| Mango - Mangifera indica | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 1 Mangifera indica Mango 'Saber'

Mango fruits – single and halved, grown in Brazil  Fig. 3  M. indica (leaves), Maui, Kula Ace Hardware and Nursery  Fig. 4  New growth on M. indica  Fig. 11  Fig. 12  Close-up of a twig of 'Alphonso' mango tree carrying flowers and immature fruit  Fig. 13   Fig. 14   Fig. 15  M. indica, Playa Esmeralda, Rafael Freyre, Holguin, Cuba  Fig. 22  Indian Mango M. indica, Honduras  Fig. 23  Indian Mango M. indica, Panajachel, Guatemala  Fig. 24  Mango, in moist Brazilian tropics  Fig. 25  Mangifera indica, N Lake Dr, Boynton Beach, FL, US  Fig. 31  Cold protection system at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden  Fig. 32  Mango orchard on Réunion island  Fig. 33   Fig. 34  Large street tree in India  Fig. 35  This is a kind of mango tree seen in Kerala, called naaTTumaav  Fig. 36   Fig. 37  Partially ripened 'Banganpalli' mangoes being sold on a bicycle at Guntur City, India. These are available from the middle of May to June of the summer season.  Fig. 38  Many cultivars of mango, M. indica from West Java, Indonesia. E.g. mangga 'golek', mangga 'gedong' and mangga 'arumanis'.  Fig. 39  Mangoes, as displayed by the seller in front of the Samayapuram Mariyamman Temple at Samayapuram, Tiruchirappalli  Fig. 40   Fig. 41  The raspberry on top gives a nice flavour to the mango cheese cake. Cheers and Happy Eating!  Fig. 42  Mango berry popsicles  Fig. 43  Mango shrimp ceviche  Fig. 54  Mine, the mango is! |

Scientific

name Mangifera indica L. Pronunciation man-JIFF-er-uh IN-dih-kuh 9 Common names English: mango; Cambodia: svaay; Hindi: aam, am, amb; Dutch: bobbie manja, kanjanna manja, maggo, manggaboom, manja; French: mangot, mangue, manguier; German: Mangobaum; Indochina: ma muang; Indonesia: mangga, mempelam; Ilokano: mango; Laos: mwàngx; Malaysia: manga, mempelam, ampelam; Myanmara: tharyetthi; New Guinea, Pidgin: mango; Spanish: mango, manga amarilla, manga blanca, mango de hilacha; Portuguese: mango, mangom, mangueira; Philippines: paho (Bisaya); Southeast Asia: mangga; Thai: mamuang; Tamil; ampleam; Tagalog: mangga; Vietnam: xoài 5,6 Synonyms M. amba Forsk., M. domestica Gaertn., M. gladiata Boj., M. racemosa Boj., M. rubra Boj. 4 Relatives Bindjai (M. caesia), horse mango (M. foetida), Kuweni mango (M. odorata) 2 Distant affinity Cashew (Anacardium occidentale), gandaria (Bouea gandaria), pistachio (Pistacia vera), marula (Sclerocarya birrea), ambarella (Spondias cytherea), yellow mombin (S. mombin), red mombin (S. purpurea), imbu (S. tuberosa) 2 Family Anacardiaceae (sumac/cashew family) Origin Mangos originated in the Indo-Burma region and are indigenous to India and Southeast Asia 1 USDA hardiness zones 10b-12 9 Uses Fruit; shade; landscape specimen; hedge; screen Height 30-100 ft (9.5-30.5 m) 1 Spread May with age, attain 100-125 ft (30-38 m) in width 3 Crown Broad; rounded; symmetrical; dense canopy or a more upright, oval, relatively slender crown 3 Growth rate Fast 24 in. (60 cm) or more per season Longevity Long-lived, some specimens being known to be 300 years old and still fruiting 3 Trunk/bark/branches Multi-branched; branches droop and are susceptible to breakage; not showy; typically one trunk Pruning requirement Needed for strong structure Leaves Evergreen; simple; alternately arranged; lanceolate; 6-16 in. (15-40.6 cm); rich green; leathery; red new growth 1,10 Flowers Showy; pinkish/white; flowers in spring or winter; has either male or female flowers (dioecious); many-branched panicle borne at the ends of shoots; bloom from Dec. to Apr. depending upon climatic conditions and variety Fruit Drupe; nearly round, oval, ovoid-oblong; size/color depends upon variety; skin is smooth, leathery; flesh pale-yellow to deep-orange; single large, flattened, kidney-shaped seed enclosed in a woody husk 1 Season May-Sept. depending on cultivar USDA Nutrient Content pdf Light requirement Full sun 9 Soil tolerances Clay; sand; loam; alkaline; acidic; well-drained 9 pH preference 5.5-7.5 Drought tolerance Moderate 9 Aerosol salt tolerance Moderate 9 Cold tolerance Flowers/small fruit can be killed below 40 ºF (4.4 ºC); mature trees may withstand short periods as low as 25 ºF (-3.9 ºC) 1 Plant spacing Unpruned: 25-30 ft (7.6-9.