| Tomatillo - Physalis philadelphica | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 1 Tomatillo, Physalis philadelphica  Fig. 2 Large-flowered tomatillo P. philadelphica, Villaflores, Chis., México  Fig. 3  Tomatillo groundcherry (P. philadelphica) seedling  Fig. 4  Tomatillo plant with buds, pubescent stem and serrated leaves noticeable  Fig. 5  Habit, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i  Fig. 6  Tomatillo, P.ixocarpa,Tatarstan, Russia  Fig. 7  Flowers and leaves, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i  Fig. 8   Fig. 9  Solitary, nodding, axillary flower  Fig. 10  Flower variation  Fig. 14  Tomatillo P. philadelphica in a garden in Kluse (Emsland)  Fig. 15  Flower being pollinated  Fig. 16  After pollination, the petals fall and the fruit begins to grow  Fig. 17  Tomatillo, P. ixocarpa, Loulé, Portugal  Fig. 18   Fig. 19 Immature berry, calyx partially removed  Fig. 25  The fruit is enclosed in a husk (enlarged purple veined calyx), but unlike the cape gooseberry, the inflated calyx stops growing before the berry and is usually split by the expanding berry. 6  Fig. 26  Purple tomatillos  Fig. 27 Tomatillo, miltomate, tomate verde, tomate de fresadilla, P. ixocarpa, solanáceas  Fig. 28  Tomatillo groundcherry (P. philadelphica), healthy plant showing plant architecture and growth habit  Fig. 29  Tomatillos in grocery store, Cambridge. Massachusetts, USA.  Fig. 30 Tomatillos in a box at a grocery store  Fig. 31  Roasted corn and tomatillos salsa tacos |

Scientific

name Physalis philadelphica Lam (usually identified as P. ixocarpa in the older literature) 9 Common names English: husk-tomato, large-flower tomatillo, tomatillo ground-cherry; French: alkékenge du Mexique, coqueret, tomate fraise; German: mexikanische Blasenkirsche; Spanish: miltomate, tomate, tomate de cáscara, tomate verde, tomatillo; Swedish: tomatillo 1 Synonyms P. atriplicifolia Poir., P. cavaleriei H.Lév., P. geniculata (M.Martens & Galeotti) Miers, P. laevigata M.Martens & Galeotti, P. megistocarpa Zuccagni, P. megistocarpos Zuccagni, P. mexicana Molina ex Colla, P. ovata Poir., P. philadelphica var. minor Dunal, P. philadelphica f. pilosa Waterf., P. violacea Carrière, Saracha geniculata M.Martens & Galeotti 2 Relatives Clammy ground cherry (P. heterophylla), strawberry tomato (P. pruinosa), ground cherry, husk tomato (P. pubescens), sticky ground cherry (P. viscosa). There is considerable confusion in the literature concerning the various species. Hybrids between them are also known. 11 Family Solanaceae (nightshade family) Origin Mesoamerica; cultivated in Northern (Mexico) and Southern America (El Salvador, Guatemala) 5 USDA hardiness zones 8-10 16 Uses Edible fruit Height May grow 2-4 ft (0.5-1 m), but if left unstaked, will spread out radially for a few feet 2 Spread Often prostrate and spreading 7 Longevity Perennial vegetable; usually grown as an annual Trunk/bark/branches Stems branched; glabrescent or sparingly pubescent; single stem, multi stem 3,13 Leaves Ovate, pointed at apex; wedge-shaped at base; sometimes wavy-margined; 2½ in. (6.25 cm) long; 1¼ in. (3.2 cm) wide 7 Flowers Calyx campanulate, divided to halfway; corolla pale yellow, spotted in throat; anthers bluish to purplish, 0.08-0.12 in. (2-3 mm) 13 Fruit Green or yellow berries; sticky; up to 2.5 in. (6 cm); nearly covered by the calyx which forms a husk around the fruit 9 Season Aug.to Oct.; the growing period for tomatillo is short (3 to 4 months) and several overlapping crops could be produced USDA Nutrient Content Light requirement Full sun Soil tolerances Well-drained, sandy loam soils; soil suitable for tomatoes PH preference Optimal: 6-7; absolute: 5-8 3 Cold tolerance Optimal: 59-77 °F (15-25 °C); absolute: 46-88 °F (8-31 °C) 3 Plant spacing 16 in. (40 cm) between plants; 4 ft (1.25 m) between rows 7 Invasive potential * None reported Pest/disease Subject to pests