| Cape Gooseberry - Physalis peruviana | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 1  Physalis peruviana  Fig. 2  P. peruviana, fruits of cape gooseberry  Fig. 3  P. peruviana Mannavan Shola, Anamudi Shola National Park  Fig. 4  P. peruviana, Kangaroo Valley to Berry road, NSW  Fig. 8  Flower, Auwahi, Maui, Hawai'i  Fig. 9 Flower, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i  Fig. 10  Cape Gooseberry, P. peruviana  Fig. 14  Fruit capsule, Auwahi, Maui, Hawai'i  Fig. 15 P.peruviana (Poha, Cape gooseberry), Fruit capsule, Auwahi, Maui, Hawai'i  Fig. 16  Die Früchte der Physalis,Kapstachelbeere, Andenbeere, Andenkirsche, lat. P. peruviana  Fig. 17  Cape Gooseberry P. peruviana, Coronel, Bío Bío, Chile  Fig. 18 P. peruviana  Fig. 23  Habit, Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i  Fig. 24 Harvesting poha at the 12-Trees Project orchard, Hawai'i  Fig. 25  Cape Gooseberry P. peruviana, Mount Albert, Auckland, New Zealand  Fig. 26 Fruit on display, Maui County Fair Kahului, Maui, Hawai'i  Fig. 27 Easy cape gooseberry preserve  Fig. 33 Cape goodeberry, Uchuva |

Scientific

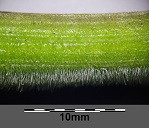

name Physalis peruviana L. Common names English: Cape-gooseberry, goldenberry, gooseberry-tomato, Peruvian ground-cherry, Peruvian-cherry; French: capuli, coqueret du Peru; German: Andenkirsche, Kapstachelbeere, peruanische Judenkirsche; Portuguese: groselha-do-Peru, bate-testa, camapú, erva-noiva-do-peru, physalis; Spanish: alquequenje, capulí; Spanish (Colombia): uchuva; Spanish (Ecuador): uvilla; Spanish (Peru); aguaymanto; Swedish: kapkrusbär 3 Synonyms Alkekengi pubescens Moench, Boberella peruviana (L.) E.H.L.Krause, P. chenopodifolia Lam., P. esculenta Salisb, P. latifolia Lam., P. peruviana var. latifolia (Lam.), P. puberula Fernald, P. tomentosa Medik. 2 Relatives Clammy Ground Cherry (P. heterophylla), Tomatillo (P. ixocarpa), Purple Ground Cherry (P. philadelphica), Strawberry Tomato (P. pruinosa), Ground Cherry, Husk Tomato (P. pubescens), Sticky Ground Cherry (P. viscosa). There is considerable confusion in the literature concerning the various species. Hybrids between them are also known. 6 Family Solanaceae (nightshade family) Origin Native to mountainous regions of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile 13 USDA hardiness zones 10-12 15 Uses Fruit Height Usually reaches 2-3 ft (1.6-0.9 m); may attain 6 ft (1.8 m) 4 Spread 6-8 ft 12 Plant habit Densely hairy herb; weak-stemmed shrub; sprawling habit similar in size/growth pattern to their relative, the tomato 1,10 Longevity Annual in temperate regions and a perennial in the tropics 4 Trunk/bark/branches Multi stemed; erect; ribbed, often purplish, spreading branches 1,4 Pruning requirement Should be severely pruned (ratooned) once a year after the harvest season 9 Leaves Nearly opposite; velvety; heart-shaped; pointed; randomly-toothed; 2 3/8-6 in. (6-15 cm) long; 1 1/2-4 in. (4-10 cm) wide 4 Flowers Hermaphrodite; bell-shaped; 0.4-0.8 in. (1-2 cm) long, 0.6-0.8 (15-20 mm) across; yellow; purple-brown spots in the throat 4 Fruit Berry is globose: 1/2 to 3/4 in. (1.25-2 cm) wide; smooth, glossy, orange-yellow skin; juicy pulp sweet; pleasing grape-like tang; husk is bitter, inedible; fruit not filling the calyx 4,13 Season Flowers year-round in frost-free areas 1 USDA Nutrient Content pdf Light requirement Full sun Soil tolerances Does best on sandy to gravelly loam 4 PH preference 5.0-6.5 9 Cold tolerance In South Africa, plants have been killed to the ground and failed to recover after a temperature drop to 30.5 ºF (-0.75 ºC) 4 Plant spacing 4-6 ft (1.2-1.8 m) apart in rows 8 Roots Absence of a taproot; shallow adventitious root system 14 Invasive potential * None reported Disease/pest resistance Bothered by several diseases and a host of insect pests 6 Known hazard Unripe fruits are poisonous. The plant is believed to have caused illness and death in cattle in Australia. 4 Reading Material Cape Gooseberry, Fruits of Warm Climates Cape Gooseberry, Physalis peruviana L., California Rare Fruit Growers Poha (Cape Gooseberry), Twelve Fruits Project, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa Poha, University of Hawai'i at Manoa pdf Origin The fruit is neither a gooseberry nor from the Cape of Good Hope. Plants were grown by settlers in the Cape in 1807, then carried to Australia and New Zealand in the 19th century and given that name. 14 Reportedly native to Peru and Chile, where the fruits are casually eaten and occasionally sold in markets but the plant is still not an important crop, it has been widely introduced into cultivation in other tropical, subtropical and even temperate areas. It is said to succeed wherever tomatoes can be grown. 