` m) apart; pruned: 12-15 ft (3.7-4.6 m) 1 Roots Long tap root and dense surface mass of feeding roots 5 Invasive potential * Caution in central and south Florida, manage to prevent escape, may be recommended by IFAS; South: not considered a problem species and may be recommended Pest/Disease resistance Sensitive to pests/diseases; scales followed by sooty mold and Mediterranean fruit fly are pests of this tree; anthracnose on fruit and leaves is a serious problem Known hazard Some people are allergic to the pollen, sap and even the fruit Reading Material Mango Growing in the Florida Home Landscape, University of Florida pdf Growing Mango, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Mangifera indica: Mango, University of Florida pdf Mango, Fruits of Warm Climates The Mango, Manual Of Tropical And Subtropical Fruits Mangifera indica (mango), Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry pdf Mango a New Reality, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Origin Mangos originated in the Indo-Burma region and are indigenous to India and Southeast Asia. 1 Distribution Mangos are grown in tropical and subtropical lowlands throughout the world. In Florida, mangos are grown commercially in Dade, Lee, and Palm Beach Counties and as door yard trees in warm locations along the southeastern and southwestern coastal areas and along the southern shore of Lake Okeechobee. 1 The History of Mangos in South Florida, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Description Mangifera indica is thought to have been in cultivation for so long that its natural distribution has been obscured. Grown in the open, it forms a very dense, round crown of large, leathery, lance-shaped, drooping leaves aver a stout trunk. In late winter and early spring, a flush of new, bright red leaves are borne, followed by tiny, yellow-green to pink fragrant flowers held in erect, red stemmed, showy panicles. The legendary, aromatic, heavy fruit is truly a masterpiece. Almost heart-shaped, dangling on its long, stout stalk, the luminous, ripe fruit is mostly blushed pink, red or purple, with a delicate, iridescent, powdery bloom. 10

Fig. 5. 'Ice Cream' Fig. 6. 'Pickering' Fig. 7. 'Vallenato' fig. 8. 'Mallika' Fig. 9. 'Nan Doc Mai' Fig. 10. 'Julie' Roots The mango has a long taproot that often branches just below ground level, forming between two and four major anchoring taproots tan can reach 6 m (20 ft) down to the water table. The more fibrous finer roots (feeder roots) are found from the surface down to approximately 1 m (3.3 ft) and usually extend just beyound the canoty diameter. Distribution of the finer roots changes seasonall with the moinsture distribution in the soil. 6 Leaves Nearly evergreen, alternate leaves are borne mainly in rosettes at the tips of the branches and numerous twigs from which they droop like ribbons on slender petioles 1 to 4 in (2.5-10 cm) long. The new leaves, appearing periodically and irregularly on a few branches at a time, are yellowish, pink, deep-rose or wine-red, becoming dark-green and glossy above, lighter beneath. The midrib is pale and conspicuous and the many horizontal veins distinct. Full-grown leaves may be 4 to 12.5 in (10-32 cm) long and 3/4 to 2 1/8 in (2-5.4 cm) wide. 3 Leaves may live up to five years. 1 Flowers Hundreds and even as many as 3,000 to 4,000 small, yellowish or reddish flowers, 25 to 98 % male, the rest hermaphroditic, are borne in profuse, showy, erect, pyramidal, branched clusters 2 1/2 to 15 1/2 in (6-40 cm) high. 3 Inflorescense Sequence

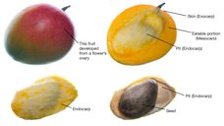

Fruit There is great variation in the form, size, color and quality of the fruits. They may be nearly round, oval, ovoid-oblong, or somewhat kidney-shaped, often with a break at the apex, and are usually more or less lop-sided. They range from 2 1/2 to 10 in (6.25-25 cm) in length and from a few ounces to 4 to 5 lbs (1.8-2.26 kg). The skin is leathery, waxy, smooth, fairly thick, aromatic and ranges from light-or dark-green to clear yellow, yellow-orange, yellow and reddish-pink, or more or less blushed with bright-or dark-red or purple-red, with fine yellow, greenish or reddish dots, and thin or thick whitish, gray or purplish bloom, when fully ripe. Some have a "turpentine" odor and flavor, while others are richly and pleasantly fragrant. The flesh ranges from pale-yellow to deep-orange. It is essentially peach-like but much more fibrous, extremely juicy, with a flavor range from very sweet to subacid to tart. 3