and diseases common to the tomato Known hazard All parts of the plant, except the fruit, are poisonous Reading Material Tomatillo, Physalis ixocarpa Brot. ex Hornem, University of Florida pdf Tomatillo, husk-tomato, Neglected Crops Tomatillo: A Potential Vegetable Crop for Louisiana, Advances in New Crops, Purdue University Mexican Husk Tomato, Fruits of Warm Climates Taxonomy Note: Physalis ixocarpa has been sunk under P. philadelphica on the strength of advice received from Maggie Whitson of the Biology Dept. of Northern Kentucky University and the treatment in the African Plants Database. Its origins are no longer clear but is known as a naturalised species in Europe, Australia and Africa. 12 The taxonomic complexity of the genus is not yet clarified, especially between P. ixocarpa and P. philadelphica. 6 Origin The tomatillo or husk-tomato (Physalis philadelphica) is a solanaceous plant cultivated in Mexico and Guatemala and originating from Mesoamerica. Various archaeological findings show that its use in the diet of the Mexican population dates back to pre-Columbian times. 5 Tomatillo, which was introduced to the United States from Mexico, is popular with Latinos. For this reason it is grown to a very limited extent in south Florida for the Cuban Americans in that region. 10 Description Little known in the USA 50 years ago, the tomatillo, either fresh or bottled, is now widely found in supermarkets, and has also become grown in home gardens. Nearly all of the fresh tomatillo is imported from Mexico where the plant was domesticated before the arrival of the Spanish. 9 The tomatillo is a vegetable which is used widely and continuously throughout the year; its current situation is as follows: a) wild fruit found growing in cultivated fields is picked and sold; b) small-fruited varieties, similar to those found growing wild in cultivated fields, are specifically grown for the market; d) there are numerous local indigenous selections with a large fruit; e) the Mexican varieties Rendidora and Rendidora mejorada, produced by INIFAP's plant improvers, are rarely used. 5 Leaves Tomatillo seedlings form a single shoot which has three to five internodes above the cotyledons. The last internode ends with a flower, one leaf and two lateral ramifications. Each ramification has one node which terminates in the same pattern, one end flower, one leaf and two branches. This pattern continues until senescence with the exception that when two leaves are formed there is no further branching. 6 One characteristic of the main branches is that the internodes differ in length and have many adventitious roots. When these roots contact soil, they grow into the soil and are independent of the main root system. 6 Flowers The flowers are solitary in the axis of the leaves, sometime pendant in the axillary branches causing them to appear to be axillary between the two branches. The pendant blossoms are often hidden by the foliage and many of the flowers hang just above the ground. 6 The first flower bud is formed before the elongation of the primary shoot end, which is around the 3rd or 4th week after emergence, and flowering continues until senescence of the plant. 6

Fig. 11. Tomatillo P. philadelphica in a garden in Kluse (Emsland) Fig. 12. P. philadelphica (Tomatillo), flower, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i Fig. 13. Flower of tomatillo (P. ixocarpa) Fruit Tomatillo is similar to tomato plants, in that the biggest fruit are from the first flowers on the main branches. The lateral and sublateral branches produce more flower buds but they abscise and do not produce harvestable fruit. 6 The number of fruits set is variable, but generally fruit are set until the 10th and 11th weeks after emergence 6 Each plant will produce around 2 to 3 pounds of fruits and they will be ready for harvest about 60 to 75 days from transplanting. 18 The calix is inedible.