4 It is surprising that this useful little fruit has received so little attention in the United States in view of its having been reported on with enthusiasm by the late Dr. David Fairchild in his well-loved book, The World Was My Garden. He there tells of its fruiting "enormously" in the garden of his home, "In The Woods", in Maryland, and of the cook's putting up over a hundred jars of what he called "Inca Conserve" which "met with universal favor." It is also remarkable that it is so little known in the Caribbean islands, though naturalized plants were growing profusely along roadsides in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica before 1913. 4 Sorting Physalis names, Multilingual Multiscript Plant Name Database ext link Description The genus Physalis, of the family Solanaceae, includes annual and perennial herbs bearing globular fruits, each enclosed in a bladderlike husk which becomes papery on maturity. 4 The cape gooseberries is a soft-wooded, perennial, somewhat vining plant usually reaching 2 to 3 ft. in height. Under good conditions it can reach 6 ft. but will need support. The purplish, spreading branches are ribbed and covered with fine hairs. 6 Leaves/Stems

Fig. 5. Hairy bottom side of leaf Fig. 6. P. peruviana, Jardín Botánico José Celestino Mutis, Colombia Fig. 7. P. peruviana, hairy stem Flowers The first yellow, bell-shaped flowers appear 4 to 5 weeks after transplanting during the onset of warm spring days in April and continue flowering through November unless damaged by an early frost. 7 In the leaf axils, bell-shaped, nodding flowers to 3/4 in (2 cm) wide, yellow with 5 dark purple-brown spots in the throat, and cupped by a purplish-green, hairy, 5-pointed calyx. After the flower falls, the calyx expands, ultimately forming a straw-colored husk much larger than the fruit it encloses (Fig. 18,20). 4

Fig. 11. P. peruviana, flower bud Fig. 13. Flower bud, sliced open Pollination Flowering of P. peruviana occurs year round in frost-free warmer areas starting 70-80 days after sowing, while the time between flower primordia initiation and anthesis is about 3 weeks. Flowers are readily pollinated by insects and winds. Stigmas are receptive two days before release of pollen, favouring cross-pollination - estimated at 54% (Lagos et al., 2008). The fruit take 85-100 days to develop from anthesis. 5 Cape gooseberries are self-pollinated but pollination is enhanced by a gentle shaking of the flowering stems or giving the plants a light spraying with water. 6 Fruit The fruit is a berry with smooth, waxy, orange-yellow skin and juicy pulp containing numerous very small yellowish seeds. As the fruits ripen, they begin to drop to the ground, but will continue to mature and change from green to the golden-yellow of the mature fruit. The unripe fruit is said to be poisonous to some people. 6 Yields of 150 to 300 fruits per plant are not unusual.The fruit is quite durable when left in the husk. Goldenberries are generally sold with the husk left on as many chefs use the husk for decorative purposes. After harvest, the ripe fruit may last several months without refrigeration, if kept dry. They also may be picked partially green and allowed to ripen, but these fruit never become as sweet as vine-ripened fruit. 7

Fig. 19. P. peruviana, berry surrounded by the inflated calyx Fig. 20. Berry surrounded by the inflated calyx, on the right calyx partly removed Fig. 21. Berry, cut open Fig. 22. Seeds Harvesting In rainy or dewy weather, the fruit is not picked until the plants are dry. Berries that are already wet need to be lightly dried in the sun. The fruits are usually picked from the plants by hand every 2 to 3 weeks, although some growers prefer to shake the plants and gather the fallen fruits from the ground in order to obtain those of more uniform maturity. 4 Harvest starts 4–7 months after transplanting. Fruit maturity is judged on the change in the fruit skin color from green to yellow or orange. The ideal is to harvest between the green-yellow stage and the dark yellow or orange stage. Changes in the color of the calyx are not indicative of fruit maturity. 