Fig. 26. Seed inside a woody husk Fig. 27. Parts of a mango (Mangifera indica) fruit Seed Types Mango varieties produce either monoembryonic or polyembryonic seeds. Polyembryonic seeds contain more than one embryo and most of the embryos are genetically identical to the mother tree. Monoembryonic seeds contain one embryo and this embryo possesses genes from both parents. A tree planted from a polyembryonic seed will be identical to its parent tree, whereas a tree planted from a monoembryonic seed will be a hybrid (mix of both parents). 1 Florida monoembryonic cultivars: 'Tommy Atkins', 'Keitt', 'Kent', 'Van Dyke', 'Palmer', 'Irvin' and 'Glenn'. 8 Florida polyembryonic cultivars: 'Florigon', 'Saigon', Nom Doc Mai' and 'Okrung'. 8 Varieties Indian Types typically have monoembryonic seeds and often highly colored fruit. The fruit tend to be more susceptible to anthracnose and internal breakdown. Most commercial Florida varieties are of this type.1 Indochinese Types typically have polyembryonic seeds and fruit often lack attractive coloration (i.e., they are green, light green, or yellow). The fruit tend to be relatively resistant to anthracnose. Florida varieties of this group are not commercially important, although some are appreciated in home plantings. 1 In many areas of the tropics, there are seedling mangos which do not clearly fit in either of these types. Some of these are ‘Turpentine’, ‘Number 11’, ‘Madame Francis’, and ‘Kensington’. There are many mango varieties available in south Florida and many are appropriate for small and large home landscapes. Some characteristics of the most important Florida varieties are summarized in Table 1. 1 Mango Varieties Mango Varieties Recommended for Florida, University of Florida The Mangos of Fairchild Evolution, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Green Thai Mangos, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Many Choices Now for Your Back Yard Mango Tree, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Uncommon Mangos, Edible South Florida Taming the wild mango, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Harvesting Mango fruits will ripen on the tree, but, are usually picked when firm and mature (Table 1). Table 1 may be used as a guide to when picking your fruit may begin. However, slight year-to-year variations occur in when maturity begins. The crop is considered mature when the shoulders and the nose (the end of the fruit away from the stem) of the fruit broaden (fill out). Varieties that have color when ripe may have a slight blush of color development, or they may have begun to change color from green to yellow. Prior to this peel color break, the fruit is considered mature when the flesh near the seed changes color from white to yellow. 1 The fruit from mango trees do not all have to be harvested at the same time. This feature allows you to leave the fruit on the tree and pick fruit only when you want to eat it. Remember, it takes several days or more (depending upon how mature the fruit is) for the fruit to ripen once it is picked. As the season of harvest for any given variety passes, the fruit continue to mature (and later ripen) and there is an increased chance the fruit will begin to fall from the tree. 1 The period of development from flowering to fruit maturity is 100 to 150 days. 1 Harvest Calendar Pollination In Florida, mangos bloom from December to April depending upon climatic conditions and variety. 1 Mango flowers are visited by fruit bats, flies, wasps, wild bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, ants and various bugs seeking the nectar and some transfer the pollen but a certain amount of self-pollination also occurs. Honeybees do not especially favor mango flowers. 3 Propagation Mango trees may be propagated by seed and vegetatively. Vegetative propagation is necessary for monoembryonic seed types, whereas varieties with polyembryonic seeds come true from seed. 1 There is a single, longitudinally ribbed, pale yellowish-white, somewhat woody stone, flattened, oval or kidney-shaped, sometimes rather elongated. Within the stone is the starchy seed, monoembryonic - usually single-sprouting or polyembryonic - usually producing more than one seedling. 