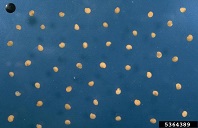

Fig. 20. Ripe tomatillo, partially opened Fig. 21. Tomatillo P. philadelphica in a garden in Kluse (Emsland) Fig. 22. Large-flowered tomatillo P. philadelphica, Country Club Rd, Borrego Springs, CA Varieties There are many local or indigenous varieties of P. philadelphica which producers recognize by fruit colour and size as well as by the plant's growth habit although, within these varieties, there is wide variation, possibly because of their self-incompatibility. 5 Tomatillo varieties can be categorized by fruit color. Green varieties include: Rendidora, (upright growth; high yields), Gigante, Tamayo, Toma Verde, and Gulliver Hybrid have more sprawling growth habits. Purple varieties include: Purple Coban, Purple De Milpa, and Purple Hybrid. 18 Harvesting Tomatillos are ripe when the fruit is firm and fills the papery husk. If green fruit turns yellow, it is overripe and less flavorful. The purple varieties are ripe when the green fruits turn purple and fill the husk. Fruit become soft when overripe. 18 The fruit is harvested when it reaches its normal size, when it has a firm consistency and generally when the apex of the calyx has begun to break. Small-fruited varieties, selected for this purpose, undergo cultivation practices similar to those used for the large tomato. For marketing purposes, the small fruit must not fill the calycinal envelope. On the other hand, the large tomato must fill it completely and should preferably break it to reveal part of the fruit (this is visually attractive to the purchaser) (Fig. 21). 5 Individual plants may produce 64-200 fruit in a season. The freshness and greenness of the husk are major quality criteria. 14 Storage The unhusked fresh fruits can be stored in single layers in a cool, dry atmosphere for several months. Mexican and Central American people may pull up the entire plant with fruits attached and hang it upside-down in a dry place until the fruits are needed. 7 Pollination Tomatillo is self-incompatible, so all plants are hybrids. Pollination is by insects. 6 Plant at least two tomatillo plants to achieve proper fertilization for fruit production. 18 Propagation By seeds, established plants can be used to root stem cuttings. 17 Cuttings should root easily. Heavy rains cause the plants to bend down to the ground and it has been observed that tips that touch the soil take root and the new shoots grow vigorously. 7 The greater percentage of dormancy occurs in the seed recently extracted from the fruit. In less than a year it reaches its maximum germination potential, losing it drastically as from the third year under commercial storage conditions. 5 Tomatillo seeds should be sprouted in small containers, preferably 4" or smaller. In-ground germination is not recommended because conditions are not as easily controlled. Use a standard potting mix that is well drained. Make sure potting mix is damp prior to planting the seeds. With very small seeds such as Tomatillo (Fig. 23,24), watering overly dry soil can cause the seeds to dislodge from their position and sink deep into cracks in the soil. Seeds that sink deeply into soil will not be able to reach the soil surface once germinated. 17 Soil should be kept consistently warm, from 70-85 °F. Cool soils, below about 60-65 °F, even just at night, will significantly delay or inhibit germination. Hot soils above 95 °F will also inhibit germination. 17 The seed germinates in 7-10 days, followed by elongation of the primary shoot for 4 weeks. 6 Seed germination to mature fruit usually takes 75 to 100 days for most varieties.

