dry atmosphere for several months. They

will still be in good condition. If the fresh fruits are to be shipped,

it is best to leave the husk on for protection.

Pests and Diseases

In

South Africa, the most important of the many insect pests that attack

the cape gooseberry are cutworms, in seedbeds; red spider after plants

have been established in the field; the potato tuber moth if the cape

gooseberry is in the vicinity of potato fields. Hares damage young

plants and birds (francolins) devour the fruits if not repelled. In

India, mites may cause defoliation. In Jamaica, the leaves were

suddenly riddled by what were apparently flea beetles of the family

Chrysomelidae. In the Bahamas, whitefly attacks on the very young

plants and flea beetles on the flowering plants required control.

In

South Africa, the most troublesome diseases are powdery mildew and soft

brown scale. The plants are prone to root rots and viruses if on

poorly-drained soil or if carried over to a second year. Therefore,

farmers favor biennial plantings. Bacterial leaf spot (Xanthomonas spp.) occurs in Queensland. A strain of tobacco mosaic may affect plants in India.

Food Uses

In

addition to being canned whole and preserved as jam, the cape

gooseberry is made into sauce, used in pies, puddings, chutneys and ice

cream, and eaten fresh in fruit salads and fruit cocktails. In

Colombia, the fruits are stewed with honey and eaten as dessert. The

British use the husk as a handle for dipping the fruit in icing.

Food Value Per 100 g of Edible Portion*

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion* |

| Moisture

|

78.9 g |

| Protein |

0.054 g |

| Fat |

0.16 g |

| Fiber |

4.9 g |

| Ash |

1.01 g |

| Calcium |

8.0 mg |

| Phosphorus |

55.3 mg |

Iron

|

1.3 mg |

| Carotene |

1.613 mg |

| Thiamine |

1.01 mg |

| Riboflavin | 0.032 mg | | Niacin | 1.73 mg | | Ascorbic Acid | 43.3 mg |

| *According

to analyses of husked fruits made in Ecuador. |

|

The ripe fruits are considered a good source of Vitamin P and are rich in pectin.

Toxicity

Unripe fruits are poisonous. The plant is believed to have caused illness and death in cattle in Australia.

Other Uses

Fruits: In the 18th Century, the fruits were perfumed and worn for adornment by native women in Peru.

Medicinal Uses:

In Colombia, the leaf decoction is taken as a diuretic and

antiasthmatic. In South Africa, the heated leaves are applied as

poultices on inflammations and the Zulus administer the leaf infusion

as an enema to relieve abdominal ailments in children.

Indian chemists have isolated from the leaves a minor steroidal constituent, physalolactone C.

|

|