3 Veneer-grafting and chip-budding are the most common and successful methods in Florida. Grafted trees will begin to bear 3 to 5 years after planting. Most mango varieties are grafted onto polyembryonic rootstocks. Common polyembryonic rootstocks include ‘Turpentine’ and unnamed criollo-types. These rootstocks are tolerant of high pH soils and seedlings are vigorous and relatively uniform. 1 Mangoes - Polyembryonic, Sub-Tropical Fruit Club of Qld Mango Propagation, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Graft-induced Off-season Flowering and Fruiting in the Mango, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia The inverted root graft: applications for the home garden in Florida, Fla. State Hort. Soc. pdf Top Working of Mango Trees, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Grafting Mangos, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Pruning Formative pruning of young trees may be advantageous because it by increases the number of lateral branches and establishes a strong framework for subsequent fruit production. After several years of production, it is desirable to cut back the tops of trees allowed to grow to 12 to 15 feet (3.7-4.6 m). 1 Training and Pruning a Mango Orchard to Improve Blooming, Architecture and Yield in South Florida, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden pdf Pruning Mango Trees: Two Main Precautions Before you Begin, University of Florida, Lee County pdf Response to Severe Pruning, University of Florida, Lee County pdf Fertilizing In Florida, young trees should receive fertilizer applications every month during the first year, beginning with 1/4 lb (114 g) and gradually increasing to one pound (455 g). Thereafter, 3 to 4 applications per year in amounts proportionate to the increasing size of the tree are sufficient. For bearing trees, nitrogen should be drastically reduced or eliminated, and potash should be increased to 9 to 15%, and available phosphoric acid reduced to 2 to 4%. Examples of commonly available fertilizer mixes include 6-6-6-2 [6 (N)-6 (P2O5)-6 (K2O)-2 (Mg)], 6-3-16 and 0-0-22. Little to no nitrogen is needed for mature healthy trees; in contrast emphasize potash and minor element nutrition. 1 Mango: Calcium – a key for good Mango yield and quality, Sub-tropical Fruit Club of Qld Nutrient Deficiencies Leaf tip burn may be a sign of excess chlorides. Manganese deficiency is indicated by paleness and limpness of foliage followed by yellowing, with distinct green veins and midrib, fine brown spots and browning of leaf tips. Inadequate zinc is evident in less noticeable paleness of foliage, distortion of new shoots, small leaves, necrosis, and stunting of the tree and its roots. In boron deficiency, there is reduced size and distortion of new leaves and browning of the midrib. Copper deficiency is seen in paleness of foliage and severe tip-bum with gray-brown patches on old leaves; abnormally large leaves; also die-back of terminal shoots; sometimes gummosis of twigs and branches. Magnesium is needed when young trees are stunted and pale, new leaves have yellow-white areas between the main veins and prominent yellow specks on both sides of the midrib. There may also be browning of the leaf tips and margins. Lack of iron produces chlorosis in young trees. 3 Irrigation Newly planted mango trees should be watered at planting and every other day for the first week or so, and then 1 to 2 times a week for the first couple of months. During prolonged dry periods (e.g., 5 or more days of little to no rainfall) newly planted and young mango trees (first 3 years) should be watered once a week. Once the rainy season arrives, irrigation frequency may be reduced or stopped. 1 Once mango trees are 4 or more years old, irrigation will be beneficial to plant growth and crop yields only during very prolonged dry periods during spring and summer. 1 Common Questions Concerning Young Mango Trees, University of Florida, Miami-Dade Extension pdf Pests Many insect pests attack mangos, but they seldom limit fruit production significantly. Insect infestations are not predictable and control measures are justified only when large infestations occur. Homeowners should contact their local UF/IFAS Extension office for recommended control measures. 