14 Postharvest quality Poha will last up to several months dry and in-husk. Large commercial producers store them in-husk at 33°F. They will keep more than a year when husked and frozen. The husks are kept on when shipping the fruit, and it should be stored dry. 8 Culture Very good crops are obtained on rather poor sandy ground. The plant needs full sun but protection from strong winds; plenty of rain throughout its growing season, very little when the fruits are maturing. 4 It does not like heavy nor excessively wet soils. On highly fertile alluvial soil, the plant becomes very vegetative and the fruit fail to color properly. 14 They flower and fruit best in fairly cool weather; high temperatures are detrimental to flowering and fruiting. Hence, in areas with a seasonal climate (also in the subtropics) the crop is timed to fruit in the cool season. 17 After fruit ripening leaves turn yellow and fall. Most of the fibrous root system is found between 4-6 in. (10-15 cm) depth while some main roots can go down to 20-36 in. (50-80 cm). 14 Propagation Dried ripe fruits from selected clones of the previous seasons are fermented in water for up to 5 days. After the seeds are separated from the pulp, they are planted in flats of sterile peat-lite mix. The flats are kept continually moist. Seeds germinate in 8 to 14 days in an unheated greenhouse. The seedlings are field planted when they are 6-8 in. (15-20 cm) tall with at least 3 ft (1 m) between each plant. 7 There are 5,000 to 8,000 seeds to the ounce (28 g) and, since germination rate is low, this amount is needed to raise enough plants for an acre, 2 1/2 oz (70 g) for a hectare. Sometimes propagation is done by means of 1-year-old stem cuttings treated with hormones to promote rooting, and 37.7% success has been achieved. The plants thus grown flower early and yield well but are less vigorous than seedlings. Air-layering is also successful but not often practiced. 4 Germination starts after 10–15 days. Flowering occurs 65–75 days after planting. 14 With very small seeds such as Cape Gooseberry, watering overly dry soil can cause the seeds to dislodge from their position and sink deep into cracks in the soil. Seeds that sink deeply into soil will not be able to reach the soil surface once germinated. 11 Pruning Very little pruning is needed unless the plant is being trained to a trellis. Pinching back of the growing shoots will induce more compact and shorter plants. 6 Fertilizing The cape gooseberry seems to thrive on neglect. Even moderate fertilizer tends to encourage excessive vegetative growth and to depress flowering. High yields are attained with little or no fertilizer. 6 Irrigation The plant needs consistent watering to set a good fruit crop, but can't take "wet feet". Where drainage is a problem, the plantings should be on a gentle slope or the rows should be mounded. Irrigation can be cut back when the fruits are maturing. The plants become dormant during drought. 6 Diseases/pests Cape gooseberries are bothered by several diseases, including Alternaria spp. and powdery mildew. The plants are also prone to root rots and viruses when grown on poorly drained soil. A host of insect pests also attack the plants, namely cut worm, stem borer (Heliotis suflixa), leaf borer (Epiatrix spp.), fruit moth (Phthorimaea), Colorado potato beetle, flea beetle and striped cucumber beetle (Acalymma vittata). Greenhouse grown plants are attacked by white fly and aphids. The stored fruit can be adversely affected by Penicillium and Botrytis molds. 6 Food Uses In addition to being canned whole and preserved as jam, the cape gooseberry is made into sauce, used in pies, puddings, chutneys and ice cream, and eaten fresh in fruit salads and fruit cocktails. In Colombia, the fruits are stewed with honey and eaten as dessert. The British use the husk as a handle for dipping the fruit in icing. 4 The canned fruits have been exported from South Africa and the jam from England. 4 Cape gooseberries cooked with apples or ginger make a very distinctive dessert. The fruits are also an attractive sweet when dipped in chocolate or other glazes or pricked and rolled in sugar. The high pectin content makes cape gooseberry a good preserve and jam product that can be used as a dessert topping. The fruit also dries into tasty "raisins". 6 In tropical America, the fruit halves are used in avocado salads. Cape gooseberries are commonly canned in syrup. 13

