From Neglected crops: 1492 from a different perspective

by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Tomatillo, husk-tomato

(Physalis philadelphica)

Common

Names: Physalis philadelphica Lam.

Family: Solanaceae

Common

Names: English:

tomatillo, husktomato, jamberry, ground cherry; Spanish: tomate de

cáscara, tomate de fresadilla, tomate milpero, tomate verde, tomatillo

(Mexico), miltomate (Mexico, Guatemala)

The tomatillo or husk-tomato (Physalis philadelphica)

is a solanaceous plant cultivated in Mexico and Guatemala and

originating from Mesoamerica. Various archaeological findings show that

its use in the diet of the Mexican population dates back to

pre-Columbian times. Indeed, vestiges of Physalis

sp. used as food have been found in excavations in the valley of

Tehuacán (900 BC-AD 1540). In pre-Hispanic times in Mexico, it was

preferred far more than the tomato (Lycopersicon

sp.). However, this preference has not been maintained, except in the

rural environment where, in addition to the persistence of old eating

habits, the tomato's greater resistance to rot is still valued.

Possibly because of the fruit's colourful appearance and because there

are ways of eating it which are independent of the chili (Capsicum sp.), the tomato achieved greater acceptance outside Mesoarnerica and Physalis

sp. was marginalized, or its cultivation was discontinued, as happened

in Spain. It is relevant to note that only in central Mexico is the

fruit of Lycopersicon sp. known chiefly as "jitotomate", since in other parts of the country and in Central and South America it is called "tomate".

P. philadelphica

was domesticated in Mexico from where it was taken to Europe and other

parts of the world; its introduction into Spain has been well

documented. Indeed, it is believed that this species originated in

central Mexico where, at present, both wild and domesticated

populations may be found.

The name "tomato" derives from the Nahuatl

"tomatl"; this word is a generic one for globose fruits or berries

which have many seeds, watery flesh and which are sometimes enclosed in

a membrane.

Of the great number of species of the genus Physalis, very few are used for their fruit. P. peruviana L. has been grown in Peru since pre-Columbian times. The fruit of P. chenopodifolia is picked in the state of Tlaxcala, Mexico. In Europe, P. alkekengi

is grown as an ornamental plant because of the colourful calyx of its

fruit, and its fruit also is used in central and southern Europe. The

tomatillo has been a constant component of the Mexican and Guatemalan

diet up to the present day, chiefly in the form of sauces prepared with

its fruit and ground chilies to improve the flavour of meals and

stimulate the appetite.

The tomatillo is also used in sauces with green chili, mainly to lessen

its hot flavour. The fruit of the tomatillo is used cooked, or even

raw, to prepare purees or minced meat dishes which are used as a base

for chili sauces known generically as salsa verde (green sauce); they

can be used to accompany prepared dishes or else be used as ingredients

in various stews. An infusion of the husks (calyces) is added to tamale

dough to improve its spongy- consistency, as well as to that of

fritters; it is also used to impart flavour to white rice and to

tenderize red meats.

About ten years ago the crop began to be

industrialized in Mexico and agro-industries are currently estimated to

process 600 tonnes per year, 80 percent of which is exported to the

United States as whole tomatillos, without a calyx and canned, while

the remainder is used in the preparation of packaged sauces for the

domestic market.

P. philadelphica

is acquiring importance as an introduced crop in California as a result

of the growing popularity of Mexican food in the United States.

Furthermore, numerous medicinal properties are attributed to it.

Official statistics show that, in 1984, 15 248 ha were sown in Mexico,

with a total production value of 5 797 million pesos and an average per

capita consumption of 2.32 kg. Both in Mexico and Guatemala, wild

tomato fruit from cultivated fields has a predominant place in the

diet, hence in some regions it is an important product among those

gathered in rural areas for immediate consumption and for sale.

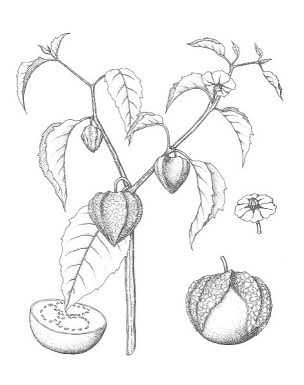

Botanical description

P. philadelphica is an

annual of 15 to 60 cm; it is subglabrous, sometimes with sparse hairs

on the stem. The leaf lamina is 9 to 13 x 6 to 10 mm; its apices are

acute to slightly acuminate, with irregularly dentate margins and two

to six teeth on each side of the main tooth, of 3 to 8 mm. The pedicels

are 5 to 10 mm, the calyx has ovate and hirsute lobules measuring 7-13

mm. The corolla is 8 to 32 mm in diameter, yellow and sometimes has

faint greenish blue or purple spots. The anthers are blue or greenish

blue. The calyx is accrescent, reaching 18 to 53 x 11 to 60 mm in the

fruit, and has ten ribs. The fruit is 12 to 60 x 10 to 48 mm in size

and sometimes tears the calyx.