1 Mango Pests and Beneficial Insects, University of Florida pdf Disease/Disorders Page The two major disease problems for mango trees in the home landscape are powdery mildew and anthracnose. Both these fungal pathogens attack newly emerging panicles, flowers, and young fruit. One to two early spring applications of sulfur and copper timed to begin when the panicle is 1/4 full size and then 10 to 21 days later will greatly improve the chances for fruit set and production. 1 Fruit Protection

Fig. 28. Protection of fruit with 2 liter 'Pop' bottles Fig. 29. Mangoes in paper bags to prevent insect infestation Fig. 30. Wire cages to protect your fruit from squirrels and other varmints Bagging: Protecting Your Fruit, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Food Uses Some seedling mangos are so fibrous that they cannot be sliced; instead, they are massaged, the stem-end is cut off, and the juice squeezed from the fruit into the mouth. 3 Mangos are predominantly grown for their fruit, which is mostly eaten ripe as a dessert fruit. Mature green mangos are also eaten fresh or as pickles. Fresh mangos are processed and preserved into a wide range of products including pulps, juices, frozen slices, dried slices, pulp (fruit leather), chutneys, jams, pickles, canned in syrup, and sliced in brine. 6 Mango purees and essences are used to flavor many food products such as drinks, ice creams, wines, teas, breakfast cereals, muesli bars, and biscuits. 6 Recipes, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Virtual Herbarium Preserving Mangos: Freezing and Drying, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden How to Eat Mangos Mango Fork, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia South Florida Tropicals: Mango, University of Florida pdf (archived)

Fig. 44. Mango chutney Fig. 45. Mango iced tea Fig. 46. No bake eggless mango cheesecake Fig. 47. Mango martini Fig. 48. Unripe mango (bn: Aam) chutney, it is a very popular dish in West Bengal Fig. 49. Philippine mangoes in town! (The "hedgehog" style is a form of mango preparation) Fig. 51. "Amba vadi", a term in marathi denotes this foodstuff made up of mango juice; Amba vadi is prepared by drying mango juice in sun; Mmngoes are seasonal fruits and in order to enjoy them yearlong, amba vadis are made; mango juice is poured into a plate and left to dry in scorching heat of India, result: a roti of mango juice that can be preserved and tastes like mango juice Fig. 52. India, mango sun-drying for pickle making Fig. 53. Mango fork: most people enjoy eating the residual flesh from the seed and this is done most neatly by piercing the stem-end of the seed with the long central tine of a mango fork, commonly sold in Mexico, and holding the seed upright like a lollypop 3 Fresh-Cut Mango Best Management Practices Manual, University of Florida pdf Medicinal Properties ** Dried mango flowers, containing 15% tannin, serve as astringents in cases of diarrhea, chronic dysentery, catarrh of the bladder and chronic urethritis resulting from gonorrhea. The bark contains mangiferine and is astringent and employed against rheumatism and diphtheria in India. The resinous gum from the trunk is applied on cracks in the skin of the feet and on scabies, and is believed helpful in cases of syphilis. 3 Mango kernel decoction and powder (not tannin-free) are used as vermifuges and as astringents in diarrhea, hemorrhages and bleeding hemorrhoids. The fat is administered in cases of stomatitis. Extracts of unripe fruits and of bark, stems and leaves have shown antibiotic activity. In some of the islands of the Caribbean, the leaf decoction is taken as a remedy for diarrhea, fever, chest complaints, diabetes, hypertension and other ills. A combined decoction of mango and other leaves is taken after childbirth. 3 Other Uses The bark possesses 16% to 20% tannin and has been employed for tanning hides. It yields a yellow dye, or, with turmeric and lime, a bright rose-pink. 3 A somewhat resinous, red-brown gum from the trunk is used for mending crockery in tropical Africa. In India, it is sold as a substitute for gum arabic. 