Fig. 28. A lychee mojito, and a cape gooseberry and ginger concoction Fig. 31. Cape gooseberries and strawberry Flaugnarde The berry contains 0.8% citric acid. It is rich in vitamins A and P and contains about 30 mg vitamin C and 2.8 mg B12 per 100 g edible portion, and much pectin. 17 Medicinal Properties ** In Colombia, the leaf decoction is taken as a diuretic and antiasthmatic. In South Africa, the heated leaves are applied as poultices on inflammations and the Zulus administer the leaf infusion as an enema to relieve abdominal ailments in children. 4 Indian chemists have isolated from the leaves a minor steroidal constituent, physalolactone C. 4 Other Edible Physallis species: Coastal Groundcherry, P. angustifolia, University of Florida pdf Cutleaf Groundcherry, P. angulata Ground Cherry, Wild Husk Tomatoes, Almost, Eat The Weeds Tomatillo, P. philadelphica Tomato, Husk, P. pruinosa, University of Florida pdf (archived) General The fruits are strung for leis and have been popular with Big Island cowboys because they are long lasting when worn as hat leis. 12 Physalis peruviana was given a botanical species description by Carl Linnaeus in 1763 and given the genus name Physalis after the Greek: φυσαλλίς - physallís, “bladder, wind instrument” in reference to the calyx that surrounds the berry. The specific name peruviana refer to the country of Peru, one of the countries of the berry's origin. 16

Fig. 32. Cape gooseberry distribution map, wild populations Further Reading Goldenberry, Passionfruit, & White Sapote: Potential Fruits for Cool Subtropical Areas, New Crops, Purdue University Physalis peruviana, PROSEA Foundation Older Material Equipment for Husking Poha Berries, University of Hawai'i pdf List of Growers and Vendors |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bibliography 1 "Physalis peruviana." Data sheet, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Ecocrop FAO, ecocrop.fao.org/ecocrop/srv/en/dataSheet?id=1686. Accessed 1 Sept. 2019. 2 "Physalis peruviana L. synonyms." The Plant List (2013), Version 1.1, www.theplantlist.org/tpl/record/kew-2549655. Accessed 2 Sept. 2019. 3 "Taxon: Physalis peruviana L." USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System, Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN-Taxonomy), National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland, 2019, U.S. National Plant Germplasm System, npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?id=102390. Accessed 2 Sept. 2019. 4 Fruits of Warm Climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, 1987. 5 Lagos B., T. C., et al. "Sexual reproduction of the cape gooseberry." Acta Agronómica, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Invasive Species Compendium, 20093289811, 2008, CABI, www.cabi.org/isc/abstract/20093289811. Accessed 10 Sept. 2019. 6 "Cape Gooseberry, Physalis peruviana L." California Rare Fruit Growers, crfg.org.pubs/ff/cape-gooseberry.html. Accessed 10 Sept. 2019. 7 New Crops. Edited by Jules Janick and J. E. Simon, Wiley, New york, 1993. 8 Love, Ken, et al. "Twelve Fruits With Potential Value-Added and Culinary Uses." University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, CTAHR, 2007. Accessed 10 Sept. 2019. 9 Chia, C. L., et al. "Poha." Dept. of Horticulture and CTAHR Cooperative Extension Service, Fact Sheet Horticultural Commodity no. 3, Jan. 1997, CTAHR, www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/HC-3.pdf. Accessed 11 Sept. 2019. 10 McCain, Richard. "Goldenberry, Passionfruit, & White Sapote: Potential Fruits for Cool Subtropical Areas." New Crops, Edited by J. Janick and J. E. Simon, pp. 479-486 1993, NewCROP ™, hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/proceedings1993/V2-479.html#GOLDENBERRY. Accessed 11 Sept. 2019. 11 "Cape Gooseberry, Physalis peruviana, a.k.a. Ground Cherry, Golden Berry." Trade Winds Fruit, www.tradewindsfruit.com/content/cape-gooseberry.htm. Accessed 11 Sept. 2019. 12 Staples, George W. and Derral R. Herbst. A Tropical Garden Flora, Plants Cultivated in the Hawai'ian Islands and Other Tropical Places. Honolulu, Bishhop Museum Press, 2005. 13 Blancke, Rolf. Tropical Fruits and Other Edible Plants of the World: An Illustrated Guide. China, Comstock Publishing Associates, a division of Cornell University Press, 2016. 14 Duarte, Odilo, and Robert E. Paull. Exotic Fruits and Nuts of the New World. Cambridge, CABI, 2015. 15 "Physalis peruviana." Plants For A Future, pfaf.org/User/plant.aspx?LatinName=Physalis+peruviana. Accessed 11 Sept. 2024. 