| Mango Diseases and Disorders | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back

to Mango Page Fig. 1 Anthracnose on fruit, circular and 'tear stain' lesions  Fig. 2 Anthracnose on very young fruit  Fig. 16 Symptoms on stem and panicle  Fig. 17 Powdery mildew symptoms: leaf spots, blight, curling and distortion  Fig. 22 Alga leaf spot caused by Cephaleuros virescens Fig. 25 Gray leaf spot (fungus, Pestalotiopsis mangiferae = Pestalotia mangiferae) Fig. 26 Mango decline, stem gummosis  Fig. 35 Over-irrigation of mango commonly results in basal stem rot in Hawai'i. Move irrigation emitters progressively farther from stems over time.

|

Disease

control for mango tress in the home landscape is usually not warranted

or should not be intensive. The easiest method for avoiding disease

problems is to grow anthracnose-resistant varieties, plant trees in

full sun where the flowers, leaves, and fruit dry off quickly after

rainfall, not to apply irrigation water to the foliage, flowers, and

fruit, and to monitor the tree for disease problems during the

flowering and fruiting season. 1 The two major disease problems for mango trees in the home landscape are powdery mildew and anthracnose. Both these fungal pathogens attack newly emerging panicles, flowers, and young fruit. One to two early spring applications of sulfur and copper timed to begin when the panicle is 1/2 full size and then 10 to 21 days later will greatly improve the chances for fruit set and production. Usually, protecting the panicles of flowers during development and fruit set results in good fruit production in the home landscape. 1 Homeowners should contact their local UF/IFAS Extension office for recommended control recommendations for the diseases discussed below. Anthracnose (Fig. 1,2) Caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Anthracnose can occur on all parts of the mango tree. Leaf infection starts as small, dark, angular to irregular spots. These often coalesce to form large necrotic areas, which may crack. Infections on the flower panicle appear as small brown or black spots which enlarge and often coalesce to cause the death of flowers. Small fruit are rapidly invaded by the fungus once they become infected. On nearly mature or ripe fruit, black spots coalesce to cover large areas, which may be sunken. Surface "tear staining," a phenomenon caused by spores falling from an inoculum source above the fruit, may be apparent. 2

Fig. 3,4,5,6. Anthracnose on fruit circular lesions Fig. 7. On mature fruits “tear stain” lesions Fig. 8. Anthracnose “tear stain” lesions cracking Fig. 9,10,11. Anthracnose symptoms on leaves Fig. 12,13,14. Symptoms on inflorescence and panicles Fig. 15. Symptoms on stem Further Reading Mango Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides), University of Hawai'i at Mānoa pdf Anthracnose of mango: Management of the most important pre‐ and post‐harvest disease, University of Florida TREC pdf Powdery Mildew (Fig. 17) Caused by the fungus Oidium mangiferae In severe attacks, the entire blossom panicle may be involved and fruit fail to set. Infected flowers, flower stalks, and young fruit become coated with the whitish powdery growth of the pathogen and the flowers and young infected fruits are similarly coated with the white fungal growth. Younger leaves may become distorted. On older leaves and fruit, infected tissue has a purplish-brown cast, as the white growth weathers away. The infection on fruit may also appear as an irregular blotch. Affected fruit may turn brown and fall off the tree. The disease is a particular problem in cool dry years. 2

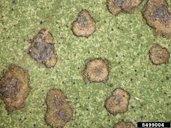

Fig. 18. Fungal mycelium and spores on leaf surface Fig. 19,20,21. Mildew on flowers, panicles and fruit Further Reading Mango Powdery Mildew, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa pdf Mango Scab Caused by Elsinoe mangiferae Scab is a pathogen of young leaves and colonization is favored in cool, wet conditions. Signs of scab on leaves are small spots on the underside of leaves, which turn from dark-brown to gray. Leaves may become distorted and twisted if the infestation is heavy. Gray lesions on twigs may also be apparent. Fruit develops irregular, gray lesions which enlarge as it matures. The lesion centers become corky and cracked, and often exhibit the velvety growth of the fungus in moist weather. 2 Alga Leaf Spot (Fig. 22) Caused by Cephaleuros virescens This alga commences colonization late in the summer and progresses through the winter months. Initially hard to visualize, green, yellow-green, or rust colored leaf spots up to 5 mm in size become raised and roughly circular. Stems may develop cankers where infestation is high. The alga eventually produces rust-colored "spores." These will give rise to more algae if not controlled with copper sprays. 2