3 Having high stearic acid content, the fat is desirable for soap-making. The seed residue after fat extraction is usable for cattle feed and soil enrichment. 3 An important honey plant. 10 Toxicity The sap which exudes from the stalk close to the base of the fruit is somewhat milky at first, also yellowish-resinous. It becomes pale-yellow and translucent when dried. It contains mangiferen, resinous acid, mangiferic acid, and the resinol, mangiferol. It, like the sap of the trunk and branches and the skin of the unripe fruit, is a potent skin irritant, and capable of blistering the skin of the normal individual. As with poison ivy, there is typically a delayed reaction. Hypersensitive persons may react with considerable swelling of the eyelids, the face, and other parts of the body. 3 When mango trees are in bloom, it is not uncommon for people to suffer itching around the eyes, facial swelling and respiratory difficulty, even though there is no airborne pollen. The few pollen grains are large and they tend to adhere to each other even in dry weather. The stigma is small and not designed to catch windborne pollen. The irritant is probably the vaporized essential oil of the flowers which contains the sesquiterpene alcohol, mangiferol, and the ketone, mangiferone. 3 Mango wood should never be used in fireplaces or for cooking fuel, as its smoke is highly irritant. 3 Condo Mangos - The term “condo mango” was coined by Dr. Richard Campbell, Ph.D. the curator of tropical fruit a Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden in Coral Gables, Florida. It refers to varieties that are conducive to container growing, thus are small by nature and can be kept even smaller through selective pruning. Condo mangos are suitable for balconies, greenhouses, or for planting in suburban backyards. By cutting the tips of the branches once or twice a year the trees can easily be maintained at six to ten feet according to variety. Training the tree to stay small is very easy, and the fruits of your labor are sure to impress. 7 General M. indica has been recorded and cultivated in India for over 4,000 years and is revered by Buddhists and Hindus,who use its leaves as decoration at weddings in the hope that the couple will give birth to a son. 10

Fig. 55. Mango distribution map, wild populations Further Reading Mango Articles, Florida State Horticultural Society Mango, California Rare Fruit Growers Mango Plant Guide, National Institute of Food and Agriculture USDA pdf Mango, manako, Common Forest Trees of Hawaii, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa pdf Mango, Mangifera indica, Fruitipedia Mango Culture - Far North Queensland, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Mango Culture in Malaysia, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Do 'Mango Winds' Cause Fruit Drop? Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Mango Postharvest Best management Practices Manual, University of Florida pdf National Mango Board Ext. link Mango Botanical Art List of Growers and Vendors |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bibliography 1 Crane, Jonathan H., et al. "Mango Growing in the Florida Home Landscape." Horticultural Sciences Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, Original pub. Apr. 1994, Revised May 2003, May 2017, and Mar. 2020, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg216. Accessed 10 Jan. 2018, 8 Aug. 2020. 2 "Mango." California Rare Fruit Growers, 1996, crfg.org. Accessed 17 Feb. 2015. 3 Fruits of Warm Climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, 1987. 4 Fern, Ken. "Mangifera indica L." Useful Tropical Plants Database, tropical.theferns.info.com. Accessed 26 Mar. 2016. 5 "Mangifera indica, Mango." Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, cabi.org. Accessed 26 Mar. 2016. 6 Bally, Ian S. E. "Mangifera indica, Mango." Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry, Apr. 2006, traditionaltree.org. Accessed 28 Mar. 2016. 7 "Mango Variety Viewer, Condo Mangos." Top Tropicals, toptropicals.com. Accessed 28 Mar. 2016. 8 Beckford, Roy. Some Additional Information on Mango. Presentation, University of Florida, Lee County. 