16 "Physalis peruviana." Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana. Accessed 11 Sept. 2019. 17 Verhoeven, G. "Physalis peruviana." Edible fruits and nuts, Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2, Edited by E. W. M. Verheij, and R. E. Coronel, PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia, record 1533, 1991, PROSEA, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), www.prosea.prota4u.org/view.aspx?id=1533. Accessed 11 Sept. 2024. Photographs Fig. 1 3268zauber. "Physalis peruviana." Wikimedia Commons, 4 Jan. 2009, GFDL, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Physalis_Nahaufnahme.JPG. Accessed 11 Sept. 2024. Fig. 2 Leidus, Ivar. "Physalis peruviana, Fruits of cape gooseberry." Wikimedia Commons, 24 Nov. 2020, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Physalis_peruviana_fruits_close-up.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2024. Fig. 3 Vinayaraj. "Physalis peruviana, Mannavan Shola, Anamudi Shola National Park, Kerala during Munnar Butterfly Survey." Wikimedia Commons, 25 Sept. 2015, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Physalis_peruviana,_Cape_Gooseberry_at_Mannavan_Shola,_Anamudi_Shola_National_Park,_Kerala_(6).jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2024. Fig. 4 Fagg, M. "Physalis peruviana, Kangaroo Valley to Berry road, NSW." Australian Plant Image Index, Australian National Botanic Gardens, Australian Government, Canberra, dig.8046, 3 May 2009, IBIS database, www.anbg.gov.au/photo/index.html. Accessed 8 Sept. 2019. Fig. 5 lefnaer, Stefan. "Physalis peruviana, Hairy bottom side of leaf." Wikimedia Commons, 10 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_sl20.jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 6 Weigell, Philipp."Physalis peruviana, Jardín Botánico José Celestino Mutis, Colombia." Wikimedia Commons, 5 July 2008, (CC BY 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_(3).jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 7 lefnaer, Stefan. "Physalis peruviana, Hairy stem." Wikimedia Commons, 10 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_sl19.jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 8 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis peruviana (Poha, Cape gooseberry), Flower, Auwahi, Maui, Hawai'i." Starr Environmental, no. 040131-0076, 1 Jan. 2004, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24604149321. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 9 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis peruviana (Poha, Cape gooseberry), Flower, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawaii." Starr Environmental, no. 170224-0952, 24 Feb. 2017, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=33340752356. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 10 "Physalis peruviana." Acta Plantarum, Galleria della Flora, (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), www.actaplantarum.org/galleria_flora/galleria1.php?view=1&id=3801. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023. Fig. 11 juan_carlos_caicedo_hernandez. "Physalis peruviana L." iNaturalist Research Grade, Global Biodiodiversity Information Facility, no. 28910043, 15 July 2019, GBIF, (CC BY-NC 4.0), www.gbif.org/occurrence/2294521431. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019. Fig. 12 lefnaer, Stefan. "Physalis peruviana, Flower bud." Wikimedia Commons, 10 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_sl21.jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 13 lefnaer, Stefan. "Physalis peruviana, Flower bud, opened." Wikimedia Commons, 10 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_sl22.jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 14 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis peruviana (Poha, Cape gooseberry), Fruit capsule, Auwahi, Maui, Hawai'i." Starr Environmental, no. 030628-0029, 28 June 2003, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24007707434. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 15 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis peruviana (Poha, Cape gooseberry), Fruit capsule, Auwahi, Maui, Hawai'i." Starr Environmental, no. 030628-0026, 28 June 2003, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24635837565. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 16 Plenuska. "Die Früchte der Physalis, Kapstachelbeere, Andenbeere, Andenkirsche, lat. Physalis peruviana." Wikimedia Commons, 30 Aug. 2015, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Die_Physalis.