Fig. 23,24. Green alga (Cephaleuros virescens) on citrus Further Reading Cephaleuros Species, the Plant-Parasitic Green Algae, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa pdf Verticillium Wilt Caused by Verticillium albo-atrum Verticillium wilt may occur in the limestone soils of Miami-Dade County and is usually observed in new trees planted on land previously used for vegetable production (especially tomatoes). This fungus attacks the tree roots and vascular (water-conducting) system, decreasing and blocking water movement into the tree. Symptoms of infection include leaf wilting, desiccation and browning, stem and limb dieback, and browning of the vascular tissues. Occasionally verticillium will kill young trees. Control consists of removing affected tree limbs by pruning. 1 Leaf Spot (Fig. 25) Caused by Pestalotiopsis mangiferae and Phyllosticta anacardeacearum Both of these fungi cause leaf spot in mango, but with slightly different appearances. P. mangiferae spots are gray and irregularly shaped. They may range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. P. anacardeacearum leaf spots are bleached to white in color and can be numerous on leaves. Both fungi form black dot-like reproductive structures in the lesion centers. 2 Disorders Mango Decline (Fig. 26) (presumably caused by endophytic fungus or fungi) Research to date suggests that mango decline is caused by deficiencies of manganese and iron. These deficiencies may predispose trees to infection by fungal pathogens (Botryosphaeria ribis and Physalospora sp.), which attack shoots, or by root feeding nematodes (Hemicriconemoides mangiferae). Leaf symptoms include interveinal chlorosis, stunting, terminal and marginal necrosis, and retention of dead leaves that gradually drop. Dieback of young stems and limbs is common and even tree death may occur. Increased applications of iron, manganese, and zinc micronutrients have been observed to reduce or ameliorate this problem. 1

Fig. 27,28. Stem gummosis Fig. 29. Internal stem necrosis Fig. 30. Fruit splitting and bleeding Fig. 31. Internal fruit dry rot Fig. 32. Fruit mummification Fig. 33,34. Trunk splitting Further Reading A Reexamination of Mango Decline in Florida, University of Florida TREC pdf Mineral Treatment for Mango Decline, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Internal Breakdown This is a fruit problem of unknown cause, which is also called jelly seed and soft nose. Generally, it is less of a problem on the calcareous (limestone) soils found in south Miami-Dade County and more common on acid sandy soils with low calcium content. The degree of severity may vary from one season to another. Several symptoms may appear including a softening (breakdown) and water soaking of the fruit flesh at the distal end while the flesh around the shoulders remains unripe, an open cavity in the pulp at the stem end, over-ripe flesh next to the seed surrounded by relatively firm flesh, or areas of varying size in the flesh appearing spongy with a grayish-black color. This disorder is aggravated by over fertilization with nitrogen. If fruit have this problem, reduce the rate of nitrogen. In sandy and low- pH soils, increased calcium fertilization may help alleviate this problem. Fruits harvested mature-green are less affected than those allowed to ripen on the tree. 1 Mango Malformation Cused by Fusarium mangiferae Symptoms include the drastic shortening of panicles, giving them a clustered appearance and/or a shortening of shoot internodes. Affected panicles do not set fruit and eventually dry up and turn black. This disorder is not common in Florida, but homeowners should watch for it and immediately prune off affected flower panicles and shoots and destroy them. 3 Further Reading Dooryard Disease Control for Mangos in Florida, University of Florida Miami-Dade, County Extension pdf |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bibliography 1 Crane, Jonathan H., et al. "Mangos Growing in the Florida Home Landscape." Horticultural Sciences Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, Original pub. Apr. 1994, Revised May 2003, May 2017, and Mar. 2020, AskIFAS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg216. Accessed 10 Jan. 2018, 1 Sept. 2020. 2 Mossler, Mark A., and Jonathan Crane. "Florida Crop/Pest Management Profile: Mango." Horticultural Sciences Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, CIR 1401, Pub. Mar. 2002, Reviewed July 2013, AskIFAS, Archived, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 23 june 2014. 3 Bally, Ian S. E. "Mangifera indica, Mango." Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry, Apr. 2006, traditionaltree.org. Accessed 13 July 2023. Photographs Fig. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Nelson, Scot C. "Anthracnose, Colletotrichum gloesporioides." Hawai'i Plant Diseases, hawaiiplantdisease.net. Accessed 22 June 2014. Fig. 17,18,19,20,21 Nelson, Scot C. "Powdery Mildew, Oidium mangiferae." hawaiiplantdisease.net. Accessed 22 June 2014. Fig. 25 Nelson, Scot C. "Grey Leaf Spot, Pestalotia mangiferae." Hawai'i Plant Diseases, hawaiiplantdisease.net. Accessed 22 June 2014. Fig. 22 Shen, Yuan-Min. "Algal spots on the mango leaf." Taichung District Agricultural Research and Extension Station, 2013, Bugwood.org, (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), bugwood.org. Accessed 25 Mar. 2016. Fig. 23,24 Calderon, Cesar. "Green Alga Cephaleuros virescens Kunze." USDA, APHIS, PPQ, 2013, Bugwood.org, (CC BY-NC 3.0 US), bugwood.org. Accessed 25 Mar. 2016. Fig. 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 Nelson, Scot C. "Mango Decline." Hawai'i Plant Diseases, hawaiiplantdisease.net. Accessed 22 June 2014. Fig. 35 Nelson, Scot C. "Irrigation damage." Hawai'i Plant Diseases, hawaiiplantdisease.net. Accessed 25 Mar. 2016. Published 24 June 2014 LR. Last update 3 Jan. 2024 LR |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||