Figure 11. Tomatillo, husk-tomato (Physalis philadelphica): details of the flower and fruit with an accrescent calyx, and a cross-section of the fruit

Ecology and phytogeography

The P. philadelphica plant grows from southern Baja California to Guatemala, from 10 m in Tres Valles, Veracruz, to 2 600 m in the valley of Mexico.

Genetic diversity

There are many local or indigenous varieties of P. philadelphica

which producers recognize by fruit colour and size as well as by the

plant's growth habit although, within these varieties, there is wide

variation, possibly because of their self-incompatibility. The

wild forms are very often found growing in cultivated fields in

traditional agricultural systems, mainly in combination with maize,

beans and gourd. In Mexico, another type of tomato is found which is

sold on the markets as wild from cultivated fields. In actual fact, it

is a cultivated tomato with a small fruit; the reason for this

fraudulence lies in the fact that the price of wild tomatoes growing in

cultivated fields is double that of the cultivated tomatoes.

The

diameter of the 'fruit is bigger in the Mexican tomato (1.08 to 4.9 cm)

than in the Guatemalan tomato (1.04 to 2.89 cm). However, these

measurements correspond mainly to the cultivated tomatoes. In

Guatemala, purplish green, yellowish green and purple tomatoes are

preferred; in Mexico, on the other hand, the variation in colour is

greater, as there are yellow, various shades of green and purple fruits.

The

characteristics showing the greatest variation are fruit size, colour

and average weight; the number and weight of fruit per plant; the

consistency and colour of the flesh; the colour and length of the

calyx; flower size; the number and size of the nodes on the first

bifurcation of the plant; stem colour; the size and number of teeth per

leaf; branching; earliness and pubescence.

The tomatillo or husk-tomato

is a vegetable which is used widely and continuously throughout the

year its current situation is as follows:

· wild fruit found growing in

cultivated fields is picked and sold;

· small-fruited varieties, similar

to those found growing wild in cultivated fields, are specifically

grown for the market;

· there are numerous local indigenous selections

with a large fruit;

· the Mexican varieties Rendidora and Rendidora

mejorada, produced by INIFAP's plant improvers, are rarely used.

In

several regions of Mexico the species P. chenopoclifolia Lam. grows wild in cultivated fields: its use as a potential resource has been recorded.

The species of Physalis

in Mexico and Guatemala are not in any immediate danger of genetic

erosion. However, extensive explorations must be carried out to collect

both cultivated material and wild plants found in cultivated fields so

as to consolidate the gene banks and contribute material and

information towards the genetic improvement programme for this crop. At

present, INIFAP's gene bank in Mexico has approximately 190 collections

of Physalis species, obtained

from four of the country's states while, in the gene bank at the

University of San Carlos, there are 41 accessions from several regions

of Guatemala.

Cultivation practices

Cultivation

practices are cotnmon to the majority of the solanaceous plants.

Transplanting of the tomato is widespread, principally in the areas

where frosts make it essential. Its advantages include saving on seed,

reduced weeding and the possibility of starting the cycle while there

is still another crop on the ground as well as shortening the growing

cycle. Generally speaking, weeding is done by hand or using mechanical

implements. Most growers use chemical fertilizers (nitrogen and

phosphorus): the doses range from 120 to 240 kg of nitrogen and from 60

to 150 kg of phosphorus per hectare. Given the resources, growers are

confident they can control pests and diseases affecting the crop.

However, they would need to know more about the doses, appropriateness,

products and cost-effectiveness ratios of these control practices.

The

tomatillo or husk-tomato is grown mainly on irrigated land. Because of

this, sowing dates vary within each producing area, which explains why

this tomato is found on the market throughout the year. In some areas

it is grown on dry land, both using residual humidity and during the

heavy rainstorms. Sowing density ranges from 17 000 to 25 000 plants

per hectare. The fruit is harvested when it reaches its normal size,

when it has a firm consistency and generally when the apex of the calyx

has begun to break. Small-fruited varieties, selected for this purpose,

undergo cultivation practices similar to those used for the large

tomato.

The greater percentage of dormancy occurs in the seed

recently extracted from the fruit. In less than a year it reaches its

maximum germination potential, losing it drastically as from the third

year under commercial storage conditions. For marketing purposes, the

small fruit must not fill the calycinal envelope. On the other hand,

the large tomato must fill it completely and should preferably break it

to reveal part of the fruit (this is visually attractive to the

purchaser). The wild tomatillo found in cultivated fields adapts to

various environments but it appears mainly on cultivated ground and

sometimes care is taken to prevent its removal during weeding and

earthing up. It appears most commonly on parts of land where vegetable

waste is concentrated and burned after clearance. This tendency may be

due to enrichment of the soil with the ash, the effect of which is to

stimulate high temperatures in the seeds. Its apparent resistance to

the herbicide 2,4-D amine, which is widely used on maize, may help its

survival and even its spread (through the reduction of competifion in

the treated fields) in some agricultural regions.

The only two

Mexican improved varieties, Rendidora and Rendidora mejorada, have the

following characteristics: a smaller and more uniform habit; few or no

hollow fruits; and firmer fruit of a lime-green colour.