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2024. Fig. 17 cfaundeze."Cape gooseberry, Physalis peruviana, Coronel, Bío Bío, Chile." iNaturalist Research Grade, 4 Mar. 2024, (CC BY-SA 4.0), www.inaturalist.org/observations/213546167. Accessed 12 Sept. 2024. Fig. 18 Wrightson, Barney. "Orange cape gooseberry." Flickr, 21 July 2007, (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), Image cropped, www.flickr.com/photos/barney_wrightson/869870888/. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023. Fig. 19 lefnaer, Stefan. "Physalis peruviana, Berry surrounded by the inflated calyx." Wikimedia Commons, 11 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_sl23.jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 20 lefnaer, Stefan. "Physalis peruviana, Berry surrounded by the inflated calyx, on the right calyx partly removed." Wikimedia Commons, 11 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_sl24.jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 21 lefnaer, Stefan. "Physalis peruviana, Berry, cut open." Wikimedia Commons, 11 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_sl25.jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 22 lefnaer, Stefan. "Physalis peruviana, Seeds." Wikimedia Commons, 11 Nov. 2018, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Physalis_peruviana#/media/File:Physalis_peruviana_sl26.jpg. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 23 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis peruviana (Poha, Cape gooseberry), Habit, Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i." Starr Environmental, no. 061225-2953, 25 Dec. 2008, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24753374522. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 24 Love, Ken. "Harvesting poha at the 12-Trees Project orchard." Twelve Fruits With Potential Value-Added and Culinary Uses, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, 2007, HawaiiFruit.net, www.hawaiifruit.net/12trees.html. Accessed 10 Sept. 2019. Fig. 25 Doogan, Brendan."Cape gooseberry, Physalis peruviana, Mount Albert, Auckland, New Zealand." iNaturalist Research Grade, 12 Sept. 2023, (CC BY-SA 4.0), www.inaturalist.org/observations/183040380. Accessed 12 Sept. 2024. Fig. 26 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis peruviana (Poha, Cape gooseberry), Fruit on display, Maui County Fair Kahului, Maui, Hawai'i" Starr Environmental, no. 120930-0304, 30 Sept. 2012, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=25166048196. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 27 Aparna. "Easy Cape Gooseberry Preserve." My Diverse Kitchen, 10 Mar. 2029, (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), www.mydiversekitchen.com/easy-cape-gooseberry-preserve. Accessed 8 Mar. 2023. Fig. 28 Hartnup, Ruth. "A lychee mojito, and a cape gooseberry and ginger concoction." Colourful cocktails, 13 Sept. 2008, Flickr, (CC BY 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/ruthanddave/2879198548/. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 29,30 Hans. "Physalis peruviana." Pixabay, pixabay.com/photos/dessert-food-gourmet-nutrition-1522080/. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 31 Raymond. "Cape Gooseberries and Strawberry Flaugnarde." Ang Sarap, Published 30 Apr. 2013, Updated 1 May 2020, (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0), www.angsarap.net/2013/04/30/cape-gooseberries-and-strawberry-flaugnarde/. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023. Fig. 32 Wunderlin, R. P., et al. "Physalis peruviana, Species Distribution Map." Atlas of Florida Plants, [S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute.] Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, 2019, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=307&syn_name=Physalis+peruviana. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 33 User JuanseG~commonswiki. "Cape gooseberry, Uchuva." Wikmedia Commons, Public domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Uchuva_2005.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2024. * UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas ** The information provided above is not intended to be used as a guide for treatment of medical conditions using plants. Published 21 Sept. 2019 LR. Last update 12 Sept. 2024 LR |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||