9 Gilman, Edward, F., et al. "Mangifera indica: Mango." Environmental Horticulture Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, NH563, Original pub. Nov. 1993, Revised Dec.2018, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/ST404. Accessed 4 july 2023. 10 Barwick, Margaret. Tropical & Subtropical Trees. A Worldwide Encyclopaedic Guide. London, 2004. Photographs Fig. 1 Maguire, Ian. "Mango 'Saber'." Tropical Fruit Photography Picture Archive, 2000, trec.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 28 Mar. 2016. Fig. 2 Leidus, Ivar. "Mango fruits – single and halved. Grown in Brazil." Wikimedia Commons,28 Jan. 2022, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.orgwiki/File:Mangos_-_single_and_halved.jpg. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 3 Starr, Forest, and Kim. "Mangifera indica, Mango, manako, meneke (leaves). Location: Maui, Kula Ace Hardware and Nursery." Starr Environmental, no. 070906-8526, 6 Sept. 2007, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24865239356. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 4 Valke, Dinesh. "Mangifera indica." Wikimedia Commons, via Flickr, 6 May 2007, (CC BY-SA 2.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mangifera_indica_(486463993).jpg. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 5,31 Jackson, Karen. "Mango series." 2014, www.growables.org. Fig. 6,8,9,14,28 Robitaille, Liette. "Mango series." 2014, www.growables.org. Fig. 7 "Mangifera indica 'Vallenato'." Top Tropicals, toptropicals.com. Accessed 15 Feb. 2015. Fig. 10 Sample, Jane. "Mango 'Julie'." Flickr, 2012, flickr.com. Accessed 28 Mar. 2016. Fig. 11,16,17,18,19,20,21 Maguire, Ian. "Mango Inflorescence Sequence." Tropical Fruit Photography Picture Archive, 2000, trec.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 28 Mar. 2016. Fig. 12 Kulkarni, Ram. "Close-up of a twig of Alphonso mango tree carrying flowers and immature fruit. The photo was taken at Deogad (or Devgad), Maharashtra, India." Wikimedia Commons, 10 Feb. 2010, GFDL, commons.wikimedia.orgwiki/File:MangoImmatureFruits.JPG. Accessed 27 Mar. 2016. Fig. 13 Raviteja29123. "Insects." Wikimedia Commons, 25 June 2017,(CC BY-NC 4.0) commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Insects_on_mango_tree.jpg. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 15 Reichl, Oliver K. "Indian Mango Mangifera indica, Playa Esmeralda, Rafael Freyre, Holguin, Cuba." iNaturalist, Research Grade, no. 5218811, 3 Mar. 2017, (CC BY-NC 4.0), www.inaturalist.org/observations/5218811. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 22 Mayra. "Indian Mango Mangifera indica, Honduras." iNaturalist, Research Grade, no. 123694194, 27 June 2022,(CC BY-NC 4.0), www.inaturalist.org/observations/123694194. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 23 Kaufman, Dave. "Indian Mango Mangifera indica, Panajachel, Guatemala." iNaturalist, Research Grade, no. 162211706, 17 May 2023, (CC BY-NC 4.0), www.inaturalist.org/observations/162211706. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 24 Chris.urs-o - Marinho, Maria. "Mango, in moist Brazilian tropics." Wikimedia Commons, 2009, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 27 Mar. 2016. Fig. 25 spiker. "Indian Mango Mangifera indica, N Lake Dr, Boynton Beach, FL, US." iNaturalist, Research Grade, no. 169089363, 23 June 2023 , (CC BY-NC 4.0), www.inaturalist.org/observations/169089363. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 26 An.ha. "The inside of a mango (Mangifera indica) pit." Wikimedia Commons, 28 Jan. 2022,(CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.orgwiki/File:Mangifera_indica_pit.jpg. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 27 DutraElliott. "Example of a drupe: parts of a mango (Mangifera indica) fruit." Flickr, 27 July 2021, (CC BY-NC 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/193563217@N04/51339995156/in/dateposted/. Accessed 7 July 2023. Fig. 29 Koo, Malcolm. "Mangoes in paper bags to prevent insect infestation." Wikimedia Commons, 18 July 2021,(CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/File:Mangoes_in_paper_bags.jpg. Accessed 28 Mar. 2016. Fig. 30 Lin, Ed. "How to Protect Your Fruits and Nuts from Squirrels and Other Varmints." Suncoast Tropical Fruit and Vegetable Club. Fig. 32 navez, B. "Mango orchard on Réunion island." Useful Tropical Plants