Fig. 23. Tomatillo groundcherry seeds Fig. 24. Tomatillo seeds during a seed quality inspection exercise Planting Transplanting of the tomatillo is widespread, principally in the areas where frosts make it essential. Its advantages include saving on seed, reduced weeding and the possibility of starting the cycle while there is still another crop on the ground as well as shortening the growing cycle. Sowing density ranges from 17000-25000 plants per hectare. Remember to transplant these species deep, up to the first true leaves. Roots will form along the buried portion of the stem, increasing water and nutrient uptake. 15 In South Florida, this species can be planted between August and February as there is no danger of frost. 15 Climate Tomatillo is a warm-season crop, sensitive to freezing tem-peratures at any growth stage. Optimum growth occurs attemperatures above 65 °F (18.3 °C) and growth is poor below 61 °F (16.1 °C). High temperatures during flowering, however, result in poor fruit set. 8 Staking Due to its rapid and branching growth it is recommended to stake them. Staking also facilitates later harvesting and prevents the fruit from touching the ground, which reduces damage to fruit and husk. Staking can also reduce disease, as well as slug damages. 8 Fertilizing Fertilization is recommended at a moderate level. An application of 40-90 kg/ha of phosphorus is common. Depending on soil type and irrigation, other nutrients and fertilzers (N/ K) may be required. 8 Irrigation Even though tomatillo plants becomes more drought tolerant the older they get, regular watering is required. Water can either come from rainfall or irrigation. Irrigation can either be managed by drip, sprinkler, furrow or watering can. Irrigation frequency is depending on weather and crop's growth stage from once or twice a week to daily during hot weather periods. 8 Food Uses The tomatillo has been a constant component of the Mexican and Guatemalan diet up to the present day, chiefly in the form of sauces prepared with its fruit and ground chillies to improve the flavour of meals and stimulate the appetite. The tomatillo is also used in sauces with green chilli, mainly to lessen its hot flavour. The fruit of the tomatillo is used cooked, or even raw, to prepare purees or minced meat dishes which are used as a base for chilli sauces known generically as salsa verde (green sauce). They can be used to accompany prepared dishes or else be used as ingredients in various stews. An infusion of the husks (calyces) is added to tamale dough to improve its spongy consistency, as well as to that of fritters; it is also used to impart flavour to white rice and to tenderize red meats. 5 The fruit is normally cooked before it is consumed. 6

Fig. 32. Chips and salsa. Fig. 33. The huevos rancheros: two fried eggs on blue corn tortillas with frijoles and roast tomato salsa (green tomatillo was also available). Nice and spicy, good stuff. At Wahaca, Charlotte Street, London, UK. Fig. 34. Roasted tomatillo salsa for Cinco de Mayo, New Zealand. Fig. 35. Becker lane farm pork braised in the wood oven with sweet and spicy chiles, Tokyo turnips, and tomatillos. Chez Panisse Cafe, Berkeley, CA. Nutrient Content Tomatillos are an excellent source of vitamins C and K, iron, magnesium, phosphorus and copper. They are a very good source of dietary fiber and are rich in niacin, potassium, and manganese. 18 Medicinal Properties ** It is said in Mexico that a decoction of the calyces will cure diabetes. 7 General Genus name comes from the Greek physa meaning a bladder for the inflated calyx. Specific epithet means with sticky or glutinous fruit. 16 Other Physalis species: Cape Gooseberry, Physalis peruviana Cutleaf Groundcherry, Physalis angulata Coastal Groundcherry, Physalis angustifolia, University of Florida pdf Ground Cherry, Wild Husk Tomatoes, Almost, Eat The Weeds Tomato, Husk, Physalis pruinosa L., University of Florida pdf List of Growers and Vendors |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bibliography 1 "Physalis philadelphica Lam. common names." USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System, Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN-Taxonomy), National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland, 2019, npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?id=102411. Accessed 2 Sept. 2019. 