Prospects for improvement

The

variety Rendidora was formed from the best collections selected in the

state of Morelos, where improvement work was carried out. Rendidora

mejorada was derived from this variety. In Guatemala, in spite of the

wide genetic variation recognized, genetic improvement of this crop is

still in its early stages. The characteristics most affected by the

environment are leaf size and shape, growth habit and the growing cycle

of the plant. Soil fertility stands out as an environmental factor in

expression of the phenotype.

Genetic improvement work in Mexico

should aim at: plants with large and firm, deep green (not yellow)

fruit; high yield, wide adaptation and resistance to viral diseases and

powdery mildew (Oidium spp.).

Improvement aims in Guatemala should be the same, except regarding

fruit colour, since purplish green and yellowish green tomatoes are

preferred in that country.

P. chenopodifolia

is in the initial stage of domestication and shows a favourable

response to agricultural practices; accordingly, it must be collected

and evaluated so that the potential for better utilization in the

future may be established.

Bibliography

Azurdia,

P.C.A. & González, S.M. 1986. Informe .final del proyecto de

recolección de algunos cultivos nativos de Guatemala. Guatemala,

University of San Carlos/ICTA/ IBPGR.

Azurdia, P.C.A., Carrillo, F.,

Rodríguez, B., Vázquez, F. & Martínez, V. 1990. Caracterización y

evaluación preliminar de algunos cultivos nativos de Guatemala.

Guatemala, University of San Carlos/ICTA/IBPGR.

Bukasov, S.M. 1963. Las plantas cultivadas de México, Guatemala y Colombia. Lima, IICA, Misc. Publ. No. 20.

Callen,

E.O. 1966. Analysis of the Tehuacan coprolites. In D.S. Byers, ed. The

prehistory of the Tehuacan Valley. I. Environment and subsistence, p.

261-289. Austin, USA, University of Texas Press.

Cruces, C.R. 1987. Lo que México aportó mundo. Mexico City, Panorama.

Del Monte, D. de G.J.P. 1988. Presencia, distribución y origen de Physalis philadelphica Lam. en la zona centro de la Península Ibérica. Candollea, 43(1): 93-100.

De Sahagfin, B. 1956. Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva Espafia, Mexico City, Porraa.

Dressler,

R.L. 1953. The pre-Columbian cultivated plants of Mexico. Bot. Mus,

Leqfl. Harv. Univ., 16(6): 115-172. Fernández, B.L., Yani, M. &

Zafiro, M. 1987. ...Y la comida se hizo. 4 para celebrar. Mexico City,

ISSSTE.

García, S.F. 1985. Physalis

L. In Flora fanerogqmica del valle de México. J. Rzedow ski

& G.C. de Rzedowski, eds. Mexico City, Instituto de Ecología.

Harlan, J.R. 1975. Crops and man. Madison, Wis., USA, ASA.

Hernández, F. 1946. Historia de las plantas de Nueva España. 1V1exico City, UNAM.

Hudson, W.D., Jr. 1983. The relationships of wild and domesticated tomato. Physalis philadelphica Lamarck (Solanaceae). Bloomington, USA, Indiana University. (thesis)

Hudson, W.D., Jr. 1986. Relationships of domesticated and wild Physalis philadelphica. in W.G. D' Arcy, ed. Solanaceae: biology and systematics. New York, Columbia University Press.

Martínez,

M. 1954. Plantas (idles de la flora c/c México. Mexico, Botas.

Menzel, Y.M. 1951. The cytotaxonomy and genetics of Physalis. Proc. Am. P hil. Soc., 95(2): 132-183.

Mera, 0.L.1V1. 1987. Estudio comparativo del proceso de cultivo de la arvense Physalis chenopodifolia Lamarck y Phvsalis philadelphica var. philadelphica cultivar Rendidora'. Chapingo, Mexico, Colegio de Postgraduados. (thesis)

Montes,

H.S. 1989. Evaluación de los efectos de la domesticación sobre el

tomate Physalis philadelphica Lam. Chapingo, Mexico, Colegio de

Postgraduados. (thesis)

Pandey, K.K. 1957. Genetics of self-incompatibility in Physalis ixocarpa

Brot. A new system. Arn..I . Bot., 44: 879-887. Quirós, C.F. 1984.

Overview of the genetics and breeding, of husk-tomato. Hort. Sci.,

19(6): 872-874.

Saray, M.C.R., Palacios, A.A. & Villanueva, E.N.

1978. Rendidora' nueva variedad de tomate de cascara. Foll. Div. No 73.

Campo Agrícola Experimental Zacatepec. Mexico, CIAMECINIA-SARH.

Waterfall, U.T. 1967. Physalis

in Mexico, Central America and the West Indies. Rhoclora, 69: 8 2-120,

203-239, 319-329.

Williams, E.D. 1985. Tres arvenses solanaceas

comestibles y su proceso de domesticación en el estado de Tlaxcala,

México. Chapingo, Mexico, Colegio de Postgraduados. (thesis)

|

|