Database, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), tropical.theferns.info.com. Accessed 26 Mar. 2016. Fig. 33,36 Ritter, M., et al. "Mangifera indica Tree Record." Urban Forest Ecosystems Institute, 1995-2016, SelecTree, selectree.calpoly.edu. Accessed 26 Mar. 2016. Fig. 34 "Large tree in India." Useful Tropical Plants Database, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), tropical.theferns.info.com. Accessed 26 Mar. 2016. Fig. 35 Vinayaraj. "This is a kind of Mango tree seen in Kerala, called naaTTumaav." Wikimedia Commons, 2011, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 27 Mar. 2016. Fig. 37 Gnt at en.wikipedia. "Partially ripened Banganpalli mangoes being sold on a Bicycle at Guntur City, India." Wikimedia Commons, 2010, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 30 Mar. 2016. Fig. 38 Djatmiko, W.A. "Many cultivars of mango, Mangifera indica from West Java, Indonesia. E.g. mangga golek, mangga gedong and mangga arumanis." Wikimedia Commons, 2007, GFDL, commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 27 Mar. 2016. Fig. 39 TRYPPN. "Mangoes, as displayed by the seller in front of the Samayapuram Mariyamman Temple at Samayapuram, Tiruchirappalli." Wikimedia Commons, 2010, commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 27 Mar. 2016. Fig. 40 കാക്കര. "Fruit display." Wikimedia Commons,(CC BY-SA 2.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 8 Apr. 2016. Fig. 41 Poddar, Kirti. "Look at the raspberry at the top, gives a nice flavour to the mango cheese cake. Cheers and Happy Eating!" Wikimedia Commons, 2008, (CC BY-SA 2.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 27 Mar. 2016. Fig. 42 Pandya, Binjal. "Mango berry popsicles." Binjal's Veg Kitchen, 7 June 2019,(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), binjalsvegkitchen.com/mango-berry-popsicles/. Accessed 4 July 2023. Fig. 43 Mathur, Neha. "Mango Shrimp Ceviche." Wisk Affair, 12 May 2023, www.whiskaffair.com/mango-shrimp-ceviche-recipe/. Accessed 4 July 2023. Fig. 44 Ganguly, Biswarup. "Unripe mango (bn: Aam) chutney, it is a very popular dish in West Bengal." Wikimedia Commons, 2011, GFDL, commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 27 Mar. 2016. Fig. 45 Pandya, Binjal. "Mango iced tea." Binjal's Veg Kitchen, 14 Apr. 2022,(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), binjalsvegkitchen.com/mango-iced-tea/. Accessed 4 July 2023. Fig. 46 Pandya, Binjal. "No bake eggless mango cheesecake." Binjal's Veg Kitchen, 1 June 2016,(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), binjalsvegkitchen.com/no-bake-eggless-mango-cheesecake/. Accessed 4 July 2023. Fig. 47 Mathur, Neha. "Mango martini." Wisk Affair, 7 May 2021, www.whiskaffair.com/mango-martini-recipe/. Accessed 4 July 2023. Fig. 48 Ballesteros, Nick. "Philippine mangoes in town!" adobongblog, 22 Oct. 2012, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 NZ), www.adobongblog.com/2012_10_01_archive.html. Accessed 4 July 2023. Fig. 49 Luisfi. "Mango." Wikimedia Commons, 2014, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 8 Apr. 2016. Fig. 50 Fruits of Warm Climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, 1987. Fig. 51 Sarangbombatkar. "Amba vadi." Wikimedia Commons, 2015, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 8 Apr. 2016. Fig. 52 Law, Simon. "Mango Chutneys." Wikimedia Commons, Modified by user Mike Hayes,16 Sept. 2006, (CC BY-SA 2.0), commons.wikimedia.orgwiki/File:Mango_Chutney.jpg. Accessed 6 July 2023. Fig. 53 Savage, McKay. "Sights & Culture. Mango sun-drying for pickle making. India." Wikimedia Commons, (CC BY-SA 2.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 8 Apr. 2016. Fig. 54 Milhan, Hash. "Mine, the mango is." Flickr, 24 Apr. 2008, (CC 2.0), Image cropped, www.flickr.com/photos/hashir/2438014969. Accessed 7 July 2023. Fig. 55 Wunderlin, R. P., et al. "Mangifera indica." Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute, 2020, Atlas of Florida Plants, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=1477. Accessed 7 July 2023. * UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas ** Information provided is not intended to be used as a guide for treatment of medical conditions. Published 16 June 2014 LR. Last update 27 Apr. 2024 LR |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||