2 "Physalis philadelphica Lam. synonyms." Plants of the World Online, Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:817532-1. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. 3 "Physalis philadelphica Lam." Data sheet, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Ecocrop FAO, ecocrop.fao.org/ecocrop/srv/en/dataSheet?id=8556. Accessed 4 Sept. 2019. 4 "Physalis philadelphica Lam." Ecoport, ecoport.org/ep?Plant=8556&entityType=PLCR**&entityDisplayCategory=full. Accessed 4 Sept. 2019. 5 Hernández, Montes S. and J. R. Aguirre Rivera. "Tomatillo (Physalis philadelphica)." Neglected Crops 1492 from a Different Perspective, FAO Plant Production and Protection Series No. 26, pp. 118-122, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1994, FAO, www.fao.org/docrep/018/t0646e/t0646e.pdf. Accessed 3 Sept. 2019. 6 Moriconi, D. N., et al. "Tomatillo: A Potential Vegetable Crop for Louisiana." Advances in new crops, Edited by J. Janick and J. E. Simon, 1990, NewCROP TM, hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/proceedings1990/V1-337.html. Accessed 14 Sept. 2019. 7 Fruits of Warm Climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, 1987. 8 Smith R., et al. "Tomatillo production in California." Vegetable Production Series, Agriculture and Natural Ressources, University of California, Pub. 7246, 1999, Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomatillo. Accessed 14 Sept. 2019. 9 The Encyclopedia of Fruit & Nuts. Edited by Jules Janick and Robert E. Paull, Cambridge, CABI, 2008. 10 Stephens, James M. "Tomatillo—Physalis ixocarpa Brot. ex Hornem." Horticultural Sciences Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, Original pub. May 1994, Revised Sept. 2015, Reviewed Oct. 2018, HS677, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mv144. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019. 11 "Cape Gooseberry, Physalis peruviana L." California Rare Fruit Growers, crfg.org.pubs/ff/cape-gooseberry.html. Accessed 10 Sept. 2019. 12 "Physalis philadelphica Lam." Flora of Zimbabwe: Cultivated plants, www.zimbabweflora.co.zw/cult/species.php?species_id=150540. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019. 13 "Physalis philadelphica Lam." Flora of China, Vol. 17: 312, eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, Accessed 12 Nov. 2008, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), eol.org/pages/486222/articles#cite_note-21. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019. 14 Duarte, Odilio and Robert E. Pauli. Exotic Fruits and Nuts of the New World. Cambridge, CABI, 2015. 15 "Tomatillos and Husk Tomatoes." Gardening Solutions, UF/IFAS, AskIFAS, gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/edibles/vegetables/tomatillos.html. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. 16 "Physalis ixocarpa." Plant Finder, Missouri Botanical Garden, www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=287199. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. 17 "Tomatillo, Physalis ixocarpa a.k.a. Husk Tomato." Plant Information Database, Trade Winds Fruit, www.tradewindsfruit.com/content/tomatillo.htm. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. 18 "Tomatillos in the Garden." Yard and Garden Extension, Utah State University, extension.usu.edu/yardandgarden/research/tomatillos-in-the-garden. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. Photographs Fig. 1 "Roasted Salsa Verde (Tomatillo Salsa)." The 99 Cent Chef, 18 July 2013, (CC BY 3.0 US), the99centchef.blogspot.com/2013/07/roasted-salsa-verde-tomatillo-salsa.html. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. Fig. 2 Vicente-Rivera, Luis Humberto. "Large-flowered Tomatillo Physalis philadelphica, Villaflores, Chis., México." INaturalist Research-grade, no. 136464329, 25 Sept. 2022, (CC BY-NC 4.0), Image cropped, www.inaturalist.org/observations/136464329. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. Fig. 3 DiTomaso, Joseph M. "Tomatillo groundcherry (Physalis philadelphica) seedling." University of California-Davis, Uploaded 22Dec. 2008, Updated 19 Feb. 2009, no. 5386635, (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), Bugwood.org, www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=5386635. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019. Fig. 4 Horticulturalist RJ. "Tomatillo plant with buds, pubescent stem and serrated leaves noticeable." 30 May 2016, Commons Wikimedia, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomatillo_plant.jpg. Accessed 14 Sept. 2019. Fig. 5 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis philadelphica (Tomatillo), Habit, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i." no. 110822-8259, 22 Aug. 2011, Starr Environmental, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=25077076736. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 11,14,21 Vincentz, Frank. "Tomatillo Physalis philadelphica in a garden in Kluse (Emsland)." 3 Aug. 2018, Commons Wikimedia, (GFDL, CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kluse_-_Physalis_philadelphica_-_Tomatillo_10_ies.jpg. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 6 andrey_belechov. "Tomatillo, Physalis ixocarpa,Tatarstan, Russia." INaturalist Research-grade, no. 65897429, 30 Nov. 2020, (CC BY-NC 4.0), www.inaturalist.org/observations/65897429. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. Fig. 7 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis philadelphica (Tomatillo), Flowers and leaves, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i." no. 110822-8264, 22 Aug. 2011, Starr Environmental, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24807810990. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 8 Navarro, Andrea. "Physalis philadelphica Lam." INaturalist Research-grade Observations, Global Biodiodiversity Information Facility, no. 21747894, 29 Mar. 2019, GBIF, (CC BY-NC 4.0), Image cropped, www.gbif.org/occurrence/2235488897. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019. Fig. 9 Davidse, Gerrit. "Physalis philadelphica Lam. Solitary, nodding, axillary flower." Tropicos Specimen Data, Missouri Botanical Garden, Global Biodiodiversity Information Facility, no. 100642442, GBIF, (CC BY-NC SA 3.0), www.gbif.org/occurrence/1257984597. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019. Fig. 10 Atha, Daniel. "Physalis philadelphica Lam." INaturalist Research-grade Observations, Global Biodiodiversity Information Facility, no. 7406347, 5 Aug. 2017, GBIF, (CC BY-NC 4.0), www.gbif.org/occurrence/1586149663. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019. Fig. 12 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Physalis philadelphica (Tomatillo), Flower, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i." no. 110822-8261, 22 Aug. 2011, Starr Environmental, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=25077080016. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 13 de:Benutzer:Carstor. "Flower of Tomatillo (Physalis ixocarpa)." 19 July 2006, Commons Wikimedia, (CC BY-SA 2.5), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomatillo_flower.jpg. Accessed 14 Sept. 2019. Fig. 15,18 Vincentz, Frank. "Tomatillo Physalis philadelphica in a garden in Kluse (Emsland)." 3 Aug. 2018, Commons Wikimedia, GFDL, (CC BY-SA 3.0), Image cropped, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kluse_-_Physalis_philadelphica_-_Tomatillo_10_ies.jpg. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 16 Smitworks. "Na bestuiving van de bloem vallen de bloemblaadje af en begint te vrucht te groeien." 16 May 2016, Commons Wikimedia, (CC BY 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Starting_Tomatillo_Verde_Flower_after_pollination_maarten_smit_smitworks.jpg. Accessed 14 Sept. 2019. Fig. 17 jmneiva. "Tomatillo, Physalis ixocarpa, Loulé, Portugal." INaturalist Research-grade, no. 60373808, 21 Sept. 2020, (CC BY-NC 4.0), www.inaturalist.org/observations/60373808. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. Fig. 19 Davidse, Gerrit. "Physalis philadelphica Lam. Berry, calyx partially removed." Tropicos Specimen Data, Missouri Botanical Garden, Global Biodiodiversity Information Facility, no. 100642442, GBIF, (CC BY-NC SA 3.0), www.gbif.org/occurrence/1257984597. Accessed 21 Sept. 2019. Fig. 20 Underpraha. "Ripe tomatillo, partially opened." 4 May 2008, Commons Wikimedia, Public Domain, Image cropped, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Physalis_philadelphica_(fruit)#/media/File:TomatilloKitchenCounter.jpg. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 22 mickeysmom. "Large-flowered Tomatillo Physalis philadelphica, Country Club Rd, Borrego Springs, CA." INaturalist Research-grade, no. 103106026, 15 Dec. 2021, (CC BY-NC 4.0), Image cropped, www.inaturalist.org/observations/103106026. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. Fig. 23 Walters, D., and C. Southwick. "Tomatillo groundcherry (Physalis philadelphica) Seeds in various positions." Table Grape Weed Disseminule ID, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org , Uploaded 11Feb. 2012, Updated 21 Feb. 2012, no. 5459850, Bugwood.org, (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=5459850. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019. Fig. 24 Schwartz, Howard F. "Tomatillo groundcherry (Physalis philadelphica), Tomatillo seeds during a seed quality inspection exercise." Colorado State University, Bugwood.org, Uploaded 7 Feb. 2008, Updated 18 June 2008, no. 5364389, Bugwood.org, (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=5364389. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019. Fig. 25 Abrahami. "Physalis ixocarpa fruit." 22 July 2008, Commons Wikimedia, GFDL, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Physalis_ixocarpa.JPG. Accessed 14 Sept. 2019. Fig. 26 Wrightson, Barney. "Purple Tomatillos." Feb. 16, 2012, (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/barney_wrightson/6891481569/in/photostream/. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019. Fig. 27 Diógenes el Filósofo. "Tomatillo, miltomate, tomate verde, tomate de fresadilla, Physalis ixocarpa, solanáceas."19 May 2013, Commons Wikimedia, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomatillo,_miltomate,_tomate_verde,_tomate_de_fresadilla,_Physalis_ixocarpa.JPG. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 28 Holmes, Gerald. "Tomatillo groundcherry (Physalis philadelphica), Healthy plant showing plant architecture and growth habit. August 1998." California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo, Bugwood.org, Uploaded 26 Oct. 2010, Updated 8 Aug. 2013, Bugwood.org, (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=1575441. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019. Fig. 29 Daderot. "Tomatillos in grocery store, Cambridge. Massachusetts, USA." 16 Sept. 2011, (CC0), Commons Wikimedia, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Physalis_philadelphica_(fruit)#/media/File:Tomatillos,_Cambridge,_MA_-_DSC05398.jpg Fig. 30 Martin, Jeffery. "Tomatillos in a box at a grocery store." 5 Jan. 2014, Commons Wikimedia, (CC0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Physalis_philadelphica_(fruit)#/media/File:Tomatillos_in_a_box.jpg. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019. Fig. 31 Pandya, Binjal. "Roasted corn and tomatillos salsa tacos." Binjal’s VEG Kitchen, 20 Feb. 2018, (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), binjalsvegkitchen.com/roasted-corn-tomatillos-salsa-tacos/. Accessed 17 Apr. 2023. Fig. 32 stu_spivack. "Chips and salsa." 24 Mar. 2007, Flickr, (CC BY-SA 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/stuart_spivack/435397512/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019. Fig. 33 Munro, Ewan. "The huevos rancheros: two fried eggs on blue corn tortillas with frijoles and roast tomato salsa (green tomatillo was also available). Nice and spicy, good stuff. At Wahaca, Charlotte Street." 22 Oct. 2012, Flickr, (CC BY-SA 2.0), Image cropped, www.flickr.com/photos/55935853@N00/8112148426/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019. Fig. 34 Herbert, Mairi. "Roasted Tomatillo Salsa for Cinco de Mayo." Toast Blog, 25 May 2011, (CC BY-ND 3.0), Image cropped, www.toast-nz.com/2011/05/roasted-tomatillo-salsa-for-cinco-de.html. Accessed 17 Apr. 2023. Fig. 35 City Foodsters. "Becker lane farm pork braised in the wood oven with sweet and spicy chiles, Tokyo turnips, and tomatillos. Chez Panisse Cafe, Berkeley, CA." 17 Aug. 2013, Flickr, (CC BY 2.0), Image cropped, www.flickr.com/photos/cityfoodsters/9605079410/in/photolist-hRsnWr-gEQz1Z-gEPZ9c-gEPVtN-fCLo8f-fCLxtq-fCtYjH/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019. * UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas ** The information provided above is not intended to be used as a guide for treatment of medical conditions using plants. Published 22 Sept. 2019 LR. Last update 16 Apr. 2023 LR |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||